- Home

- Dan Abnett

Eisenhorn Omnibus Page 61

Eisenhorn Omnibus Read online

Page 61

'It's beautiful/ I said, taking it from him. "What crystal did you use in the end?'

"What else?' he said. 'I carved that copy of your skull from the Lith itself

He came to see us off, to the docking barn where the gun-cutter had sat for so long. Nayl and Fischig were carrying the last things aboard. We had broken astropathic silence at last the night before, and informed Imperial Allied, Ortog Promethium, the Adeptus Mechanicus and the Imperial authorities of the fate that had befallen Cinchare minehead. We would be long gone before any of them arrived to begin recovery work.

Bure said farewell to Aemos, who shuffled away to the cutter.

'There's nothing adequate I can say/ I told the magos.

'Nor I to you, Eisenhorn. What of… the inmate?'

'I'd like you to do what I asked you. Give him mobility at least. But nothing more. He must remain a prisoner, now and always/

Very well. I expect to hear all about your victory, Eisenhorn. I will be waiting/

'May the Holy Machine God and the Emperor himself protect your systems, Geard/

'Thank you/ he said. Then he added something that quite took me aback, given his total belief and reliance on technology.

'Good luck/

I walked to the cutter. He watched me for a moment, then disappeared, closing the inner hatch after him.

That was the last time I ever saw him.

From Cinchare, the Essene ran back, fast and impatient, into the great territories of the Segmentum Obscurus, a three month voyage that we broke twice.

At Ymshalus, we stopped to transmit the prepared communiques, all twenty of them. Inshabel and Fischig left us too at that point; Inshabel to

secure passage to Elvara Cardinal to begin his work there, and Fischig for the long haul back to Cadia. It would be months, if not years, before we saw them again. That was a sorrowful farewell.

At Palobara, that crossroads on the border, busy with trading vessels and obscura caravans guarded by mercenary gunships, we stopped and transmitted the carta declaration. There was no going back now. Here, I parted company with Bequin, Nayl and Aemos, all of whom were heading back to the Helican sub-sector by a variety of means. Bequin's goal was Messina, and Aemos, with Nayl to watch over him, was bound for Gudrun. Another hard parting.

The Essene continued on for Orbul Infanta. This was now a lonely, waiting time. Each night, the remains of my company gathered in Maxilla's dining room and ate together: myself, Medea, Maxilla and Ungish. Ungish was no company, and even Medea and Maxilla had lost their sparkle. They missed the others, and I think they knew how dark and tough the time ahead would be.

I spent my days reading in the cabin library of the cutter, or playing regicide with Medea. I practised with Barbarisater in the hold spaces, slowly mastering the tricks of its weight and balance. I would never match a Carthae-born master, but I had always been good enough with a sword. Barbarisater was an extraordinary piece. I came to know it and it came to know me. Within a week, it was responding to my will, channelling it so hard that the rune marks glowed with manifesting psychic power. It had a will of its own, and once it was in my hands, ready, swinging, it was difficult to stop it pulling and slicing where it pleased. It hungered for blood… or if not blood, then at least the joy of battle. On two separate occasions, Medea came into the hold to see if I was bored enough for another round of regicide, and I had to restrain the steel from lunging at her.

Its sheer length was a problem: I had never used a blade so long. I worried that I would do my own extremities harm. But practice gave me the gift of it: long-armed, flowing moves, sweeping strokes, a tight field of severing. Within a fortnight, I had mastered the knack of spinning it over in my hand, my open palm and the pommel circling around each other like the discs of a gyroscope. I was proud of that move. I think Barbarisater taught it to me.

I worked with the rune staff too, to get used to its feel and balance. Though my aim was appalling, especially over distances further than three or four metres, I became able to channel my will, through my hands, into its haft and then project it from the crystal skull in the form of electrical bolts that dented deck plating.

There was, of course, no way I could test it for its primary use.

We reached the shrine world of Orbul Infanta at the end of the twelfth week. I had three tasks to perform here, and the first was the consecration of the sword and the staff.

With Ungish and Medea, I travelled down to the surface in one of the Essene's unremarkable little launches rather than the gun-cutter. We went to Ezropolis, one of Orbul Infanta's ten thousand shrine cities, in the baking heartland of the western continent.

Orbul Infanta is an Ecclesiarchy governed world, famously blessed with a myriad shrines, each one dedicated to a different Imperial saint, and each one the heart of a city state. The Ecclesiarch chose it as a shrine world because it lay on a direct line between Terra and Avignor. The most popular and thriving shrine cities lay on the coast of the eastern continent, and billions of the faithful flocked to them each year. Ezropolis was far away from such bustle.

Saint Ezra, who had been martyred in 670.M40, was the patron saint of undertaking and setting forth, which I took to be appropriate. His city was a shimmering growth of steel, glass and stone rising from the sun-cooked plains of the mid-west. According to the guide slates, all water was pumped in from the western coast along vast pipelines two thousand kilometres long.

We made planetfall at Ezra Plain, the principal landing facility, and joined the queues of pilgrims climbing the looping stairs into the citadel. Most were clad in yellow, the saint's colour, or had tags or swathes of yellow cloth adorning them. All carried lit candles or oil lamps, despite the unforgiving light. Ezra had promised to light a flame in the darkness to mark all those setting forth, and consequently his hagial colour was flame yellow.

We had done the necessary research. I wore a suit of black linen with a sash of yellow silk and carried a burning votive candle. Ungish was draped in a pale yellow robe the colour of the sun at dawn, and clutched a plaster figurine of the saint. Medea wore a dark red bodyglove under a tabard on which was sewn a yellow aquila symbol. She pushed the small grav-cart on which Barbarisater and the staff lay, wrapped in yellow velvet. It was common for pilgrims to cart their worldly goods to the shrine of Ezra, in order that they might be blessed before any kind of undertaking or setting forth could properly get underway. We blended easily with the teaming lines of sweating, anxious devotees.

At the top of the stairs, we entered the blessed cool of the streets, where the shadows of the buildings fell across us. It was nearly midday, and Ecclesiarchy choirs were singing from the platforms that topped the high, slender towers. Bells were chiming, and yellow sapfinches were being released by the thousand from basket cages in the three city squares. The thrumming ochre clouds of birds swirled up above us, around us, singing in bewilderment. They were brought in each day, a million at a time, from gene-farm aviaries on the coast, where they were bred in industrial quantities. They were not native to this part of Orbul Infanta, and would perish wifhin hours of release into the parched desert. It was reported that the plains around Ezropolis were ankle-deep with the residue of their white bones and bright feathers.

But still, they were the symbol of undertaking and setting forth, and so they were set loose by the million to certain death every midday. There is a terrible irony to this which I have often thought of bringing to the attention of the Ecclesiarchy.

We went to the Cathedral of Saint Ezra Outlooking, a significant temple on the western side of the city. On every eave and wall top we passed, sapfinches perched and twittered with what seemed to me to be indignation.

The cathedral itself was admittedly splendid, a Low Gothic minster raised in the last thirty years and paid for by subscriptions generated by the city fathers and priesthood. Every visitor who entered the city walls was obliged to deposit two high denomination coins into the take boxes at either side of the head of the approach s

tairs. A yellow robed adept of the priesthood was there to see it was done. The box on the left was the collection for the maintenance and construction of the city temples. The one on the right was the sapfinch fund.

We went inside Saint Ezra Outlooking, into the cool of the marble nave where the faithful were bent in prayer and the hard sunlight made coloured patterns on everything as it slanted through the huge, stained glass windows. The cool air was sweetened by the smoke of sweetwood burners, and livened by the jaunty singing from the cantoria.

I left Medea and Ungish in the arched doorway beside a tomb on which lay the graven image of a Space Marine of the Raven Guard Chapter, his hands arranged so as to indicate which holy crusade he had perished in.

I found the provost of the cathedral, and explained to him what I wanted. He looked at me blankly, fidgeting with his yellow robes, but I soon made him understand by depositing six large coins into his alms chest, and another two into his hand.

He ushered me into a baptism chancel, and I beckoned my colleagues to follow. Once all of us were inside, he drew shut the curtains and opened his breviary. As he began the rite, Medea unwrapped the devices and laid them on the edge of the benitier. The provost mumbled on and, keeping his eyes fixed on the open book so he wouldn't lose his place, raised and unscrewed a flask of chrism with which he anointed both the staff and the sword.

'In blessing and consecrating these items, I worship the Emperor who is my god, and charge those who bring these items forth that they do so without taint of concupiscence. Do you make that pledge?'

I realised he was looking at me. I raised my head from the kneeling bow I had adopted. Concupiscence. A desire for the forbidden. Did I dare make that vow, knowing what I knew?

'Well?'

'I am without taint, puritus/ I replied.

He nodded and continued with the consecration.

* * *

The first part of my business was done. We went out into the courtyard in front of the cathedral.

'Take these back to the launch and stow them safely,' I told Medea, indicating the swaddled weapons on the cart.

'What's concupiscence?' she asked.

'Don't worry about it,' I said.

'Did you just lie, Gregor?'

'Shut up and go on with you.'

Medea wheeled the cart away through the pilgrim crowds.

'She's a sharp girl, heretic,' Ungish whispered.

'Actually, you can shut up too/ I said.

'I damn well won't/ she snapped. 'This is it/

'What? "It"?'

'In my dreams, I saw you foreswear in front of an Imperial altar. I saw it happen, and my death followed/

I watched the sapfinches spiralling in the air above the yard.

'Deja vu/

'I know deja vu from a dream/ said Ungish sourly. 'I know deja vu from my backside/

'The God-Emperor watches over us/ I reassured her.

'Yes, I know he does/ she said. 'I just think he doesn't like what he sees/

We waited until evening in the yard, buying hot loaves, wraps of diced salad and treacly black caffeine from street vendors. Ungish didn't eat much. Long shadows fell across the yard in the late afternoon light. I voxed Medea. She was safely back aboard the launch, waiting for us.

I was waiting to complete the second of my tasks. This was the appointed day, and the appointed hour was fast approaching. This would be the first test of the twenty communiques I had sent out. One had been to Inquisitor Gladus, a man I admired, and had worked with effectively thirty years before during the P'glao Conspiracy. Orbul Infanta was within his canon. I had written to him, laying out my case and asking for his support. Asking him to meet me here, at this place, at this hour.

It was, like all the messages, a matter of trust. I had only written to men or women I felt were beyond reproach, and who, no matter what they thought of me, might do me the grace of meeting with me to discuss the matter of Quixos. If they rejected me or my intent, that was fine. I didn't expect any of them to turn me in or attempt to capture me.

We waited. I was impatient, edgy… edgy still with the dark mysteries Pontius Glaw had planted in my head. I hadn't slept well in four months. My temper was short.

I expected Gladus to come, or at least send some kind of message. He might be detained or delayed, or caught up in his own noble business. But I didn't think he'd ignore me. I searched the evening crowds for

some trace of his long-haired, bearded form, his grey robes, his barb-capped staff.

'He's not coming/ said Ungish.

'Oh, give it a rest/

'Please, inquisitor, I want to go. My dream…'

Why don't you trust me, Ungish? I will protect you/ I said. I opened my black linen coat so/she could see the laspistol holstered under my left arm.

Why?' she fretted. 'Because you're playing with fire. You've crossed the line/

I balked. Why did you say that?' I asked, hearing Pontius's words loud in my head.

'Because you have, damn you! Heretic! Bloody heretic!'

'Stop it!'

She got to her feet from the courtyard bench unsteadily. Pilgrims were turning to look at the sound of her outburst.

'Heretic!'

'Stop it, Tasaera! Sit down! No one's going to hurt you!'

'Says you, heretic! You've damned us all with your ways! And I'm the one who's going to pay! I saw it in my dream… this place, this hour… your lie at the altar, the circling birds…'

'I didn't lie/ I said, tugging her back down onto the bench.

'He's coming/ she whispered.

Who? Gladus?'

She shook her head. 'Not Gladus. He's never coming. None of them are coming. They've all read your pretty, begging letters and erased them. You're a heretic and they won't begin to deal with you/

'I know the people I've written to, Ungish. None of them would dismiss me so/

She looked round into my face, her head-cage hissing as it adjusted. Her eyes were full of tears.

'I'm so afraid, Eisenhorn. He's coming/

Who is?'

The hunter. That's all my dream showed. A hunter, blank and invisible/

You worry too much. Come with me/

We went back into the Cathedral of Saint Ezra Outlooking, and took seats in the front of the ranks of carrels. Evening sunlight raked sidelong through the windows. The statue of the saint, raised behind the rood screen, looked majestic.

'Better now?' I asked.

Yes/ she snivelled.

I kept glancing around, hoping that Gladus would appear. Straggles of pilgrims were arriving for the evening devotion.

Maybe he wasn't coming. Maybe Ungish was right. Maybe I was more of a pariah than I imagined, even to old friends and colleagues.

Maybe Gladus had read my humble communique and discarded it with a curse. Maybe he had sent it to the arbites… or the Ecclesiarchy… or the Inquisition's Officio of Internal Prosecution.

'Two more minutes/ I assured her. 'Then we'll go.' It was long past the hour I had asked Gladus to meet me.

I looked about again. Pilgrims were by now flooding into the cathedral through the main doors.

There was a gap in the flow, a space where a man should have been. It was quite noticeable, with the pilgrims jostling around it but never entering it.

My eyes widened. In the gap was a glint of energy, like a side-flash from a mirror shield.

'Ungish/1 hissed, reaching for my weapon.

Bolt rounds came screaming down the nave towards me from the gap. Pilgrims shrieked in panic and fled in all directions.

The hunter!' Ungish wailed. 'Blank and invisible!'

He was that. With his mirror shield activated, he was just a heat-haze blur, marked only by the bright flare of his weapon.

Mass panic had seized the cathedral. Pilgrims were trampling other pilgrims in their race to flee.

The backs of the carrels exploded with wicked punctures as the bolt rounds blew through them.

I fired back,

down the aisle, with tidy bursts of las-fire.

Thorn wishes Aegis, craven hounds at the hindmost!'

That was all I was able to send before a bolt round glanced sidelong into my neck and threw me backwards, destroying my vox headset in the process.

I rolled on the marble floor, bleeding all over the place.

'Eisenhorn! Eisenhorn!' Ungish bawled and then screamed in agony.

I saw her thrown back through the panelled wood of the box pews, demolishing them. A bolt round had hit her square in the stomach. Bleeding out, she writhed on the floor amid the wood splinters, wailing and crying.

I tried to crawl across to her as further, heedless bolt-fire fractured the rest of the front pews.

I looked up. Witchfinder Arnaut Tantalid disengaged his mirror shield and gazed down at me.

'You are an accursed heretic, Eisenhorn, and that fact is now proven beyond doubt by the carta issued for you. In the name of the Ministorum of Mankind, I claim your life.'

TWENTTY-ONE

Death at Stezra's. The long hunt. The cellof five.

Precisely how he had found me was a mystery, but I believe he had been on my tail for a long time, since before Cinchare. The fact that he had come to Saint Ezra Outlooking at that hour and that day convinced me that he had intercepted my communique to Gladus. And he might have triumphed over me, right there, right then, if he'd but pressed the advantage and finished the job with his boltgun.

Instead, Tantalid holstered his bolt pistol and drew his ancient chainsword, Theophantus, intent on delivering formal execution with the holy weapon.

I fired my laspistol, powering shot after shot at him, driving him backwards. His gold-chased battle suit, which gave his shrivelled frame the bulk and proportions of a Space Marine, absorbed or deflected the impacts, but the sheer force knocked him back several paces.

I jumped up, firing again, and retreating down the epistle side of the cathedral, towards the feretory. Bystanders and church servants were still fleeing. Its iron teeth singing, Theophantus swung at me. Tantalid was barking out the Accusal of Heresy, verse after verse.

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

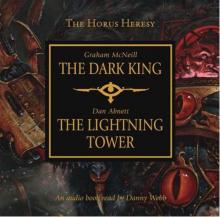

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower