- Home

- Dan Abnett

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 Page 6

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 Read online

Page 6

She also knows that Hesst is a determined individual who takes great pride in his work, and in his duties as a server. Calth’s planetary grid is optimised to run on multi-nodal automatics with a server or servers supplying final approval of all operations. To switch out to automatics alone is to admit the weakness of the fleshbrain. It is to resort to machine alone rather than bioengine synthesis. It is to acknowledge the limits of man, and to submit to the clinical efficiency of cold code.

They have discussed this. They have even discussed it using fleshvoices and vocal chords, unplugged. Hesst has the purest vision of the Mechanicum’s dream, and she adores him for it. It is not, as so many of the unmodified in society believe, the adoration of the machine. It is the use of the machine to extend humanity. It is apotheosis through synthesis. To stand back and allow the machines to do the work is disgusting to Hesst. He probably finds the concept more abhorrent than an unmodified human would.

“It’s not an admission of failure, you know?” she blurts. She is resuming a conversation they were having two days before, as if no intervening time had elapsed.

He acknowledges the fact, recognising the conversational marker appended to her code that reopens his saved file of that exchange.

“It is, in fact, a practice recommended by Mars.”

Hesst nods.

”If we build systems we cannot run, what is the point of building them? Tell me where that leads, Magos Tawren? ”

”The annihilation of self. The abnegation of sentience. ”

‘Exactly,’ says Hesst. His use of fleshvoice surprises her, but she instantly realises that he has switched from binaric in order to make a symbolic point. This amuses her, and she shows him that she is amused by using a facial expression.

‘You think this is about my pride, don’t you, Meer?’ he asks.

She shrugs. Like him, she is still, simultaneously, making subtle haptic gestures and scouring the noosphere’s dataflow. ‘I think that no one, not even an adept of the rank server or above, has ever run an operation like this on discretionary mode alone. I think you’re attempting some kind of record. Or trying to win a medal. Or trying to rupture a major organ.’

Her voice is clean, as pure as code. He sometimes wishes she would use it more.

‘It is simply a question of security and efficiency,’ he says. ‘The grid is designed to be multi-nodal. That is its strength. It has no single heart, no single brain. It is global. Take out any point, even this Watchtower, even me, and any other ranking server or magos can take over. The grid will adjust and recognise the discretion of the next in line. This tower could topple, and a server on the far side of the planet would instantly take over. Multi-nodal redundancy is a perfect system. You cannot kill anything that has no centre. So I’d prefer not to weaken the integrity of this planet’s defence system even slightly by opting out of discretion and transferring approval oversight to the orbital engines.’

‘This conjunction is expected to continue for another day or two,’ she remarks. ‘When would you like me to take over from you? Before or after you stroke out and tumble to the floor?’

Tawren realises he isn’t listening. He has become preoccupied with the inload.

‘What is it?’ she asks.

‘Scrapcode.’

Any complex information system will produce scrapcode as a result of internal degradation. She knows that. She wonders what he means, and peers into the manifold.

She sees the scrapcode, dull amber threads of diseased information buried in the mass of healthy data. There is two per cent more of it than any Analyticae projection has calculated for the Calth noosphere, even under the irregular circumstances of the day. That is an unacceptable margin.

”Filtration isn’t clearing it. I don’t know where it’s coming from. ”

He has reverted to binaric blurt. There is no time for words.

[mark: -15.02.48]

Criol Fowst has been given a blade, but it proves impractical to use it. He uses his sidearm instead. The oblators need to be killed cleanly and quickly. There isn’t time to fool about with a knife.

Outside the shelter, his appointed officers are rousing the men in song. Chanting fills the air. They have been encouraged to bring viols and qatars, tambours, pipes, horns and bells. It is supposed to sound like a celebration. The eve of battle, honoured allies, the anticipation of glory, all of that nonsense. It is supposed to sound joyous.

And it does, but Fowst can hear the ritual theme inside the noisy singing. He can hear it because he knows it’s buried there. Old words. Words that were old before humans learned to speak. Potent words. You can set them to any tune, to the verse-and-chorus of an Army battle reel. They work just the same.

The singing is loud. It’s quite a commotion, six thousand men in this corner of the muster fields alone. Loud enough to drown out his shots.

He pulls the trigger.

The matt-grey autopistol barks, bucks in his hand, and slams a single round through the temple it’s pressed against. Blood and tissue spray, splashing his jacket. The kneeling man flops sideways, as if the weight of his punctured head is pulling him down. There’s a whiff of fycelene in the air, a smell of powdered blood, burned flesh and blood vapour.

Fowst looks down at the man he has just shot and murmurs a blessing, the sort one might offer to a traveller embarking on a long and difficult voyage. His mercy almost came too late that time. The man’s eyes had begun to melt.

Fowst nods, and two of his appointed officers step forward to drag the body aside. Now the corpses of seven oblators lie on the groundsheet spread out to one side.

The next man steps up, stone-faced, unfazed at the prospect of imminent death. Fowst embraces him and kisses his cheeks and lips.

Then he steps back.

The man, like the seven who have come before him, knows what to do. He has prepared. He has stripped down to his undershirt and breeches. He’s given everything else away, even his boots. The Brotherhood of the Knife uses whatever equipment it can gather or forage: hauberks, body armour, ballistic cloth, sometimes a little chainmesh. There’s usually a coat or cloak or robe over the top to keep out the weather, always dark grey or black. With no more need for any field gear, the man has given away his good coat, his gloves and his armour to those who can use them later. His weapons too.

He’s holding his bottle.

In his case, it’s a blue glass drinking bottle with a stoppered cap. His oblation floats inside it. The man before him used a canteen. The man before that, a hydration pack from a medicae’s kit.

He opens it and pours the water out through his fingers so the slip of paper inside is carried out into his palm. The moment it’s out of suspension in the hydrolytic fluid, the moment it comes into contact with the air, it starts to warm up. The edges begin to smoulder.

The man drops the bottle, steps forward and kneels in front of the vox-caster. The key pad is ready.

He looks at the slip of paper, shivering as he reads the characters inscribed upon it. A thin wisp of white smoke is beginning to curl off the edge of the slip.

His hand trembling, the man begins to enter the word into the caster’s pad, one letter at a time. It is a name. Like the seven that have been typed in before, it can be written in human letters. It can be written in any language system, just as it can be sung to any tune.

Criol Fowst is a very intelligent man. He is one of a very few members of the Brotherhood who have actively come looking for this moment. He was born and raised on Terra to an affluent family of merchants, and pursued their interests into the stars. He’d always been hungry for something: he thought it was wealth and success. Then he thought it was learning. Then he realised that learning was just another mechanism for the acquisition of power.

He’d been living on Mars when he was approached and recruited by the Cognitae. At least, that’s what they thought they’d done.

Fowst knew about the Cognitae. He’d made a particular study of occult orders, secre

t societies, hermetic cabals of mysteries and guarded thought. Most of them were old, Strife-age or earlier. Most were myths, and most of the remainder charlatans. He’d come to Mars looking for the Illuminated, but they turned out to be a complete fabrication. The Cognitae, however, actually existed. He asked too many questions and toured datavendors looking for too many restricted works. He made them notice him.

If the Cognitae had ever been a real order, these men were not it. At best, they were some distant bastard cousin of the true bloodline. But they knew things he did not, and he was content to learn from them and tolerate their theatrical rituals and pompous rites of secrecy.

Ten months later, in possession of several priceless volumes of transgressive thought that had previously been the property of the Cognitae, Fowst took passage rimwards. The Cognitae did not pursue him to recover their property, because he had made sure that they would not be capable of doing so. The bodies, dumped into the heat vent of the hive reactor at Korata Mons, were never recovered.

Fowst went out into the interdicted sectors where the ‘Great Crusade’ was still being waged, away from the safety of compliant systems. He headed for the Holy Worlds where the majestic XVII Legion, the Word Bearers, were actively recruiting volunteer armies from the conquered systems.

Fowst was especially intrigued by the Word Bearers. He was intrigued by their singular vision. Though they were one of the eighteen, one of the Legiones Astartes, and thus a core part of the Imperium’s infrastructure, they alone seemed to exhibit a spiritual zeal.

The Imperial truth was, in Fowst’s opinion, a lie. The Palace of Terra doggedly enforced a vision of the galaxy that was rational and pragmatic, yet any fool could see that the Emperor relied upon aspects of reality that were decidedly unrational. The mind-gifted, for example. The empyrean. Only the Word Bearers seemed to acknowledge that these things were more than just useful anomalies. They were proof of a greater and denied mystery. They were evidence of some transcendent reality beyond reality, of some divinity, perhaps. All of the Legiones Astartes were founded on unshakeable faith, but only the Word Bearers placed their belief in the divine. They worshipped the Emperor as an aspect of some greater power.

Fowst agreed with them in every detail except one. The universe contained beings worthy of adoration and worship. The Emperor, for all his ability, simply wasn’t one of them.

On Zwanan, in the Veil of Aquare, a Holy World still dark with the smoke of Word Bearers compliance, Criol Fowst joined the Brotherhood of the Knife, and began his service to the XVII primarch.

He was able. He had been educated on Terra. He was no heathen backworlder energised by crude fanaticism. He rose quickly, from rank and file to appointed officer, from that to overseer, from that to his current position as a confided lieutenant. The name for this is majir. His sponsor and superior is a Word Bearers legionary called Arune Xen and, through him, Fowst has been honoured with several private audiences with Argel Tal of the Gal Vorbak. He has attended ministries, and listened to Argel Tal speak.

Xen has given Fowst his ritual blade. It is an athame blessed by the Dark Apostles. It is the most beautiful thing he has ever owned. When he holds it in his hand, byblow gods hiss at him from the shadows.

The Brotherhood of the Knife is not so-called because it favours bladework in combat. The name is not literal. In the dialect of the Holy Worlds, the Brotherhood is the Ushmetar Kaul, the ‘sharp edge by which false reality might be slit and pulled away to reveal god’.

Fowst’s attention has wavered. The oblator has finished keying in the eighth name. The slip of paper is burning in his hand. Smoking scads are falling from his fingers. He is shaking, trying not to scream. His eyes have cooked in their sockets.

Fowst remembers himself. He raises the sidearm to deliver mercy, but its clip is empty. He tosses it away, and uses the athame that Battle-brother Xen gifted him.

It is a messier mercy.

Eight names are now in the system. Eight names broadcast into the dataflow of the Imperial communications network. No filter or noospheric barrier will block them or erase them, because they are only composed of regular characters. They are not toxic code. They are not viral data. But once they are inside the system, and especially once they have been read and absorbed by the Mechanicum’s noosphere, they will grow. They will become what they are. They will stop being combinations of letters, and they will become meanings.

Caustic. Infectious. Indelible.

There are eight of them. The sacred number. The Octed.

And there can be more. Eight times eight times eightfold eight…

Majir Fowst steps back, wipes blood from his face, and welcomes the next man up to the vox-caster with a kiss.

[mark: -14.22.39]

Still over twelve hours out of Calth orbitspace, the fleet tender Campanile performs a series of course corrections, and begins the final phase of its planetary approach.

7

[mark: -13.00.01]

‘I can assure you, sir,’ says Seneschal Arbute, ‘the labour guilds are fully aware of the importance of this undertaking.’

She’s a surprisingly young woman, plain and businesslike. Her robes are grey.

Sergeant Selaton revises his estimate. What would he know? She’s not so much plain, just unadorned. No cosmetics, no jewellery. Hair cropped short. In his experience, high status females tended to be rather more decorative.

They have accompanied her from the Holophusikon to the port, following her official carrier in their speeder. She is a member of the Legislature’s trade committee. Darial and Eterwin have more power, but both insist that Arbute has a much more effective relationship with the guild rank and file. Her father was a cargo porter.

The port district is loud and busy. Huge semi-auto hoists and cranes, some of them looking like quadruped Titans, are transferring cargo stacks to the giant bulk lifters on the field.

Captain Ventanus seems to have wearied of the effort. He stands to one side, watching the small fliers and messenger craft zip across the port like dragonflies over a pond. He leaves Selaton to do the talking.

‘With respect,’ says Selaton, ‘the guildsmen and porters are falling behind the agreed schedule. We’re beginning to get back-up in the mustering areas.’

‘Is this an official complaint?’ she asks.

‘No,’ he replies. ‘But it has been handed down from the primarch. If you can put in any kind of word, my captain would appreciate it. He’s under pressure.’

She smiles quickly.

‘We’re all under pressure, sergeant. The guilds have never undertaken a materiel load on this scale. The estimated schedule was as accurate as they could make it, but it is still an estimation. The porting crew and loaders are bound to hit unexpected delays.’

‘Still,’ says Selaton. ‘A word to their foremen. From a member of the city legislature. A little encouragement, and an acknowledgement of their effort.’

‘Just so I know, what is the shortfall?’ asks Arbute.

‘When we came looking for you, six minutes,’ he says.

‘Is that a joke?’

‘No.’

‘Six minutes is… Forgive me, sergeant. Six minutes is nothing. It’s not even a margin of error. You came to find me, and dragged me here from the Holophusikon ceremonies because of a six-minute lag?’

‘It’s twenty-nine minutes now,’ replies Selaton. ‘I do not wish to sound rude, seneschal, but this is a Legion-led operation. The tolerances are tighter than in commercial or regular military circumstances. Twenty-nine minutes is bordering on the abominable.’

‘I’ll talk to the foremen,’ she says. ‘I’ll see if there’s any reserve they can draw on. There has been bad weather.’

‘I know.’

‘And some incidence of system failure. Junk information. Corrupt data.’

‘That happens too. I’m sure you will do what you can.’

She looks at him, and nods.

‘Wait here,’ she says.

[mark: -11.16.21]

‘In your considered opinion?’ Guilliman asks.

Magos Pelot is the senior serving Mechanicum representative aboard the flagship Macragge’s Honour, and he’s just been required to present the primarch with awkward news. He thinks for a moment before replying. He does not want to tar his institution with verdicts of incompetence, but he has also served the primarch long enough to know that little good ever comes of sugaring the pill.

‘The scrapcode problem we have identified is a hindrance, sir,’ he says. ‘It is regrettable. Especially on a day like today. These things do happen. I won’t pretend they don’t. Natural degradation. Code errors. They can occur without warning for any number of reasons. The Mechanicum dearly wishes we weren’t being plagued by them during this event.’

‘Cause?’

‘Perhaps the sheer scale of the conjunction itself? Precisely because today is important. The simple mass of data–’

‘Is it proportional?’ asks Guilliman. ‘Is it the proportional increment you would naturally expect to find?’

Magos Pelot hesitates. His mechadendrite implants ripple.

‘It is slightly higher. Very slightly.’

‘So it’s an abnormal level, in the experience of the Mechanicum? It’s not natural degradation?’

‘Technically,’ Pelot agrees. ‘But not in any way that should be deemed alarming.’

Guilliman smiles to himself.

‘So this is just… for my information?’

‘It would have been inappropriate not to inform you, lord.’

‘What are the implications, magos?’

‘The Server of Instrumentation insists he can continue to oversee the operation, but the Mechanicum believes his attention would be better spent identifying and eradicating this scrapcode problem before it develops any further. For the duration of that activity, the server would suspend discretion, and oversight would be managed automatically by the data-engines in the orbital yard hub.’

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

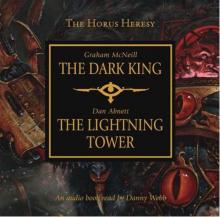

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower