- Home

- Dan Abnett

Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2 Read online

Border Princes

( Torchwood - 2 )

Dan Abnett

Dan Abnett. Border Princes

(Torchwood — 2)

For Gary Russell

ONE

The End of the World began on a Thursday night in October, just after eight in the evening.

It began with filthy, spitting rain creeping inland from the Bristol Channel, with a black SUV hammering east along the Penarth Road, with the bleep of a text message received.

‘Scale of one to ten?’ Owen asked. He was driving, peering out at traffic barely visible in the veil of rain.

‘One being slightly pressing and ten being insanely urgent?’ Jack wondered from the passenger seat.

‘Yeah.’

‘About twenty-six, twenty-seven,’ Jack replied mildly. He held up his mobile phone so that Owen could glance over and read the screen.

THE END OF THE WORLD.

‘Captain Analogy strikes again,’ said Owen.

‘There’s only room for one captain on this team,’ Jack replied, flipping the clam-shell mobile shut. ‘Uh, Owen…’ he added.

Looking at Jack’s mobile had taken Owen’s eyes away from the road long enough for tail lights to bloom bright like distress flares dead ahead. Owen stood on the brakes, rocking the SUV nose down, and downshifted to go around.

Headlights blinded them, oncoming and bright. A horn blared.

Owen made a tutting noise and hauled the SUV back into lane. Lurched hard in his inertia-reels by the drastic deceleration-acceleration-deceleration, Jack maintained a surprisingly beatific composure.

‘Sorry,’ said Owen, hands tight and white on the wheel. ‘Sorry about that.’

‘No problem.’

‘You seem remarkably relaxed.’

‘It’s the End of the World. A head-on prang on the Penarth Road seems somehow trivial by comparison.’

‘Ah,’ said Owen. The traffic ahead began to space out again.

‘Of course,’ said Jack, ‘he could be wrong.’

‘He’s usually right,’ Owen corrected. ‘Captain — sorry, Analogy Lad — has a nose for these things.’

The text bleep sounded again.

‘What’s he saying now?’ asked Owen.

‘Boiled egg,’ said Jack.

Owen floored the accelerator.

Boiled egg. ‘Four minutes or less.’

Gwen ran across the road in the sheeting rain towards the messy huddle of buildings cowering by the riverside. There were lights on in a nearby pub, a late shop, and a row of houses. The hiss of the rain was like persistent static.

The buildings directly ahead were derelict, and seemed to have been left in a state of schizophrenic disarray, undecided whether they wanted to grow up and be warehousing or a multi-storey car park. The pub’s neon window ads reflected in the long puddles on the road; pinks and reds and greens and Magners and Budweisers, stirred and puckered by the rain.

James was waiting under an arch of old, blackened brick. He started moving the moment she reached him.

‘Boiled egg?’ she asked, as she ran along beside him. ‘Really?’

‘Really.’

‘End of the World, or just the End of Cardiff?’

‘The latter is merely a sub-set of the former,’ he grinned. ‘Besides, I’m just relaying what Tosh told me.’

‘Where is she?’

‘Round the back.’

‘And what did she tell you?’

‘This is the blip she’s been seeing for a week, on and off. First real, solid fix.’

‘And it’s the End of the World why?’

‘Her systems crashed eighteen seconds after she painted it. I mean crash crashed. Forty-nine per cent of the Hub’s down. We left Ianto in tears.’

‘It’s aggressive, then?’

‘On a scale of one to ten?’ he asked.

‘Your scale or Jack’s?’

‘Mine.’

‘And?’

He shrugged, running up a short flight of rain-slick concrete steps. ‘Twenty-six, twenty-seven. It freaked the crap out of Tosh’s computers and they’re, you know, kind of the best us evolved apes have ever manufactured.’

They came out onto a vacant lot, tufted with virile weeds. The eastern end of the gravelly lot, marked by an ailing chain-link fence, was flooded with standing water six inches deep. Gwen could smell the river. The wind was cold, and held the particular tang of Autumn fighting a losing battle with Winter’s point men.

‘Oh!’ she said, suddenly unsteady. ‘Christ on a moped, did you feel that?’

He nodded. Nausea: a wallowing unease that reminded her of the car sickness she’d suffered as a child on family day-trips, the big back seat of the old Vauxhall Royale, stopping and starting in the tourist traffic all the way to Carmarthen.

‘I’ve got a headache,’ James said. ‘Have you got a headache?’

‘Yes,’ said Gwen, realising she absolutely had. ‘It came on suddenly.’

‘Like a switch?’

‘Like a switch, yeah. I can’t thick straight.’

‘Thick?’

‘What?’

‘You just said “thick”.’

‘I meant think.’

‘I know what you meant. I can’t thick straight either. I’m having real trouble focusing.’

‘You mean “trouble”,’ said Gwen, pinching the bridge of her nose.

‘What?’

‘You said “stubble”, but you mean “trouble”.’

‘I didn’t.’

Gwen looked at him. The cold rain spattered down on them. She was getting visual disturbance; squiggles of yellow light and peripheral flashes in the corners of her vision. She’d never suffered from migraines, but she’d read enough to know that this was what migraines were supposed to feel like.

‘What the bloody hell is this?’ she asked. She was slightly scared.

‘I don’t know,’ he said. He managed a grin and put on the beaky voice of his favourite cartoon character, ‘But I ain’t gonna get in no flap.’

That made her laugh. Jack was Torchwood’s rock and soul, but James was its heart. He could make her laugh in the face of the End of the World. Or Cardiff, whichever occurred first.

James turned away from her. ‘Game face,’ he said. ‘We’re on.’

Someone was running towards them, running right across the flooded part of the lot and kicking up froths of water like Gene Kelly in a happy-go-lucky mood.

Gwen thought it was Toshiko at first glance, but it wasn’t. It was a slim girl in boy-cut jeans and a skinny rib T-shirt that bore the slogan I’ve got tits, so I win.

She was running kind of funny, Gwen thought, spastic, her arms shaking. Her thin, pram face was twitching and blinking.

‘Hello?’ James called out.

The girl stumbled to a halt and wavered in front of them, blinking at James, then at Gwen, and then at James again. Each swing of her head was abrupt and made her sway. Her fingers, dripping with rain, pinched and snapped like someone telling the old ‘he’s been giving it that all night’ lobster joke.

‘Big big big,’ she told them, slurring and emphasising the middle ‘big’. ‘Sham. Sixty Nine per cent. Of cat owners. Anthropomorphise. Gibbons. Big gibbons. Big Gibbon’s Decline and Fall,’ she added.

Then she dropped to her knees with such a hard, bony crunch, Gwen winced. Kneeling, the girl threw up on the gravel.

Gwen went to her quickly, trying to help her. The girl said something, and pushed Gwen away. Then she hurled again.

Even diluted by the wind and rain, her sick smelled wrong. There was a strong ketone stink. Behind that, half-masked, plastics and burned sugar.

‘It’s all right,’ said Gwen.

‘Big bi

g big,’ the girl slurred, and dry heaved like she was trying to exhale her liver.

Gwen looked up at James.

‘What the hell’s wrong with her?’ she asked. ‘And, also, ow! My headache’s getting worse.’

‘Mine too,’ he agreed. He was trying to be upbeat, but she could hear the tone. The pain. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘unless quiz night at the local pub has gone horribly wrong-’

The girl got up, shoving them aside. She fell down again, picked herself up once more and said, ‘Glory. Glory glory glory. Cantankerous. Is a good word.’

She swayed and looked at James. ‘Isn’t it?’

‘It is,’ he replied, reaching out his hand.

The girl laughed, and bubbles of snot came out of her nose. The heaves squeezed her again, and she convulsed, elbows digging into her sides, but nothing more came up.

‘Varnish,’ she said, gurgling, and ran away.

‘Don’t let her-’ Gwen began.

The girl didn’t get far. She ran blindly into a mouldering brick wall, bounced off it with an ugly smack, and fell flat on her back.

They ran to her. Her face and arms were grazed and bleeding. Her nose was broken. Blood ran out of it, turning pink in the steady downpour.

‘It’s all right, it’s all right,’ Gwen hushed. ‘What’s your name? Can you tell me your name?’

‘Huw,’ the girl mumbled.

‘Well, there’s a switch,’ said James.

Gwen looked up at him. ‘She’s not Huw, you prat. Huw’s someone else.’

Huw ran down the riverside path, behind the glittering raindrop wall of the chain link. He thought he was running well, really sprinting, but to an observer, he would have looked like someone doing a sensationally bad Planet of the Apes impression.

He stumbled and slapped into the fence, making it trampoline and jingle. Collected rainwater shivered off the diamond links.

He sagged.

‘Let me help you,’ said the woman materialising out of the rain behind him. She was beautiful, Huw thought, blinking at her. She was slender and very cool beans in her black leather coat.

‘My name is Toshiko,’ the woman told him. ‘Let me help you. Tell me your name. Tell me what happened.’

Huw flopped back onto the grass and broken asphalt, one hand still clinging to the quivering fence.

‘There are,’ he began, but stopped. His voice sounded funny, as if his ears were stuffed full of cotton wool. Maybe they were. Had he done that? Perhaps he had. Earlier on, in the bathroom, swallowing the last of the aspirin. There had been a baggie of cotton wool balls by the sink. Laney’s, for make-up. Had he… had he?

It was so hard to think. To remember. His own name. Laney’s name. No, Laney’s name was Laney. Laney, where are you?

‘Talk to me,’ said the woman called Toshiko. ‘What were you trying to tell me?’

‘There are,’ Huw began again, ignoring the woolly sound of his voice, ‘there are numbers, and there are two blue lights and they move, and they move about, like this.’

He pulled his hand free of the dripping chain link and moved it around his other hand, describing curious, geometric patterns in the air.

‘They move. They move. They move about. They’re big lights. Big big big.’

His thready voice emphasised the middle of the three ‘bigs’.

Toshiko crouched beside him. ‘Lights? And numbers?’

Huw nodded. ‘Big big big. Flashing and moving. Blue. Oh, sometimes red. Red is dead. Blue is true. Big big big.’

‘What are the numbers?’ Toshiko asked him.

‘My name is Huw!’ he blurted, as if he’d just that minute remembered.

‘Oh, well, hello Huw. Tell me about the numbers and the lights.’

Huw’s head rolled drunkenly. He was blinking very fast, and the muscles in his face were ticking. ‘Huw is blue. Huw is true. Big big big.’

‘The numbers, Huw-’

‘Abstract numbers,’ he said, very clearly and suddenly, fixing her with a stare.

Toshiko looked back at him. Jeans, a vest top, a ratty Hoxton fin ruined by the rain. No way this ‘Huw’ knew about abstract numbers.

‘Huw, tell me about the abstract numbers.’

Huw was fiddling with his left ear. He pulled out a clump of cotton wool. It was soaked in blood.

‘Shit,’ he muttered. ‘I think my brain’s burst.’

‘Huw,’ Toshiko soothed.

‘Oh no!’ he wailed suddenly, writhing.

‘Oh no! Go away! Don’t look at me! Leave me alone!’

Toshiko started back. She realised Huw had just wet himself. She could smell it. He was mortified by the indignity.

That suggested he wasn’t drunk.

‘Huw…’

‘My head does hurt,’ he moaned.

‘So does mine,’ she agreed. It really, really did. ‘Tell me more about the numbers and the lights. Where did they come from?’

Boiled egg. Boiled egg. She was acutely aware that they were running out of time. Completely out of time.

‘Big big big,’ Huw replied. ‘Stephi Graff. Giraffe. Ron Moody. Bastard. Twins. Illegitimate twins. On the cover of Hello! magazine. Do you know that magazine? Very much the model of a modern major overhaul.’

‘Huw? Come on! Huw?’

He smiled at her, blinking all the time.

Then he died.

His eyeballs went slack, and his head flopped back, and a puff of smoke trickled up out of his open mouth.

The smoke smelled of burned sugar, plastic and faeces.

Knifed by the same pain that had killed him, Toshiko fell to her knees, wincing.

‘He lost the Amok,’ a voice behind her said.

Toshiko looked around.

The tramp stood in the beating rain, watching her. He seemed huge, but that was because he was wearing too many old coats. His filthy beard was strung with rainwater droplets like a Christmas tree’s decorations. He reeked of mud and factory waste. His arms were weighed down by two heavy carrier bags. Sainsbury’s.

‘He lost the what?’ Toshiko asked, rising.

‘The Amok,’ the tramp replied. There was no way of telling how old he was. Thirty? Sixty? Life had run him down without stopping.

He set his bulging carrier bags down at his feet. ‘Huw had the Amok, but he lost. Donny had it before him, and he lost too. Before Donny, Terry. Before Terry, Malcolm. Before Malcolm, Bob. Before Bob, Ash’ahvath.’

‘Before Bob who?’

‘Ash’ahvath,’ the tramp said.

‘As in the Middlesex Ash’ahvath’s?’

The tramp sniggered and shook his head so hard raindrops flew out of his beard, like a dog shaking itself after bath-time. ‘You’re funny. I don’t know no Ash’ahvath. It was just the last name on the list.’

‘I see,’ said Toshiko, slowly rising to her feet. ‘Do you have the Amok now? What’s your name?’

‘John Norris,’ replied the tramp, crouching down to sort through his carrier bags. ‘John Norris. I was all right once, you know.’

‘You’re all right now, John,’ she said.

‘I’m not. I’m not. I had a good job. A company car. It was a Rover. GL. I had my own parking space. They called me Mr Norris.’

‘What happened?’

‘Workforce rationalisation. The wife moved to her sister’s place. I haven’t seen my boy in five years.’

The tramp began to weep.

‘Mr Norris, we can sort this all out,’ Toshiko said, stepping towards him. Her head was throbbing. ‘Please, do you have the Amok?’

He nodded, sniffling, and rifled around in one of his carrier bags.

‘It’s in here somewhere.’ He glanced up at her. ‘Big big big,’ he added. Emphasis on the middle ‘big’.

‘Just show it to me. The Amok.’

‘Oh, right, here it is,’ he said. He drew something out of the carrier bag. It was a ten-by-eight clip frame in which were pressed three photographs. A woman. A boy. A woman a

nd a boy.

‘Mr Norris, that’s not the Amok, is it?’ Toshiko said gently.

The tramp shuddered. He shook his head, shoulders hunched. ‘No,’ he whimpered. He struck the clip frame against the path and shattered it.

‘Mr Norris?’

When he turned to face her, he was holding a sliver of the clip frame glass in his hand. The broken edges were so sharp, and his grip on it so tight, blood dribbled out between his dirty fingers.

‘Oh shit,’ said Toshiko, backing away abruptly.

The tramp lunged.

TWO

Fat radials hissed as the SUV came to a halt. Jack and Owen got out into the rain. Jack tried his mobile.

‘No signal,’ he said to Owen.

Jack looked around. ‘Tosh? James?’ he yelled. There was no answer.

‘Let’s try in there,’ said Owen, making off towards the nearby pub. It looked bright and inviting, the frosted glass oblongs of its windows warmed from within by yellow light.

Jack followed him. Owen had gone a few steps when he paused and lowered his head.

‘What?’

‘Bastard of a headache I’ve got, all of a sudden,’ Owen groaned, his hand raised to his temple.

‘I thought you were going to have a quiet one last night,’ Jack said sourly, pushing past Owen towards the door of the public bar.

‘It’s not that kind of headache,’ Owen complained, his thin mouth more of a downward curve than usual. ‘Buggering Christ, can’t you feel that?’

‘Your headache?’ replied Jack. ‘Funnily enough, no.’ He hesitated. ‘But I know what you mean. I can feel something.’

He opened the pub door and went inside. Owen followed. It was as cheerfully grotty as any of Cardiff’s arse-end public houses, marinated in a smell of fags and malt. An aimless clatter-ping rang from the pinball machine and ‘If You Don’t Know Me By Now’ issued from the jukebox.

‘So where is everyone?’ Owen asked.

The public bar was empty. So was the saloon. Empty chairs loitered around Formica-topped tables on which a few half-empty glasses and the occasional open packet of nuts waited. There was no sign of disarray, and no sign of any bar staff. The drawer of the public bar’s cash register was open.

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

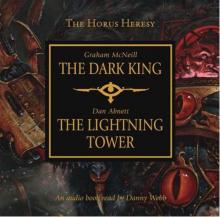

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower