- Home

- Dan Abnett

Ravenor Omnibus Page 46

Ravenor Omnibus Read online

Page 46

Tchaikov moaned, twitching.

Nayl bolstered his weapon and walked over to her. He squeezed his gunshot left arm with his right hand and spattered blood onto the ground. The sword writhed and turned, scenting a fresh victim. It slithered towards Nayl.

He squeezed his wound harder and more blood spurted out. That was too much for the sword. It flew at him.

He side-stepped, and caught it by the hilt as it flew by. As soon as it was in his hand, he wrenched round violently and swung it down into the deck.

It took three, savage blows before the blade finally shattered. By then, the deck was deeply gouged. The blade wailed as it died.

Nayl threw the broken hilt away. He walked over to Tchaikov.

‘The key, please,’ he said.

‘Never!’ she hissed.

‘You’re bleeding out fast, mamzel,’ he noted.

‘Then I will die,’ she replied, her rapid breath wafting her molidiscu mask.

‘Doesn’t have to be that way,’ Nayl said.

‘What? Are you proposing to save me? Spare me? Get me to the medicaes?’

Nayl shook his head. He reloaded his handgun and aimed it at her right temple. ‘My offer is to make it quick. One brief instant of pain compared to a slow, lingering death.’

Tchaikov gasped. ‘You are a man of honour, sir. I thank you. The key is five-two-eight six-five.’

‘And thank you,’ Nayl said. He rose and began to walk away.

‘I gave you the key!’ Tchaikov cried. ‘Now do as you promised! Finish me!’

Nayl continued to walk.

‘All right! All right!’ Tchaikov called. ‘Five-eight-two six-five! That’s the key! The real key! I lied before, but that’s the real truth! Now kill me! End this pain! Please!’

Nayl kept walking. ‘Still going to check,’ he said.

EIGHT

WYSTAN FRAUKA HEARD the low warble of the detector alarm. He shot a look at Zael and put a finger to his lips, then he got up, took a chromed autosnub from his jacket pocket, and went over to the portable vox.

He pushed the set’s ‘active’ key.

‘Yes?’

‘It’s us. Screen down, pop the locks and let us in.’

Frauka turned to the portable console nearby which controlled the security screens Harlon had set up around Miserimus House and deactivated them. He also turned the auto-locks.

‘Clear,’ he said into the vox.

A minute or two later the five figures came tramping up the stairs. Zeph Mathuin led the way, followed by Thonius, who was carrying some kind of glass box.

‘How did it go?’ Frauka asked Mathuin, knowing full well that it wouldn’t be Mathuin who replied. Ravenor’s dormant chair sat in the corner of the room where Frauka had been keeping company through the evening with Zael.

‘Badly,’ said Ravenor in Mathuin’s voice. ‘We got what we needed, but it turned into a bloodbath.’

Zael had got to his feet, and was now staring wide-eyed at the returners. Nayl had a messy wound in the arm, and he was half-carrying Kara, who looked pale and ill.

‘This is beyond our basic medical ability,’ said Ravenor. ‘We’re going to need a physician. Someone who won’t ask questions.’

‘I’ll go find one,’ said Kys grimly.

‘I know where to find one,’ said Zael. They all looked at him. ‘I come from here, remember? I know a guy.’

‘Very well,’ said Kys to the boy. ‘You’re with me.’

They hurried out. Nayl took Kara to one of the bedrooms and made her comfortable.

‘Carl, get to work deciphering the contents of the box,’ Ravenor said. ‘Oh, and check on Skoh too, please.’

Thonius nodded and hurried away with his prize.

Ravenor sat Mathuin’s body down in a battered armchair.

‘Not a good night then?’ Frauka said.

‘Tchaikov’s security was on a hair trigger. The moment they thought something was wrong, they just went off. It was bloody. We ended up torching the place to cover our tracks.’

‘You burned it down?’ Frauka asked laconically, lighting a lho-stick.

‘There were a lot of bodies,’ Ravenor said. ‘The longer it takes anyone to figure out what happened, the better. Tchaikov was a powerful underworld figure. From the mess we left, people will suspect she ran foul of a rival operation.’

Mathuin sighed. Ravenor had just released him. He blinked and looked up at Frauka.

‘Hey, Wyst,’ he said. He got to his feet. ‘I’m hungry,’ he muttered, and left the room.

The support chair hummed and swung around, prowling across the room towards Frauka.

‘So Nayl took a bullet?’ Frauka said. ‘What happened to the redhead?’

‘Some kind of warped blade.’

‘All in a night’s work.’

‘I suppose so. I’m going to check on her, then I’d better help Thonius unravel the data.’

‘Uh, before you go…’ Frauka began.

‘Yes, Wystan?’

While you were all gone, the boy seemed to get a bit edgy. So I stayed with him, just chatting, you know.’

‘Improving your people skills?’

‘Whatever,’ Frauka took a drag on his lho-stick. He seemed uncomfortable, as if not sure how to say something. ‘We talked about this and that, his past, growing up here. I think coming back to Eustis Majoris has woken up some memories. He was telling me about his granna, and his sister.’

‘Well, I’m glad he was able to confide in y—’

Frauka held up a hand and waved it gently. ‘No, it’s not that. Do you know what his name is?’

‘Of course,’ Ravenor replied. ‘It’s Zael Efferneti. One of the first things he told me.’

‘Yeah,’ said Frauka. ‘Efferneti. His father’s family name. But in our little chat tonight, it just slipped out that Zael’s ma and pa never actually applied for a marriage licence from the state.’

‘So he was born out of wedlock. So what?’

‘Well, just as a technicality, that would mean his surname should actually be his mother’s family name, not his father’s, the one he adopted. Right?’

‘Right. But it is just a technicality. Why do you think that’s important?’

‘Because it turns out his mother’s family name,’ said Wystan Frauka, ‘was Sleet.’

THONIUS UNLOCKED THE door and looked in. Skoh sat on the chair. The hunter slowly turned his head and looked at Carl.

‘Food?’ he asked.

‘We’re a little busy. We’ll get to it.’

Skoh raised his manacled hands slightly. ‘Getting cramp in my wrists again. Bad cramp.’

‘All right,’ said Carl with a sigh. He walked into the room until he was just beyond the reach of the floor chain. ‘Show me.’

Skoh raised his hands, to show that both of the heavy steel manacles were locked tight around his wrists.

Carl nodded, took the key from his pocket and tossed it to Skoh. The hunter caught it neatly, unlocked his manacles, and growled with relief. He nursed and rubbed his wrists, flexing them and stretching them out. ‘Hell, that’s better.’

‘That’s enough,’ said Carl.

Skoh finished his stretching, and locked the manacles in place again. He tossed the key back to Carl.

‘Show me.’

Skoh repeated his gesture, raising his hands so that Carl could clearly see the manacles were tight and secure.

Carl walked out of the room, and locked the door behind him. His right hand was shaking again. The raid at Tchaikov’s had been a real adrenaline rush, a real ride. He’d done well, he’d got what Ravenor needed. But Skoh had brought him down hard. Something about the hunter freaked Thonius out, even when he was locked up.

Carl had a sour taste in his mouth and his heart was knocking. He knew he had to get back downstairs and start work on the riddle box. But he wanted to smooth his wits out first.

He went into bathroom, pulled the bolt on the door, and took the parcel

of red tissue paper out of his pocket.

THEY RODE ONE of the sink-level trains across the eastern quadrant of the city, and climbed off in a filthy substation that the signs said was in Formal J.

‘This is where you grew up,’ Patience said. Zael nodded.

‘I’m sure I could have found a doctor closer to the house.’

‘We need the right sort of doctor,’ Zael said. ‘The right sort, yeah? I mean one who won’t ask questions or anything.’

Patience couldn’t argue with that.

‘Well, there was a guy in my hab neighbourhood. We called him the Locum. I think he’s what you want.’

Hot, dirty winds scorched up the transit tunnels as other clattering trains approached. Zael led Patience up the iron stairs into the dark dripping sinks of Formal J.

It was not a good part of town. So much trash and acid wash had accumulated in the lower sinks, most foot traffic came and went on the higher walkways between the crumbling hab-stacks. They passed a few rowdy bars and dining houses, bright with lights and drunken noise, but for the most part it was a slum city, full of poverty-trapped souls who lingered in the doorways of their ratty habs, or sat on the front steps of stacks, passing around bottles without labels. The street air reeked of acid and urine. It reminded Patience a little of Urbitane, the hive stack on Sameter where she’d grown up. But there had been a spark of urgency there, a sense of life fighting to catch a break amid the squalor. Here, it felt like people had just given up all hope.

They walked for twenty more minutes, into a network of dark lanes and channels between condemned habs. A train rattled past on an elevated rail.

‘Here,’ said Zael, leading her into the ground floor of some kind of community building that had been grossly vandalised. The feral slogans of moody clans were painted on the walls.

‘Here?’ she queried.

‘You saw the sign, right? It said “surgery”.’

‘Uh huh. But it appeared to have been handwritten in blood.’

They entered a broken-down room where a few people sat around on mismatched chairs. An old man, a far-gone, an emaciated addict with the shakes, a worried-looking habwife with a small child, a young drunk with a nasty cut across his brow.

If this is triage, thought Kys, I can’t wait to see the medicae. Some rancid old quack or backstreet abortionist…

Zael led her through an inner door. The Locum was busy. A moody hammer was sitting in an old barber’s chair and, by the light of a makeshift lamp, the Locum was stitching up the twenty centimetre gash across his shoulder. A blade wound, Kys was quite sure.

The room itself was surprisingly tidy, though nothing in it was new. There were a few pieces of medical equipment, tools thrust into a jar of anti-bact gel in a vague nod to sterility.

The Locum had his back to them as he worked. He was of medium build, slim and wiry. His hair was light brown, and he was wearing heavy lace-up boots, black combat baggies, a black vest and surgical gloves.

‘Get in line,’ he called. ‘I’ll get to everyone in turn.’

‘Hey,’ said Zael.

‘Didn’t you hear me?’ the Locum said and turned. Kys saw his face. Strong, calm, rather lined and care-drawn.

His eyes were blue and fiercely intelligent. Right now they were a little puzzled.

‘Zael?’ he said. ‘Zael Efferneti? That you, kid?’

‘Hey, Doctor Belknap.’

‘Throne, Zael. I haven’t seen you for… a year or more. Someone said you were dead.’

‘Not me,’ Zael shook his head.

‘Good. That’s good. Who’s this?’ Belknap asked, looking over at Kys.

‘She’s—’

‘A friend of Zael’s,’ said Patience. ‘I need a medicae. He recommended you.’

‘Yeah? What’s wrong with you?’

‘Nothing. But I need a medicae to come with me and treat two other friends of Zael’s.’

‘You need a medicae,’ said Belknap, ‘go to the local infirmary. Public ward.’

‘I need a certain type of medicae,’ Patience said smoothly.

‘Yeah? What type is that?’

‘The type who sews up a moody hammer’s gangfight wounds, no questions asked.’

Belknap looked back at Zael. ‘Dammit, boy! What have you gotten yourself mixed up in?’

‘Nothing bad, I swear,’ Zael said.

The Locum turned back to his work.

‘Will you come?’ Patience asked.

‘Yes. For Zael’s sake. When I’m finished here.’

THEY WAITED AN hour while he treated the people in line. Then Belknap put on an old, ex-military stormcoat, picked up a black leather practice bag and followed them out onto the sink-street.

‘You not going to lock up?’ Kys asked him.

‘Nothing worth stealing,’ said Belknap. ‘And round here, if you lock a door, folk will kick it in just to know why.’

They caught a sub-train and rattled back across the quarter through the dark, labyrinthine foundations of the hive. Just the three of them, alone in a vandalised carriage.

Kys noticed the old dog-tags on a chain around Belknap’s neck. He didn’t seem more than thirty, thirty-five, although prematurely aged.

‘Guard vet?’ she asked.

‘Company field medic. Six years. I mustered out when the chance came along.’

‘Why?’

‘Couldn’t stand the sight of blood.’

She smiled. ‘And really?’

He looked up at her. His eyes, always half-closed, as if squinting at something bright, they were really something.

‘I don’t even know your name,’ he said. ‘I’m not about to tell you my personal business.’

‘Okay. But between Guard service and sewing up stab-victims in a sink-level ruin, what?’

‘Nine years as a community medicae. I had a practice in the fourth ward of Formal J.’

The carriage rocked violently as the train rode over points in the dark. Kys, who was standing, steadied herself against the handrail.

‘Why’d you stop?’ she asked.

‘I didn’t. I still serve the fourth ward in Formal J.’

‘Yeah, but not officially. You’re a back-street guy.’

‘That’s me. A real vigilante.’

‘So? Why?’

The overheads flickered on and off for a second as the jolting disrupted the live rail. The carriage flashed into strobing blue darkness. Then bare white light again.

‘You ask a lot of questions,’ said Belknap.

‘I’m inquisitive,’ Kys said. ‘Professionally.’

+Leave him alone. Stop asking him stuff.+ Zael sent.

Kys still wasn’t happy about him being able to do that. And when he did it, it hurt a little. He hadn’t refined his talent.

+I’ll ask him what I like, Zael.+ she nudged back.+We’re gonna trust him with Kara and Nayl. I wanna know we can.+

Belknap looked back and forth between them, smiling slightly. ‘What was that?’ he asked, pointing a finger at her then him. ‘You two got a private code or something?’

‘Or something,’ said Zael.

‘What is it? A gang code? Number of blinks? Secret signals?’ Belknap shook his head sadly. ‘Yeah, I’ll lay money it’s a gang code. She’s definitely connected, that one.’

‘Like you wouldn’t believe,’ said Kys.

‘And you,’ Belknap said looking at Zael. ‘I always hoped you’d escape, you know. Not slide in like all the others. I always said that, didn’t I?’

‘You did,’ admitted Zael.

‘I know the odds were stacked against you, especially in a dirt-box like the J. But I hoped. You have a good brain on you, Zael Efferneti. If you’d stuck to scholam, trained maybe, got a decent trade. You could have contributed. Made a life for yourself, against all those odds. But I guess the easy option was always going to suck you in.’

Kys suddenly, oddly, felt rather protective. Zael looked like he was going to cry.

&n

bsp; ‘Zael didn’t take any easy option, doctor,’ she said quietly.

‘Yeah, that’s the real truth, isn’t it?’ the medicae said. ‘The life you people choose, it looks easy. A few risks, a fast fortune. But it’s never easy in the end.’

Kys caught Zael’s eye and they both started laughing.

‘I say something funny?’ Belknap asked.

‘Hysterical,’ said Kys. ‘Now tell me. Why did you quit the community practice?’

Belknap’s compelling blue eyes stared straight up at her. ‘I didn’t. You want to know? Okay. I was disbarred. The Departimento Medicae struck me off and stripped me of my practice. They took away my credentials because I was found guilty of serious malpractice. Okay?’

+Throne, Zael! You brought me to him? We need a medicae, not an incompetent !+

+Ask him why+

+What?+

+Ask the doc why he was struck off.+

‘Why?’ asked Kys.

‘I said. Malpractice. Serious professional misconduct contrary to my oath as a Medicae Imperialis.’

Kys shook her head, reached into her pocket and threw a handful of change at Belknap. ‘Next stop, get off. Find your own way back. I’m sorry to have inconvenienced you. We’ll find someone else. Someone competent.’

Zael got up. ‘Tell her!’ he cried. ‘Tell her the reason, doc!’

Belknap glanced at him. ‘It doesn’t matter, Zael.’

‘Tell her!’

‘It’s my business.’

Zael turned to Kys. ‘They disbarred him for fraud! It was a cash thing! He was only trying to… for Throne’s sake, doc, explain it to her! I don’t know how to describe it!’

Belknap breathed in deeply. ‘My community practice had a budget. It was nothing like enough. You’ve seen the way it is down in the J. I could barely cope. Malnutrition, low-grade pollution disorders, addiction, chronic disease. People were dying – really, actually dying, I mean – because I couldn’t afford the treatments for everyone. So I tried to work the system. I filed false subsist vouchers, claimed for practice expenses that didn’t exist, defrauded the welfare system, just so I could bulk up my budget and afford the things I needed. The things my patients needed. The Administratum caught me, fair and square. Tore up my licence, kicked me out and told me I was lucky not to get a custodial.’

‘See?’ said Zael to Kys.

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

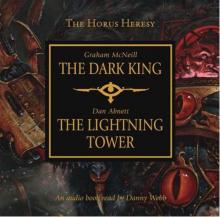

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower