- Home

- Dan Abnett

First and Only Page 15

First and Only Read online

Page 15

Gaunt raised an eyebrow. 'How so?'

'I understood assassins liked to toxify their blades as insurance.' Dorden said simply.

'I never said it was an assassin.'

You didn't have to. I may be a non-combatant. Feth, I may be an old fool, but I didn't come down in the last barrage.'

'Don't trouble yourself with it, Dorden,' Gaunt said, flexing his arm again against the medic's advice. It stung, ached, throbbed. 'You've worked your usual magic. Stay impartial. Don't get drawn in.'

Dorden was scrubbing his suture clamp and wound probes in a bowl of filmy antiseptic oil. 'Impartial? Do you know something, Ibram Gaunt?'

Gaunt blinked as if slapped. No one had spoken to him with such paternal authority since the last time he had been in the company of his Uncle Dercius. No… not the last time…

Dorden turned back, wiping the tools on sheets of white lint.

'Forgive me, commissar. I— I'm speaking out of turn.'

'Speak anyway, friend.'

Dorden jerked a lean thumb to indicate out beyond the archway into the barrack deck. These are all I've got. The last pitiful scraps of Tanith genestock, my only link to the past and to the green, green world I loved. I'll keep patching and mending and binding and sewing them back together until they're all gone, or I'm gone, or the horizons of all known space have withered and died. And while you may not be Tanith, I know many of the men now treat you as such. Me, I'm not sure. Too much of the chulan about you, I'd say.'

'Koolun?'

'Chulan. Forgive me, slipping in to the old tongue. Outsider. Unknown. It doesn't translate directly.'

'I'm sure it doesn't.'

'It wasn't an insult. You may not be Tanith-breed, but you're for us every way. I think you care, Gaunt. Care about your Ghosts. I think you'll do all in your power to see us right, to take us to glory, to take us to peace. That's what I believe, every night when I lay down to rest, and every time a bombardment starts, or the drop-ships fall, or the boys go over the wire. That matters.'

Gaunt shrugged – and wished he hadn't. 'Does it?'

'I've spoken to medics with other regiments. At the field hospital on Fortis, for instance. So many of them say their commissars don't care a jot about their men. They see them as fodder for the guns. Is that how you see us?'

'No.'

'No, I thought not. So, that makes you rare indeed. Something worth hanging on to, for the good of these poor Ghosts. Feth, you may not be Tanith, but if assassins are starting to hunger for your blood, I start to care. For the Ghosts, I care.'

He fell silent.

'Then I'll remember not to leave you uninformed,' Gaunt said, reaching for his undershirt.

'I thank you for that. For a chulan, you're a good man, Ibram Gaunt. Like the anroth back home.'

Gaunt froze. 'What did you say?'

Dorden looked round at him sharply. 'Anroth. I said anroth. It wasn't an insult either.'

'What does it mean?'

Dorden hesitated uneasily, unsettled by Gaunt's hard gaze. The anroth… well, household spirits. It's a cradle-tale from Tanith. They used to say that the anroth were spirits from other worlds, beautiful worlds of order, who came to Tanith to watch over our families. It's nothing. Just an old memory. A forest saying.'

'Why does it matter, commissar?' said a new voice.

Gaunt and Dorden looked around to see Milo sat on a bench seat near the door, watching them intently.

'How long have you been there?' Gaunt asked sharply, surprising himself with his anger.

'A few minutes only. The anroth are part of Tanith lore. Like the drudfellad who ward the trees, and the nyrsis who watch over the streams and waters. Why would it alarm you so?'

'I've heard the word before. Somewhere,' Gaunt said, getting to his feet. 'Who knows, a word like it? It doesn't matter.' He went to pull on his undershirt but realised it was ripped and bloody, and cast it aside. 'Milo. Get me another from my quarters,' he snapped.

Milo rose and handed Gaunt a fresh undershirt from his canvas pack. Dorden covered a grin. Gaunt faltered, nodded his thanks, and took the shirt.

Both Milo and the medical officer had noticed the multitude of scars which laced Gaunt's broad, muscled torso, and had made no comment. How many theatres, how many fronts, how many life-or-death combats had it taken to accumulate so many marks of pain?

But as Gaunt stood, Dorden noticed the scar across Gaunt's belly for the first time and gasped. The wound line was long and ancient, a grotesque braid of buckled scar-tissue.

'Sacred Feth!' Dorden said too loudly. 'Where—'

Gaunt shook him off. 'It's old. Very old.'

Gaunt slipped on his undershirt and the wound was hidden. He pulled up his braces and reached for his tunic.

'But how did you get such a—'

Gaunt looked at him sharply. 'Enough.'

Gaunt buttoned his tunic and then put on the long leather coat which Milo was already holding for him. He set his cap on his head.

'Are the officers ready?' he asked.

Milo nodded. 'As you ordered.'

With a nod to Dorden, Gaunt marched out of the infirmary.

FIVE

It had crossed his mind to wonder who to trust. A few minutes' thought had brought him to the realisation that he could trust them all, every one of the Ghosts from Colonel Corbec down to the lowliest of the troopers. His only qualm lay with the malcontent Rawne and his immediate group of cronies in the third platoon, men like Feygor.

Gaunt left the infirmary and walked down the short com-panionway into the barrack deck proper. Corbec was waiting.

Colm Corbec had been waiting for almost an hour. Alone in the antechamber of the infirmary, he had enjoyed plenty of time to fret about the things he hated most in the universe. First and last of them was space travel.

Corbec was the son of a machinesmith who had worked his living at a forge beneath a gable-barn on the first wide bend of the River Pryze. Most of his father's work had come from log-handling machines; rasp-saws, timber-derricks, trak-sleds. Many times, as a boy, he'd shimmied down into the oily service trenches to hold the inspection lamp so his father could examine the knotted, dripping axles and stricken synchromesh of a twenty-wheeled flatbed, ailing under its cargo of young, wet wood from the mills up at Beldane or Sottress.

Growing up, he'd worked the reaper mills in Sottress and seen men lose fingers, hands and knees to the screaming band saws and circular razors. His lungs had dogged with saw mist and he had developed a hacking cough that lingered even now. Then he'd joined the militia of Tanith Magna on a dare and on top of a broken heart, and patrolled the sacred stretches of the Pryze County nalwood groves for poachers and smugglers.

It had been a right enough life. The loamy earth below, the trees above and the far starlight beyond the leaves. He'd come to understand the ways of the twisting forests, and the shifting nal-groves and clearings. He'd learned the knife, the stealth patterns and the joy of the hunt. He'd been happy. So long as the stars had been up there and the ground underfoot.

Now the ground was gone. Gone forever. The damp, piney scents of the forest soil, the rich sweetness of the leaf-mould, the soft depth of the nalspores as they drifted and accumulated. He'd sung songs up to the stars, taken their silent blessing, even cursed them. All so long as they were far away. He never thought he would travel in their midst.

Corbec was afraid of the crossings, as he knew many of his company were afraid, even now after so many of them. To leave soil, to leave land and sea and sky behind, to part the stars and crusade through the Immaterium. That was truly terrifying.

He knew the Absalom was a sturdy ship. He'd seen its vast bulk from the viewspaces of the dock-ship that had brought him aboard. But he had also seen the great timber barges of the mills founder, shudder and splinter in the hard water courses of the Beldane rapids. Ships sailed their ways, he knew, until the ways got too strong for them and gave them up.

He hated it all.

The smell of the air, the coldness of the walls, the inconstancy of the artificial gravity, the perpetual constancy of the vibrating Empyrean drives. All of it. Only his concern for the commissar's welfare had got him past his phobias onto the nightmare of the Glass Bay Observatory. Even then, he'd focussed his attention on Gaunt, the troopers, that idiot warrant officer – anything at all but the cavorting insanity beyond the glass.

He longed for soil under foot. For real air. For breeze and rain and the hush of nodding branches.

'Corbec?'

He snapped to attention as Gaunt approached. Milo was a little way behind the commissar.

'Sir?'

'Remember what I was telling you in the bar on Pyrites?'

'Not precisely, sir… I… I was pretty far gone.'

Gaunt grinned. 'Good. Then it will all come as a surprise to you too. Are the officers ready?'

Corbec nodded perfunctorily. 'Except Major Rawne, as you ordered.'

Gaunt lifted his cap, smoothed his cropped hair back with his hands and replaced it squarely again.

'A moment, and I'll join you in the staff room.'

Gaunt marched away down the deck and entered the main billet of the barracks.

The Ghosts had been given barrack deck three, a vast honeycomb of long, dark vaults in which bunks were strung from chains in a herringbone pattern. Adjoining these sleeping vaults was a desolate recreation hall and a trio of padded exercise chambers. All forty surviving platoons, a little over two thousand Ghosts, were billeted here.

The smell of sweat, smoke and body heat rose from the bunk vaults. Rawne, Feygor and the rest of the third platoon were waiting for him on the slip-ramp. They had been training in the exercise chambers, and each one carried one of the shock-poles provided for combat practise. These neural stunners were the only weapons allowed to them during a crossing. They could fence with them, spar with them and even set them to long range discharge and target-shoot against the squeaking moving metal decoys in the badly-oiled automatic range.

Gaunt saluted Rawne. The men snapped to attention.

'How do you read the barrack deck, major?'

Rawne faltered. 'Commissar?'

'Is it secure?'

There are eight deployment shafts and two to the drop-ship hanger, plus a number of serviceways.'

Take your men, spread out and guard them all. No one must get in or out of this barrack deck without my knowledge.'

Rawne looked faintly perplexed. 'How do we hold any intruders off, commissar, given our lack of weapons?'

Gaunt took a shock-pole from Trooper Neff and then laid him out on the deck with a jolt to the belly.

'Use these,' Gaunt suggested. 'Report to me every half hour. Report to me directly with the names of anyone who attempts access.' Pausing for a moment to study Rawne's face and make sure his instructions were clearly understood. Gaunt turned and walked back up the ramp.

'What's he up to?' Feygor asked the major when Gaunt was out of earshot. Rawne shook his head. He would find out. Until he did, he had a sentry duty to organise.

SIX

The staff room was an old briefing theatre next to the infirmary annex. Steps led down into a circular room, with three tiers of varnished wooden seats around the circumference and a lacquered black console in the centre on a dais. The console, squat and rounded like a polished mushroom, was an old tactical display unit, with a mirrored screen in its top which had once broadcast luminous three-dimensional hololithic forms into the air above it during strategy counsels. But it was old and broken; Gaunt used it as a seat.

The officers filed in: Corbec, Dorden, and then the platoon leaders, Meryn, Mkoll, Curral, Lerod, Hasker, Blane, Folore… thirty nine men, all told. Last in was Varl, recently promoted. Milo closed the shutter hatch and perched at the back. The men sat in a semi-cirde, facing their commander.

'What's going on, sir?' Varl asked. Gaunt smiled slightly. As a newcomer to officer level briefings, Varl was eager and forthright, and oblivious to the usually reserved protocols of staff discussions. I should have promoted him earlier, Gaunt thought wryly.

This is totally unofficial. Ghost business, but unofficial. I want to advise you of a situation so that you can be aware of it and act accordingly if the need arises. But it does not go beyond this chamber. Tell your men as much as they need to know to facilitate matters, but spare them the details.'

He had their attention now.

'I won't dress this up. As far as I know – and believe me, that's no further than I could throw Bragg – there's a power struggle going on. One that threatens to tear this whole Crusade to tatters.

'You've all heard how much infighting went on after Warmaster Slaydo's death. How many of the Lord High Militant's wanted to take his place.'

'And that weasel Macaroth got it,' Corbec said with a rueful grin.

'That's Warmaster Weasel Macaroth, colonel,' Gaunt corrected. He let the men chuckle. Good humour would make this easier. 'Like him or not, he's in charge now. And that makes it simple for us. Like me, you are all loyal to the Emperor, and therefore to Warmaster Macaroth. Slaydo chose him to be successor. Macaroth's word is the word of the Golden Throne itself. He speaks with Imperium authority.'

Gaunt paused. The men watched him quizzically, as if they had missed the point of some joke.

'But someone's not happy about that, are they?' Milo said dourly, from the back. The officers snapped around to stare at him and then turned back equally sharply as they heard the commissar laugh.

'Indeed. There are probably many who resent his promotion over them. And one in particular we all know, if only by name. Lord Militant General Dravere. The very man who commands our section of the Crusade force.'

'What are you saying, sir?' Lerod asked with aghast disbelief. Lerod was a large, shaven-headed sergeant with an Imperial eagle tattoo on his temple. He had commanded the militia unit in Tanith Ultima, the Imperial shrine-city on the Ghost's lost homeworld, and as a result he, along with the other troopers from Ultima, were the most devoted and resolute Imperial servants in the Tanith First. Gaunt knew that Lerod would be perhaps the most difficult to convince. 'Are you suggesting that Lord General Dravere has renegade tendencies? That he is… disloyal? But he's your direct superior, sir!'

'Which is why this discussion is being held in private. If I'm right, who can we turn to?'

The men greeted this with uncomfortable silence.

Gaunt went on. 'Dravere has never hidden the fact that he felt Slaydo snubbed him by appointing the younger Macaroth. It must rankle deeply to serve under an upstart who has been promoted past you. I am pretty certain that Dravere plans to usurp the warmaster.'

'Let them fight for it!' Varl spat, and others concurred. 'What's another dead officer – begging your pardon, sir.'

Gaunt smiled. 'You echo my initial thoughts on the matter, sergeant. But think it through. If Dravere moves his own forces against Macaroth, it will weaken this entire endeavour. Weaken it at the very moment we should be consolidating for the push into new, more hostile territories. What good are we against the forces of the enemy if we're battling with ourselves? If it came to it, we'd be wide open, weak… and ripe for slaughter. Dravere's plans threaten the entire future of us all.'

Another heavy silence. Gaunt rubbed his lean chin. 'If Dravere goes through with this, we could throw everything away. Everything we've won in the Sabbat Worlds these last ten years.'

Gaunt leaned forward. There's more. If I was going to usurp the Warmaster, I'd want a whole lot more than a few loyal regiments with me. I'd want an edge.'

'Is that what this is about?' Lerod asked, now hanging on Gaunt's words.

'Of course it is. Dravere is after something. Something big. Something so big it will actually place him on an equal footing with the warmaster. Or even make him stronger. And that is where we pitiful few come into the picture.' He paused for a moment.

'When I was on Pyrites, I came into possession of this…'

/>

Gaunt held up the crystal.

The information encrypted onto this crystal holds the key to it all. Dravere's spy network was transmitting it back to him and it was intercepted.'

'By who?' Lerod asked.

'By Macaroth's loyal spy network, Imperial intelligence, working to undermine Dravere's conspiracy. They are covert, vulnerable, few, but they are the only things working against the mechanism of Dravere's ascendancy.'

'Why you?' Dorden asked quietly.

Gaunt paused. Even now, he could not tell them the real reason. That it was foretold. 'I was there, and I was trusted. I don't understand it all. An old friend of mine is part of the intelligence hub, and he contacted me to caretake this precious cargo. It seemed there was no one else on Pyrites close enough or trusted enough to do it.'

Varl shifted in his seat, scratching his shoulder implant. 'So? What's on it?'

'I have no idea,' Gaunt said. 'It's encoded.'

Lerod started to say something else, but Gaunt added, 'It's Vermilion level.'

There was a long pause, accompanied only by Blane's long, impressed whistle.

'Now do you see?' Gaunt asked.

'What do we do?' Varl said dully.

'We find out what's on it. Then we decide.'

'But how—' Meryn began, but Gaunt held up a calming hand.

That's my job, and I think I can do it. Easily, in fact. After that… well, that's why I wanted you all in on this. Already, Dravere's covert network has attempted to kill me and retrieve the crystal. Twice. Once on Pyrites and now here again on the ship. I need you with me, to guard this priceless thing, to keep the Lord Militant General's spies from it. To cover me until I can see the way clear to the action we should take.'

Silence reigned in the staff room.

'Are you with me?' Gaunt asked. The silence beat on, almost stifling. The officers exchanged furtive glances. In the end, it was Lerod who spoke for them. Gaunt was particularly glad it was Lerod.

'Do you have to ask, commissar?' he said simply.

Gaunt smiled his thanks. He got up from the display unit and stepped off the dais as the men rose. 'Let's get to it. Rawne's already setting patrols to keep this barrack deck secure. Support and bolster that effort. I want to feel confident that the area of this ship given over to us is safe ground. Keep intruders out, or escort them directly to me. If the men question the precautions, tell them we think that those damn Patricians might try something to ease their grudge against us. Terra knows, that's true enough, and there are over four times our number of Patricians aboard this vessel on the other barrack decks. And the Patricians are undoubtedly in Dravere's pocket.

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

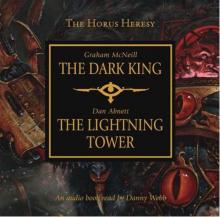

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower