- Home

- Dan Abnett

Penitent Page 9

Penitent Read online

Page 9

‘I like this better,’ Lightburn said.

‘Better than the arch?’

‘Infinitely,’ he replied. ‘That arch leads nowhere I want to go. I feels it in my bones.’

‘Agreed,’ I said, ‘and I cannot say for why. That vista, and the sound of the sea, it frightens me.’

‘Me too,’ he said. ‘But this… This way goes up.’

I smiled, and took his hand, so that we might ascend together, but the seabird cry came again, now very loud. We turned and saw, to our amazement, a great bird fly in through the towering arch, and come to rest upon the inscribed block. Its wings were mighty, silk-white, and fully five metres in span, furling as it perched to rest.

But it was no bird.

It was a winged man. No, a winged giant. No, an angel. My mind could not reason it. It was the living cousin of the dead thing I had seen.

Naked, he seemed a god. His corded physique was that of the legend-heroes whose statues supported the portico of the Prefect’s mansion. His skin was porcelain white, his hair long, black and bedraggled. He crouched upon the King Door block like a perfect messenger of the divine. He seemed almost twice the size of a mortal human.

Lightburn and I had both frozen on the bottom step, astounded by the vision, but my heart lifted. Here, here, here was the angel, the living angel, I had yearned to find. Here, I was sure, was truth and answers, the clear and golden light that would banish the daemon-darkness of my life.

The angel slowly turned its head to look at us. Its wild black mane hung down, almost across its eyes, framing its face. A beautiful face, quite the most beautiful I have ever seen: high cheekbones, a patrician’s nose, a wise and solemn mouth. I wondered what words it would speak to us.

The angel sniffed the air, its head bobbing like a falcon at hunt. Its eyes widened. They were entirely glossy and black within.

Its mouth opened. Its long fangs were like that of a wolf or carnodon. A drop of blood trickled from its lip down its alabaster chin.

With a cold howl of malice, it sprang, and flew at us.

CHAPTER 11

Of blood and fire

I know nothing. My life is built of contradictions. This I had suspected for a long while. On the decayed steps in the Below, it was confirmed, in a split second, with such a savage flourish as to seem almost spiteful.

Dark is light. Good is bad. I am and I am not. I walk with a man who seems loyal to the Throne and is yet branded a heretic. I shun another who I am told is my enemy, yet is also a stalwart servant of the highest powers. The Maze Undue was an Inquisitorial school, and yet it was the Cognitae, and yet the Cognitae and the Inquisition cannot easily be untied. Orphaeus was a lord hero, but yet the King in Yellow is dark menace. Queen Mab is a city, and yet it is also another, and neither are whole or together. I am hunted by many, yet I am a pariah. I have made a friend, or at least amiable company, of a daemon, and yet a bright angel seeks to rip out my throat.

All is deceit. Nothing wears a true face or uses a true name. Nothing is as it appears to be, as if the whole universe were busily playing out a function, ‘guised in cunning. The mad are sane, the blind can see, the sane are otherwise demented, good is evil, and up, for all I care, is down.

The angel, the beautiful angel, flew at me, screaming, fangs bared. It flew at me not just as a predator, not just as some instrument of murder, but as the brittle punchline of some elaborate joke. An angel of death. A lightness of dark. A beautiful horror.

Look upon me! it seemed to scream. Look upon me and see the utter folly of your mind! You longed for me, and searched for me, and here I am, nothing more than death!

Its speed was that of a whip’s crack, a winter owl stooping upon its hapless prey. Its power was ungodly. I knew I could neither move aside, nor fight it, even if there had been time or means to do either.

There was not. And I was frozen, besides, in abject terror.

It smashed poor Lightburn aside like a twig. I scarcely felt the impact of its strike. It bore me backwards, up the old, grand steps, clutched in its grip, its scream in my ears. I felt the stone density of it, the heat of its skin, the sting of its wet hair lashing my face. I smelled the scent of it, clean but sour, like a raptor, and the copper gust of its bloody breath.

It landed halfway up the flight, and cradled me in hands that could have enveloped my head. I heard the rippling crack of its wingbeat. It had my head in its long fingers, twisting it roughly as if to snap my neck. I felt it sniff the back of my skull.

It could smell the blood there. It had smelled it from across the chamber.

An animal growl rose in its throat, like fierce lava bubbling up a volcanic flue.

Blind, I snapped off my cuff.

The ravening angel shrieked and recoiled, dropping me like a white-hot ingot. I landed hard across the edges of the marble steps, bruising thigh and hip and ribs, and striking the back of my head. Sharp pain detonated like a grenade as the contusion hit against marble. I cried out, blinded by bright-coloured spots and sparks of light.

My senses swam. I sat up. The angel was falling backwards down the steps, bouncing and rolling, folded almost in a ball, and clawing at its own face.

It did not like my blankness at all.

As for Lightburn, he lay nearby, propped awkwardly on the steps where he had been knocked down, his back against the wall, gashes bleeding on his cheek and behind his ear. His glow-globe lay at his feet. He gazed in vacant dread at the killer angel now coiled in pain and mewling at the foot of the steps.

‘Renner–’

He did not reply.

‘Renner, get up! We have to go!’

He turned to the sound of my voice, and shuddered. The angel’s assault had shocked him deeply, and left him especially vulnerable to the effect of my blankness. My proximity was distressing him very much.

I could not turn the cuff back on, for I was sure my null was all that was driving the angel off, but I would not leave Lightburn. I clattered down several steps until I was below Lightburn on the staircase, and that was enough. The cold focus of my nullity was now between him and the angel of death. He sprang up, galvanised by repulsion, and began to half run, half stumble up the steps to get away from the emptiness that chilled his soul.

I grabbed the light, and ran after him. I was, I knew full well, driving him, herding him like a piece of frightened livestock. He would run all the while the deadness of me was at his back.

The staircase was immense. At the very top was a lofty portico and a pair of huge and ancient gilded doors that faced the head of the stairs. The doors were six metres high. They stood ajar, and light shafted through the narrow gap.

Lightburn, still gripped in panic, burst through them. He turned, and scrabbled to shut them in my face, to keep the atrocity of me at bay.

I turned on my cuff.

‘Renner, let me through!’

He backed off, and I slipped through. The doors were immensely heavy, but there were iron slide-bolts on the inside.

‘Help me!’ I yelled, trying to heave the doors shut.

He stared at me, uncertain, and then moved to my assistance. We closed the doors, pushed home the bolts, and then dropped into its brackets a hefty bar.

I turned to him. He was ashen.

‘I am a blank, Lightburn,’ I said directly. ‘I am a null, what is called an untouchable. It is my curse, and now you have tasted the miserable lack of my presence when it is not limited. I’m sorry.’

He opened his mouth, but found there was nothing he could say.

‘I’m sorry,’ I said again. ‘I would have told you of this, and perhaps warned you what it could be like, but there was no time. Thus, it was an ugly shock.’

‘Did I know this about you?’ he asked.

‘You did.’

‘Was I all right with it?’

‘It

was, I think, why you stood by me in the first place,’ I said. ‘I am an outcast of the world as much as any psyker.’

He swallowed hard.

‘All right,’ he said. He looked at the bolted doors.

‘And… that?’ he asked.

‘An angel,’ I replied.

‘I would say there ain’t no such thing,’ he murmured, ‘except for that I saw it and felt its rage…’

He paused and gingerly touched his wounds.

‘I think it was a Blood Angel,’ I said.

‘What?’

‘An Astartes warrior, of the Old Ninth Legion.’

‘Are Astartes real?’ he asked. Then he shook his head and laughed grimly. ‘Why ask? After today, anythin’ is possible. Are angels real? Are daemons–’

He stopped and looked at me sharply.

‘Are daemons real too?’ he asked.

I chose not to answer. He had been traumatised enough for one day.

‘We must go,’ I said. I turned and started to walk, and he followed. We were in a vast and ruined hall, perhaps the reception chamber of what once had been a stately residence. Stained glow-globes, still functioning on low power, hung from the arched ceiling on long chains.

‘Someone dwells here still,’ he said.

‘Or the power is maintained, perhaps on automatic,’ I replied. ‘Do you recognise the place?’

He shook his head.

‘I do not know if we’ve even reached street level yet.’

The walls were decorated with elaborate frescos that were too dimmed by grime to understand. I thought they were scenes of triumphs and Imperial glories, for I could just make out noble figures in gold and crimson, swords brandished aloft, and revelling putti cavorting in blue skies. I did not intend to stop and study it in more detail. We picked our way between ormolu furniture left to rot, and pieces of ceiling plasterwork that had fallen in disrepair and shattered across the polished ouslite floor.

‘Ninth Legion,’ Lightburn muttered. ‘They wore red, didn’t they?’

‘According to the stories.’

‘But they didn’t have no wings…’

‘This from a man who, until two minutes ago, swore they did not exist. Now you are an expert?’

‘What Astartes have wings?’ he replied.

‘Their sire did,’ I answered.

‘Their sire, yes…’ Lightburn shuddered. ‘Sanguinus.’

‘Sanguinius,’ I corrected.

‘But…’ he pressed, ‘acceptin’ that they are real, the Astartes were heroes of the Throne. The mightiest of all. They weren’t no… blood-thirsting beasts.’

‘They were not, so the myths report,’ I said, ‘but up is down.’

‘It’s what?’

I held up my hand sharply. We were not alone.

Their approach had been as silent as the darkness they dwelt in. They had been lying in wait, perhaps, or drawn by our voices. The anatomists edged out of the shadows, or emerged from behind decayed chairs and side tables. Some had slings ready, others clutched bone axes or stabbing spears. They snuffled and growled, perhaps forty in total, and we were pinned, for they were both ahead of us and behind.

We drew our guns and swung back to back.

‘I have six rounds,’ Lightburn said.

‘I have three loads of four,’ I replied, though I knew there would be no reloading in the chaos of a fray.

‘Make ’em count,’ he advised, ‘then take one of their weapons when you’re out.’

The anatomists surged. Lightburn’s pistol barked, putting two on the floor. I fired my quad, aiming for body mass, and firing only one shot at a touch. My first bullet exploded a chest in a gout of blood. The quad’s ammunition was built for stopping power.

I checked, and put a second shot through a belly. The bone-keeper was spun off his feet before he could loose his spear, his blood dappling the white-powdered skin of the men behind him. My third shot took down two: it eviscerated the first, and then slug fragments struck the anatomist to his left, and he fell too, bleeding from the calf and wrist.

Our shots were overlapping, one boom-and-flash across the next. I had lost count of Renner’s firing. I thought he was out, then heard another boom.

But it was not Lightburn’s gun discharging.

It was the double doors splintering open, bolts sheared, bar snapped.

The killer angel burst into the hall, snarling. Two racing strides, and it was airborne, swooping the length of the ancient hall with titanic wingbeats that stirred the air like the rushing of breaking waves. It uttered a strigine shriek.

It swept into the rear of the anatomist pack charging me, striking like a giant hawk. As it had been when it assaulted us, the angel’s speed was beyond measure, too quick for the eye. The anatomists had barely turned before it commenced their destruction. Its strength was beyond measure, too. With bare hands alone, it tore limbs clean off, dug fingers through meat to rip out spines, crushed skulls. In seconds, it was drenched in blood, clamping teeth into the throats of flailing wretches, tearing.

Drinking.

It was drinking their blood as it killed them, like a raging sot demolishing half-finished glasses at a bar, tossing them aside to reach the next. It was the most appalling slaughter I had ever witnessed. The most barbaric extermination, a blind rending of flesh and cracking of bone.

The anatomist throng facing Lightburn beheld this dread scene, and turned tail. Perhaps they had seen its predation before, or the predation of its angelic kind. Perhaps that was why they had nailed its brother angel to a cross. The bone-keepers must have discovered that one dead, or sick, for there was no way they could ever have overcome such a killer.

I grabbed Lightburn’s arm and dragged him to run after the fleeing anatomists. The angel was almost done with the rest of them. A lake of blood spread from the mangled bodies surrounding him as it gorged upon the last. Lightburn could barely look away. He gazed in horrid fascination at the angel’s massacre.

‘Run!’ I cried.

He began to, but I knew we would not get far.

‘Renner,’ I said. ‘Renner! Look at me!’

He tore his gaze away from the spectacle of murder, and found my eyes.

‘I’m going to turn off my cuff. My limiter cuff. It is our only hope, but you must brace yourself.’

He nodded.

I turned off the cuff. I felt him tremble at my side, and I heard him stifle a murmur of discomfort.

The angel stopped killing. It let go of the shredded corpse it was feeding on, and let it drop with a splash. The angel was washed in gore, its face, its chest, its hands. Blood spats flecked the white skin of its massive arms, and hung like rubies on the frosty fibres of its feathers. Blood drops swung like garnets from the strands of its lank black hair.

Hunched, it turned to look at me. It grunted and growled, short barks like yelps of pain that aspirated blood from its nostrils and lips.

‘Go back,’ I said.

I took a step towards it. The angel took a step back, splashing blood underfoot.

‘You must go back,’ I said.

It shook its head, sending blood drops flying.

‘You must.’

It spoke. Its voice was too quiet to hear, as if it had not been used in a very long time.

‘What did you say?’ I asked. I took another step.

The angel coughed, and spat out black clots.

‘You take it away,’ it said. Its tone was flat, no more than a whisper.

‘What do I take away?’

‘The Thirst. The Rage and the Thirst.’

‘Are you Astartes, a Blood Angel?’ I asked.

The angel hesitated, as though it didn’t know how to answer, or did not understand the words.

‘Comus,’ it said.

‘Comus?’

‘Comus Nocturnus. That is my name. Was my name.’

It… or I should say, he, regarded me again, and brushed the blood-soaked hair from his face. He straightened up from his hunch. He was demigod tall, and the tips of the folded wings at his back made him taller.

‘Are you a null?’ he asked.

I nodded. ‘You say that calms you?’

‘It is… uncomfortable,’ he replied. ‘But I crave it too. My mind has not felt such peace for…’ He shrugged, an oddly emphatic gesture when one is in possession of giant wings. ‘I know not how long. What year is it?’

Before I could answer, the angel frowned.

‘I tried to kill you,’ he said. ‘You and the man beside you.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘And I fear you will do so again if I unblank.’

‘No,’ he replied. ‘I have slaked my thirst. Years of craving. It will not return for a while.’

He looked down at the grisly mess around him in what seemed like utter disgust.

‘I want nothing except to see the light again. Liberty from the darkness that has bound me. Do you know the way out?’

‘I think I can find it,’ I said.

‘We can’t–’ I heard Lightburn hiss.

‘What?’ I said, aside.

‘We can’t let that thing into the city,’ he said between clenched teeth. He was plainly terrified of the monstrous angel, but could barely bring himself to look at me.

‘Renner, I don’t think we can prevent that thing from doing anything,’ I said.

I kept my cuff set off.

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

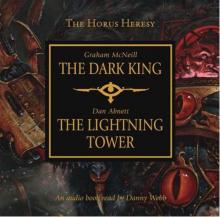

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower