- Home

- Dan Abnett

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor Page 5

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor Read online

Page 5

‘That’s good,’ said the Secretary.

‘But,’ I added, ‘it is better to know, to be prepared. Is there a reason you didn’t tell me?’

‘Only a concern that an awareness could betray you,’ the Secretary replied. He took up his tiny thimble cup daintily and sipped from it. ‘You might overcompensate, be over-wary, and thus give yourself away.’

I understood, though I was disappointed that the Secretary imagined me to be that clumsy.

‘What kind of danger might the Blackwards represent?’ I asked.

‘None at all,’ said Judika. ‘The Blackwards are nothing. But if they are guilty of the crimes we suspect, then they will have contacts.’

‘Beta,’ said the Secretary, ‘we suspect that a significant heretic society is operating in Queen Mab. It is likely they are procuring certain relics through the Blackwards, or have the Blackwards on a retainer to perform such work. It is likely they have inveigled influence at many levels of the city’s social structure. And it is possible they have detected the existence of the Maze Undue.’

‘Oh,’ I said.

‘For the school to function, it must remain secret,’ said Judika. ‘If the Maze Undue has been detected, we must act to identify and eliminate the threat, or else pack up and move the school.’

‘To another part of the city?’ I asked, aghast.

The Secretary and Judika glanced at one another.

‘To another world,’ replied the Secretary.

‘If the Maze Undue is compromised,’ said Judika, ‘it will be necessary. The training and preparation of agents such as you is too valuable to the Holy Ordos to be put at risk.’

‘So what must happen?’ I asked.

‘We will carry on for now,’ said the Secretary. ‘Judika has been sent by the Ordos, may the Throne bless him, to review the situation. He will watch over us, and assess if we are at risk.’

‘With luck, I might be able to smoke out and sanction this menace,’ said Judika.

‘Judika will be our guardian angel for a while,’ said the Secretary. He cleared his throat. Static prickled.

‘So, tomorrow?’ I asked.

‘Go back,’ said the Secretary. ‘Continue with your function. All functions must continue for now. You are not the only pupil engaged in something that is more than an exercise.’

‘In the evening, when you return,’ said Judika, ‘perhaps you could brief me and the Secretary personally? We’ll do that daily, just for now. Ebon will be waiting for you.’

‘Of course,’ I said. I was slightly dumbfounded, because he had just referred to the Secretary by his name, his forename no less, as if they were old friends or equals.

‘Well, you need a good night’s rest,’ said the Secretary. ‘Is there anything else you want to ask us before you go to dinner and then retire?’

‘Yes, Secretary,’ I said. ‘Is it the Cognitae?’

CHAPTER 9

Of apprehension

They both stared at me.

‘You said a word then,’ began the Secretary. ‘Beta, what was it, the word you used?’

‘The word was Cognitae, sir,’ I replied.

‘And why… why would you use that word, Beta?’ he asked.

‘It is a deduction, sir,’ I said plainly. ‘A heretic society, of influence and power. This is what I understand the Cognitae to be. So I asked the question.’

‘When did you ever hear such a word?’ asked Judika stiffly.

‘Last year,’ I replied. I didn’t much like his tone. It seemed as though he was preparing to scold me. The Secretary could scold me. Any of the mentors could, except perhaps Murlees, who frankly did not have it in him to be harsh. But Judika Sowl could not. Not even if he were a high and mighty interrogator these days.

I looked at the Secretary.

‘When the man broke in last year, and attacked Mentor Saur. He said the word before he died. Mentor Saur told me it was the name of a damnable and black society. I told all this to Mam Mordaunt.’

‘She did,’ the Secretary told Judika, ‘she did indeed. It was an unpleasant incident, which we had hoped would be isolated.’

He looked back at me. He cleared his throat, but still the static would not clear away.

‘Beta,’ he said carefully, ‘I do not believe that either Thaddeus or Mam Mordaunt told you very much about the Cognitae at all. Yet you presume–’

‘It was a deduction, sir,’ I said. ‘I simply made a deduction, and connected the few facts I knew. Was it wrong of me to speculate? Was it wrong of me to ask?’

‘Not at all,’ said the Secretary. ‘I think it’s very fine that you did. It proves that you are among our very best, and that your temper is of the finest quality.’

I saw that Judika was watching me very carefully. I don’t think he liked hearing me complimented in this way. I had once found those eyes so very appealing, but now they seemed dark and hard, like the copper coins they place on the eyes of the dead down at the Feygate Charnel.

‘Do not mention the word, or the idea, to anyone,’ the Secretary told me. ‘I will prepare some notes for you, personally, that we can review tomorrow. A few pointers.’

‘Thank you, sir,’ I said.

‘You know that the Cognitae impersonate, don’t you?’ asked Judika.

‘Yes.’

‘They act to effect infiltration, and they are trained in methods very similar to the ones we hone here at the Maze Undue.’

‘That is how it seems to me,’ I agreed, ‘and they impersonate even servants of the Holy Ordos.’

‘They do,’ replied Judika. ‘So be on your guard. If anyone confronts you, and shows you a rosette to prove his or her authority, do not believe it.’

‘I will not,’ I assured him.

‘What should I do instead?’ I asked the Secretary as an afterthought.

The Secretary hesitated, so Judika answered me instead.

‘Kill them,’ he said.

I had little appetite for the evening meal. I picked at it. No one seemed to notice, because the Secretary came in, and brought Judika to show to everyone. Faria, Corlam, Byzanti (who was, by that time, returned for the day) and Maphrodite had all known him in the old days, and they leapt up to greet him, and quizzed him incessantly. He laughed, and answered their prattle evasively.

Through it all, he kept looking past them at me. His eyes were still hard, like the coins of the dead.

I went off to my room to sleep. From the refectory, I heard laughter and voices, and later, a viol and tambor.

Later still, the Maze Undue was silent.

I woke, in the pitch darkness of night’s deepest part. The house had gone to sleep, and the lights had been put out. I had fallen asleep in my cot, over the book I had been reading, and my lamp had burned out. I had been dreaming. In the dream, I had seen endless dusty shelves lined with bric-a-brac, a piece of dream that I presumed had been inspired by my visit to the Blackwards emporium. I fancy that, at some point, the dolls from the shop window turned up too, and spoke to me, or rather made silent clacks of their wooden mouth-mechanisms. I felt eyes watching me as well, throughout the dream. I did not see the face the eyes belonged to, but they seemed as hard as copper coins, so I presumed they belonged to Judika Sowl.

I should say, for the record, that I set no store by the content of dreams. I have yet to be convinced by the work of dreamreaders and oneirocriticks, and have little belief in the prophetic nature of dreams, even though the Good and the Great of Mankind’s Imperium have often been led by clear and precise dream visions down through history.

Dreams haven’t, in my experience, had any authentic currency, and I mistrust those who fancy otherwise. Dreams are too ephemeral, too flimsy. They are simply the events of the day, disjointed and lent odd emphasis by our resting minds, and then swirled about like leaf-litter in an autumn breeze so that they seem to possess a life of their own, and seem to shuffle into some cryptic meaning.

Dreams are simply our minds restin

g, and saving to memory recent happenings and sights. They are like a system reset, I think, for the human mind. They have no purpose, and carry no weight.

Nevertheless, they can be unsettling.

I awoke in the dark, and felt, with a false certainty that dreaming can reinforce, that the eyes were still upon me.

It was the most curious feeling. I lay still for a moment, imagining it to be my dream lingering. I felt that it would shortly dispel, as all dreams do.

But it did not. I felt that I was not alone, or rather that there was, in the Maze Undue, some intrusive presence, a force, some malign entity that had got in while we slumbered and was spying on us all.

I got out of bed and pulled on some clothes, the nearest that were to hand in the darkness. It was cold, distinctly cold. Given the high position of the Maze Undue, it was often cold during the night, when the winds off the Mountains assailed Highgate Hill, but this cold was peculiar.

I struck a match, not to ignite my lamp and gain light, but to hold up a flame. It flickered and bent.

It was as I thought. The Maze Undue was old, and it had significant character and idiosyncrasies. Live in a place like this long enough, and you come to know them. I knew that in my room, a flame would only stir in a breeze if the breeze was coming up along the hall from the west end of the landing, and that the only way a breeze like that could occur was if the lower stair door had been left open.

I shook out the match. I pulled on my boots and stepped out into the hallway, pulling the door of my room closed behind me.

It was dark, but my eyes adjusted. Some little starlight was seeping in through the skylights and smudged window panes, and certain shapes had a silver outline. The rest was blue-black darkness. I could plainly feel the breeze now, gentle but distinct.

I was sure that no one had intruded. Someone had merely left a door unlatched down below. The Maze Undue was soundly guarded by wards and charms, by sensors, by motion detectors and by tripwires, especially in the ragged hem of the skirts. It was not a place that someone could simply break into undetected.

Except the man in the drill, the ruthless Cognitae agent, he had broken in.

I steadied myself. The key word was undetected. If someone had broken in, the alarms would have been tripped. The Cognitae assassin had broken in, but Mentor Saur had discovered him before he could penetrate beyond the drill.

I reached the stairs. Looking down over the banister rail into the deep, tight, long drop of the wooden staircase, I could see very little. I had expected to see a pale cast of light coming in through the open door below. There was no light. I felt the breeze again, against my cheek.

I crept down, all six flights, to the lower stair door. I made no sound. I knew which of the old, worn steps to avoid because they groaned or complained under a weight, and I knew exactly where to place my feet on others, so as to prevent them from creaking.

I reached the lower stair door. There was no cast of light at the foot of the stairs because the door was not open, not even ajar. It was shut, and bolted from my side, the inside. There was no breeze. Not even the slightest cold gust slid like a knife around the edges of the door.

I started back up the stairs again. I confess that I was experiencing a little anxiety. My solid, rational explanation had been disproved.

I went back up the stairs. Halfway up the six flights, I misstepped and made a stair creak. I froze. I waited. Nothing moved. Nothing else made a sound. I breathed out, and mentally scolded myself. Anxiety had made me careless, and had forced an error out of me. Anxiety engendered haste, Mentor Saur always taught us, and haste breeds carelessness. Carelessness is your enemy. Carelessness is not big or strong, nor even menacing, but he is an enemy that will kill you quick enough. Knowledge, for the other part, is an ally. Use knowledge, and he will guard and repay you. Do not allow Carelessness to make you turn your back on Knowledge, not even for a instant.

I knew the house. I knew the Maze Undue in intimate detail, and that was my ally, my Knowledge. But here was treacherous Carelessness forcing me to ignore that Knowledge and step upon a wooden stair that would betray me.

I reprimanded myself, and resumed my ascent with greater confidence and determination.

Back on the landing where I had begun my descent, on my own hallway, I stood for a moment. I felt the breeze again, quite distinctly. It could not be coming from below, that I had established.

There was only one other possibility. It was coming from above.

Now, above my hall the staircase leads onto landings and ladders, and a cluster of disused attics. We didn’t go up there, because the floors were rotten and unsafe, and so I had not considered it. But if an attic window had swung open, or a section of old slate work fallen away, that would explain the breeze.

I went up. The stairs took me to the next landing. Then a ladder gave me access to the roof-hole, and I pulled myself up into the attics. It was dusty, fearsomely dusty: as dusty, I fancied, as the legendary City of Dust, said to lie out in the Sunderland. I wanted to cough, but I kept the dry tickle under control.

The attics were spaces of beams and rafters, of platforms and planked shelves, of stone walls with old windows, which had been internal for centuries after some conversion or extension, but which served now as doors into other compartments. The ceilings were low in some places, and towering in others, slopes of tiled skin and wooden rib. Cobwebs drifted like smoke.

We had come up as children, when the attics were a place of escape and recreation. The ceiling of the fourth hall had fallen in after heavy rains, and after that we were forbidden. I remembered it, though, every turn and nook. I saw places where we had scratched our names on beams or slates or brick. Many names. The names of pupils who had been forgotten long before I ever came into the Maze Undue. Here, still, was a doll, a little pale thing with a china face, that some pupil had set upon a cross-tie years ago and had never come back for. We had found it during our explorations, thick with dust, but had not dared to touch or move it. It belonged here. As I saw it that night, with more adult eyes, I felt it had not been so much set down and forgotten, as deliberately placed, as if this cross-tie was its new station in life, a seat from which it should watch and guard.

In another place, I found a small glass beaker that we had left there eight or nine years before. We had gone hunting spiders, and the beaker was to cup over them. But we had found none, though the roofspace was thick with cobwebs. The beaker had been put down and never collected.

A breath of wind stirred through the attics. I moved ahead, and found that an old, boarded partition had been removed, a partition that stoppered one of the places where the Scholam Orbus and the Maze Undue wound into one another. Was it the work of children, coming up through the orphanage, taking down boards to explore? We had done just that, when we had been the children of the orphanage.

I half-expected to hear the laughter of a child, distant and stifled, tinkling back through the attic gloom, from hiding places. From the past.

And I did.

Writing the words here, just recalling it, I still feel the sharp, quick temperature drop of fear. It was not the most frightening thing that had ever happened to me, but it was close; it would make a shortlist of the very most frightening. The nature of it, in particular, the unexceptional fact of it, made it worse. An everyday sound, rendered uncanny by the situation, and delivered on cue.

I told myself it was simply my fancy. I reassured myself that it was self-suggestion. I had been thinking of it, and my imagination had supplied the rest.

Then I laughed out loud, realising that an instant of fear had deprived me of my sensible faculties. I had barely considered the simplest and most logical explanation: it was children. It was children from next door, sneaking in and exploring after dark.

I clambered over a low beam, dislodging decades of dust like talcum powder, and entered the next part of the roofspace world, homing in, as I thought, on the laughter I had heard.

But through the

space, across the next boarded floor of the attic, no dust was disturbed. I was lithe enough, and I had not been able to move without swirling the stuff around. If children were here, even small children, there would be footprints on the boards.

Then, just ahead through the beams and cross-ties, I glimpsed something move. Something white… spectral, as it seemed to me.

I moved forwards. It did not hear me at first. Then it turned, and found me facing it.

‘What are you doing here?’ I asked Sister Tharpe. ‘And how have you left no footprints in the dust?’

CHAPTER 10

Which concerns a desperate struggle

Sister Tharpe stared at me, her green eyes like the active lights of a weapon visor.

‘I did not hear you,’ she said. Surprise had taken even more of the fake Zuskite accent out of her voice.

‘You were not supposed to,’ I replied.

She composed herself. She was in her sorority’s robes, and her starched headdress had caught the starlight, making the whiteness I had glimpsed.

‘Beta, isn’t it?’ she asked.

She knew full well. Even in the low light, I could read her face: surprise, the awkwardness of being caught, and by me especially. She was trying to hide all of that, of course.

‘Sister Tharpe,’ I said firmly. ‘What are you doing here?’

She shrugged.

‘I confess, I could not sleep,’ she said. ‘I am new here, new to the scholam. I could not settle, even when all the children were soundly off. I thought I would look around, explore. I thought the activity might calm me and, may the Emperor protect, tire me enough for slumber.’

‘You are not in the scholam,’ I said. ‘You are in the Maze Undue.’

‘Am I?’ she said. ‘I had no notion.’

A lie. Easy to spot, from tone alone.

‘You must have known,’ I said. ‘You took away boards and came through a wall space that had been shut up.’

‘I didn’t realise, Beta,’ she said.

She used my name. An interesting ploy, meant to diffuse the tension. I wasn’t having it. I was fairly sure I knew what she was, and I was fast regretting not arming myself before leaving my room. I remembered Judika’s surprising words. But how does one arm oneself to kill a nun?

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

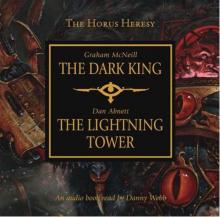

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower