- Home

- Dan Abnett

First and Only Page 16

First and Only Read online

Page 16

'I also want the entire deck searched for hidden vox-relays and vista-lines. Hasker, Varl… use any men you know with technical aptitude to perform the sweep. They may be trying all manner of ways of spying on us. From this moment on, trust no one outside our regiment. No one. There is no way of telling who might be part of the conspiracy around us.'

The officers seemed eager but unsettled. Gaunt knew that this was strange work for regular soldiers. They filed out, faces grave.

Gaunt looked at the crystal in his hand. What are you hiding? he wondered.

SEVEN

Gaunt returned to his quarters with the silent Milo in tow. Corbec had set two Ghosts to guard the commissar's private room. Gaunt sat at the cogitator set into a wall alcove, and began to explore the shipboard information he could access through the terminal. Lines of gently flickering amber text scrolled across the dark vista-plate. He was hoping for a personnel manifest, searching for names that might hint at the identity of those that opposed him. But the details were jumbled and incomplete. It wasn't even clear which other regiments were actually aboard. The Patricians were listed, and a complement of mechanised units from the Bovanian Ninth. But Gaunt knew there must be at least two other regimental strengths aboard, and the listing was blank. He also tried to view the particulars of the Absalom's officer cadre, and any other senior Imperial servants making the crossing with them, but those levels of data were locked by naval cipher veils, and Gaunt did not have the authority to penetrate them.

Technology, such as it was, was a sandbagged barricade keeping him out. He sat back in his chair and sighed. His shoulder was sore. The crystal lay on the console near his hand. It was time to try it. Time to try his guess. He'd been putting it off, in case it didn't work really. He got up.

Milo had begun to snooze on a seat by the door and the sudden movement startled him.

'Sir?'

Gaunt was on his feet, carelessly pulling his kitbag and luggage trunks from the wall locker.

'Let's hope the old man wasn't lying!' was all Gaunt said.

Which old man, Milo had no idea.

Gaunt rifled through his baggage. A silk-swathed dress uniform ended up on the floor. Books and data-slates spewed from pulled-open pouches.

Milo was fascinated for a moment. The commissar always packed his own effects, and Milo had never seen the few possessions Gaunt valued enough to carry with him. The boy glimpsed a bar of medals wound in tunic doth; a larger, grand silver starburst rosette that fell from its velvet lined case; a faded forage cap with Hyrkan insignia; a glass box of painkiller tablets; a dozen large, yellow slab-like teeth – ork teeth – drilled and threaded onto a cord; an antique scope in a wooden case; a worn buckle brush and a tin of silver polish; a tarot gaming deck which spilled out of its ivory box. The cards were stiff pasteboard, decorated with commemorative images of a liberation festival on somewhere called Gylatus Decimus. Milo bent to collect them up before Gaunt trampled them. They were clean and new, never used; the lid of the box was inscribed with the letters D. O.

Unheeding, Gaunt pulled handfuls of clothes out of his kit-bag and flung them aside. Milo grinned. He felt somehow privileged to see this stuff, as if the commissar had let him into his mind for a while.

Then something else bounced off the accumulating clutter on the deck and Milo paused. It was a toy battleship, rudely carved from a hunk of plastene. Enamel paint was flaking away, and some of the towers and gun turrets had broken off. Milo turned away. There was something painful about the toy, something that let him glimpse further into Ibram Gaunt's private realm of loss than he wanted to go.

The feeling surprised him. He retreated a little, dropping some of the cards he had been shuffling back into their ivory box, and was glad of the excuse to busy himself picking them up.

Gaunt suddenly turned from the mess, a look of triumph in his eyes. He held up a tarnished, old signet ring between his fingers.

'What you were looking for, commissar?' Milo asked brightly, feeling a comment was expected.

'Oh yes. Dear old Uncle Dercius, that bastard. Gave it me as a distraction that night—' Gaunt stopped suddenly, thoughts clouding his face.

He sat down on the bunk next to Milo, glancing over and chuckling sadly as he saw the deck the boy was sorting. 'Souvenirs. Hnh. Emperor knows why I keep them. Never glance at them for years and then they only dredge up black memories.'

He took the cards and rifled through them, holding up some to show Milo, laughing sourly as he did so, as if the Tanith youth could understand the reason for humour. One card showed a Hyrkan flag flying from some tower or other, another showed a heraldic design with an ork's skull, another a moon struck by lightning from the beak of an Imperial eagle.

'Seventy-two reasons to forget our noble victory in the Gylatus World Flock,' he said mockingly.

'And the ring?' Milo asked.

Gaunt put the cards aside. He turned the milling on the signet mount and a short beam of light stabbed out of the ring. 'Feth! Still power in the cell, after all this time!'

Milo smiled, uncertain.

usa decryption ring. Officer level. A key to let senior staff access private or veiled data. A general's plaything. They used to be quite popular. This was issued to the commander-in-chief of the noble Jantine regiments, a lord of the very highest standing. And that old bastard gave it to a little boy on Manzipor.'

Gaunt dug the crystal out of his tunic pocket and held it over the ring's beam. He glanced at Milo for a second. There was a surprisingly impish, youthful glee in Gaunt's eyes that made Milo snort with laughter.

'Here goes,' Gaunt said. He slipped the base of the crystal onto the ring mount. It fitted perfectly and engaged with a tiny whirr. Locked in place, as if the stone was now set on the ring band like an outrageously showy gem, it was illuminated by the beam of light. The crystal glowed.

'Come on, come on…' Gaunt said.

Something started to form in the air a few centimetres above the ring, a pict-form, neon bright and lambent in the dimness of the cabin.

The tight, small holographic runes hanging in the air read: 'Authority denied. This document may only be opened by Vermilion level decryption as set by order of Senthis, Administratum Elector, Pacificus calendar 403457.M41. Any attempts to tamper with this data-receptade will result in memory wipe.'

Gaunt cursed and slipped the crystal off the mount, cancelling the ring's beam. Too old, too damn old! Feth, I thought I had it!'

'I don't understand, sir.'

The clearance levels remain the same, but they revise the codes required to read them at regular intervals. Dercius's ring would certainly have opened a Vermilion text thirty years ago, but the sequences have been overwritten since then. I should have expected Dravere to have set his own confidence codes. Damn!'

Gaunt looked like he was going to continue cursing, but there was a sharp knock at the door of his quarters. Gaunt pocketed the crystal smartly and opened the door. Trooper Uan, one of the corridor sentries, looked in at him.

'Sergeant Blane has brought visitors to you, sir. We've checked them for weapons, and they're clean. Will you see them?'

Gaunt nodded, pulling on his cap and longcoat. He stepped out into the corridor. When he saw the identity of the visitors, Gaunt waved his men back and walked down to greet them.

It was Colonel Zoren, the Vitrian commander, and three of his officers.

'Well met, commissar,' Zoren said curtly. He and his men were dressed in ochre fatigues and soft caps.

'I didn't realise you Vitrians were aboard,' Gaunt said.

'Last minute change. We were bound for the Japhet but there was a problem with the boarding tubes. They re-routed us here. The regiments scheduled for the Absalom took our places on the Japhet once the technical problems were solved. My platoons have been given the barrack decks aft of here.'

'It's good to see you, colonel.'

Zoren nodded, but there was something he was holding back, Gaunt sensed. 'When I

learned we were sharing the same transport as the Tanith, I thought perhaps an interaction would be appropriate. We have a mutual victory to celebrate. But—'

'But?'

Zoren dropped his voice. 'I was attacked in my quarters this morning. A man dressed in unmarked navy overalls was searching my belongings. He rounded on me when I came in. There was a struggle. He escaped.'

Gaunt felt his anger return. 'Go on.'

'He was looking for something. Something he thought I might have, something he had failed to find elsewhere. I thought I should tell you directly.'

Milo, Uan and everyone in the corridor, including Zoren himself, was surprised when Gaunt grabbed the Vitrian colonel by the front of his tunic and dragged him into his quarters. Gaunt slammed the door shut after them.

Alone in the room, Gaunt turned on Zoren, who looked hurt but somehow not surprised.

That was a terribly well-informed statement, colonel.'

'Naturally.'

'Start making sense, Zoren, or I'll forget our friendship.'

'No need for unpleasantness, Gaunt. I know more than you imagine and, I assure you, I am a friend.'

'Of whom?'

'Of you, of the Throne of Terra, and of a mutual acquaintance I know him as Bel Torthute. You know him as Fereyd.'

EIGHT

'It's…' Colonel Draker Flense began. 'It's a lot to think about.'

He was answered by a snigger that did nothing to calm his nerves. The snigger came from a tall, hooded shape at the rear of the room, a figure silhouetted against a window of stained glass imagery which was lit by the flashes and glints of the irnmaterium.

You're a soldier, Flense. I don't believe thinking is part of the tob description.'

Flense bit back on a sharp answer. He was afraid, terribly afraid of the man in the multi-coloured shadows of the window. He shifted uneasily, dying for a breathe of fresh air, his throat parched. The chamber was thick with the smoke from the obscura water-pipe on its slate plinth by the steps to the window. The nectar-sweet opiate smoke swirled around him and stole all humidity from the air. His mind was slack and torpid from breathing it in.

Warrant Officer Lekulanzi, stood by the door and the three shrouded astropaths grouped in a huddle in the shadows to his left didn't seem to mind. The astropaths were a law unto themselves, and Flense had recognised the pallor of an obscura addict in Lekulanzi's face the moment the warrant officer had arrived at his quarters to summon him. Flense had lead an assault into an addict-hive on Poscol years before. He had never forgotten the sweet stench, nor the pallor of the halfhearted resistance.

The figure at the windows stepped slowly down to face him. Flense, two metres tall without his jackboots, found himself looking up into the darkness of the cowl.

'Well, colonel?' whispered the voice inside the hood.

'I— I don't really understand what is expected of me, my lord.'

Inquisitor Golesh Constantine Pheppos Heldane sniggered again. He reached up with his ring-heavy fingers and turned back his cowl. Flense blinked. Heldane's face was high and long, like some equine beast. His wet, sneering mouth was full of blunt teeth and his eyes were round and dark. Fluid tubes and fibre-wires laced his long, sloped skull like hair braids. His huge skull was hairless, but Flense could see the matted fur that coated his neck and throat. He was human, but his features had been surgically altered to inspire terror and obedience in those he… studied. At least, Flense hoped it was a surgical alteration.

You seem uneasy, colonel. Is it the circumstance, or my words?'

Flense found himself floundering for speech again. 'I've never been admitted to a sacrosanctorium before, lord,' he began.

Heldane extended his arms wide – too wide for anything but a skeletal giant like Heldane, Flense shuddered – to encompass the chamber. Those present were standing in one of the Absalom's astropath sanctums, a chamber screened from all intrusion. The walls were null-field dead spaces designed to shut out both the material world and the screaming void of the Immaterium. Sound-proofed, psyker-proofed, wire-proofed, these inviolable cocoons were dedicated and reserved for the astropathic retinue alone. They were prohibited by Imperial law. Only a direct invitation could admit a blunt human such as Flense.

Blunt. Flense didn't like the word, and hadn't been aware of it until Lekulanzi had used it. Blunt. A psyker's word for the non-psychic. Blunt. Flense wished by the Ray of Hope he could be elsewhere. Any elsewhere.

'You are discomforting my cousins,' Heldane said to Flense, indicating the three astropaths, who were fidgeting and murmuring. 'They sense your reluctance to be here. They sense their stigma.'

'I have no prejudices, inquisitor.'

Yes, you have. I can taste them. You detest mind-seers. You despise the gift of the astropath. You are a blunt, Flense. A ^ense-dead moron. Shall I show you what you are missing?'

Flense shook. 'No need, inquisitor!'

'Just a touch? Be a sport.' Heldane sniggered, droplets of spittle flecking off his thick teeth.

Flense shuddered. Heldane turned his gaze away slowly and then snapped back suddenly. Impossible light flooded into Flense's skull. For one second, he saw eternity. He saw the angles of space, the way they intersected with time. He saw the tides of the Empyrean, and the wasted fringes of the Immaterium, the fluid spasms of the Warp. He saw his mother, his sister, both long dead. He saw light and darkness and nothingness. He saw colours without name. He saw the birth torments of the genestealer whose blood would scar his face. He saw himself on the drill-field of the Schola on Primagenitor. He saw an explosion of blood. Familiar blood. He started to ay. He saw bones buried in rich, black mud. He realised they, too, were his own. He looked into the sockets. He saw maggots. He screamed. He vomited. He saw a red-dark sky and an impossible number of suns. He saw a star overload and collapse. He saw-Too much.

Draker Flense fell to the floor of the sacrosanctorium, soiled himself and started to whimper.

'I'm glad we've got that straight,' Inquisitor Heldane said. He raised his cowl again. 'Let me start over. I serve Dravere, as you do. For him, I will bend the stars. For him, I will torch planets. For him, I will master the unmasterable.'

Flense moaned.

'Get up. And listen to me. The most priceless artefact in space awaits our lord in the Menazoid Clasp. Its description and circumstance lies with the Commissar Gaunt. We will obtain that secret. I have already expended precious energies trying to reach it. This Gaunt is… resourceful. You will allow yourself to be used in this matter. You and the Patricians. You already have a feud with them.'

'Not this… not this…' Flense rasped from the floor.

'Dravere spoke highly of you. Do you remember what he said?'

'N-no…'

Heldane's voice changed and became a perfect copy of Dravere's. 'If you win this for me, Flense, I'll not forget it. There are great possibilities in my future, if I am not tied here. I would share them with you.'

'Now is the time, Flense,' Heldane said in his own voice once more. 'Share in the possibilities. Help me to acquire what my Lord Dravere demands. There will be a place for you, a place in glory. A place at the side of the new warmaster.'

'Please!' Flense cried. He could hear the astropaths laughing at him.

'Are you still undecided?' Heldane asked. He stepped towards the curled, foetal Colonel. 'Another look?' he suggested.

Flense began to shriek.

NINE

'They're excluding us,' Feygor said out of the silence.

Rawne snapped an angry glance round at his adjutant, but he knew what the lean man meant. It had been four hours since the rest of the officers had been called into their meeting with Gaunt. How convenient that he and his platoon had been excluded. Of course, if what Corbec said was true and there was trouble aboard, a good picket was essential. But in the natural order of things, it should have been Folore's platoon, the sixteenth, who took first shift.

Rawne grunted a response an

d led his team of five men down to the junction with the next corridor. They'd swept this area six times since they had begun. Just draughty hull-spaces, dark corners, empty stores, dusty floors and locked hatches. He checked the time. A radio message from Lerod twenty minutes earlier had informed him that the shift change would take place on the next hour. He ached. He knew the men with him were tired and cold and in need of stove-warmth, caffeine, relaxation. By extension, all of his platoon, all fifty of them spread out patrolling the perimeter of the Ghosts' barrack deck in squads of five, would be demoralised and hungry too.

Rawne thought, as he often did, of Gaunt. Of Gaunt's motives. From the start, back at the bloody hour of the Founding itself, he had shown no loyalty to the commissar. It had astonished him when Gaunt had raised him to major and given him the tertiary command of the regiment. He'd laughed at it at first, then qualified that laughter by imagining Gaunt had recognised his leadership qualities. Sometime later, Feygor, the only man in the regiment he thought of as a friend, and then only barely, had reminded him of the old saying: 'Keep your friends close and your enemies closer.'

There was no escape from the Guard, so Rawne had got on with making the best of his job. But he always wondered at Gaunt. If he'd been the colonel-commissar, with a danger like himself at his heels, he'd have called up a firing squad long since.

Ahead, Trooper Lonegin was checking the locks on a storage bin. Rawne scanned the length of the corridor they had just advanced through.

Feygor watched his commander slyly. Rawne had been good to him – and they had worked together in the militia of Tanith Attica before the Founding. Quite a tasty racket they had running there until the fething Imperium rolled up and ruined it. Feygor was the bastard son of a black marketeer, and only his sharp mind and formidable physical ability had got him a place in the militia, and then the Imperial Guard. Rawne's background had been select. He didn't talk about it much, but Feygor knew enough to know that that Rawne's family had been rich, merchants, local politicians, local lords. Rawne had always had money, stipends from his father's empire of timber mills. But as the third son, he was never going to be the one to inherit the fortune. The militia service – and the opportunities for self advancement – had been the best option.

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

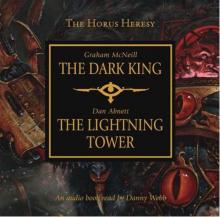

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower