- Home

- Dan Abnett

Prospero Burns Page 26

Prospero Burns Read online

Page 26

He sat by a wall, watching the ceremony take shape. Over time, sitting exactly where he now sat, others had worried away at the wall by the jumping firelight. The ivory panelling lining most of the hold was covered in intricate, hand-done knotwork, the same ancient weave pattern that marked the Rout’s weapons and armour, especially their leatherware. He felt the surface with his fingertips in the shadows, touching where one pattern ended and another took up, blade marks as distinctive as handwriting or voices. He realised how old Nidhoggur was. Two hundred, maybe even two hundred and fifty years old. He thought of the Vlka Fenryka as a well established order, with old and honoured traditions, but this vessel had come out of the fitters’ yards before the Sixth Legion Astartes had even left Terra and been rehoused on bleak Fenris. Hawser had committed most of his life to the search for history, and here it was right under his fingertips. He knew the scale of history, but he’d never really thought about its varying intensities. The long, slow tracts of stability, the abiding Ages of Technology, like endless hot summers, were bland and uneventful compared to the furious two centuries Niddhoggur had witnessed. The remaking of mankind’s fortunes. The rebuilding of mankind’s estate. Would any ship ever last so long or see so much of that which mattered?

Tra assembled. The men came dressed in their pelts and their leatherwork. They were shadows with beast faces, shades with knotwork masks. Hawser could smell the petroleum reek of mjod, mjod in copious quantities. Thralls in horned head-dresses and long, ragged cloaks of patchwork hide moved through the assembling company with drink to fill and refill each lanx. They brought red meat too; panniers of it to stoke the accelerated metabolisms of the Astartes.

Drums were sounding. There was no unifying rhythm. It seemed to be more a matter of pride for a man to be belligerently out of tempo with the neighbouring beats. Playing along with crude pipes and trumpets, made from bone and animal horn, the drums were designed to make noise, a kind of assaulting anti-music. Some of the drums were hoops of wood or bone, or even heated and bent tusk that had been covered in tight skins. Others were giant fish scales, or plates of hammered metal that Hawser eventually realised were pieces of armour taken as trophies from enemies. These hardskin drums made battering rows like cymbals or sistra.

In no order of seniority, and apparently casually, the men came up to the main fires and placed offerings in the ash spill. Hawser saw them leave beads or small trophies, claws and fish teeth, small graven figures shaped from bones and wax, and shell cases etched with knotwork scratches and plumed with seabird feathers. When they left a gift, they took a handful of ash and, removing their leather masks or their entire headgear in some cases, marked their faces with smudges of grey. Najot Threader, his head covered in a tight leather mask that crowned in two vast, winter-black antlers, stood by the fires and watched the men make their marks. He spoke to some, stopping them, a hand on their shoulders, making marks of his own sometimes with ash or red paste on their brows or on their cheekbones under their eyes.

‘What do I give?’ Hawser asked.

Fith Godsmote was sitting beside him, gnawing at a handful of raw meat. Hawser could smell the blood, a pervasive metal stink that was turning his stomach.

‘You’ve got your account to give, so that’s enough,’ Godsmote said. ‘But you should go and get marked by the priest.’

‘I’ve got this feeling,’ said Hawser.

‘What?’ asked Oje from the other side of him.

‘This whole thing is going to end up with me ceremonially offered up in Longfang’s memory.’

‘Hjolda!’ Oje laughed. ‘That’s an idea that would please some!’

‘It’s not how it works,’ said Godsmote, wiping his mouth, ‘but I could have a word with the jarl if you like.’

Hawser scowled at him.

‘You think we blame you for Longfang?’ Godsmote asked.

Hawser nodded.

‘That’s not how it works,’ Godsmote repeated. ‘Wyrd sometimes takes and sometimes gives. Some things seem more important than others when they’re not. Other things, they seem less important than others, when in fact they’re the most important things of all. You didn’t take Longfang from us. It was his time to go. And you’ve brought things to the Rout that they’re grateful for.’

‘Such as?’

Godsmote shrugged.

‘Me,’ he said.

‘You’ve got a pretty high opinion of yourself, Fith of the Ascommani,’ said Hawser.

‘I don’t mean it like that,’ said Godsmote. ‘But I’m useful, a useful arm. I’ve done good work for the jarl and the Rout. I wouldn’t be here unless I was meant to be here. But I wouldn’t be here if you hadn’t fallen out of Uppland that spring.’

‘So I wasn’t such a bad star for you, then?’

‘Neither of us would be here unless we were supposed to be here,’ said Godsmote. ‘You see what I’m saying?’

‘I still feel I’m here on sufferance,’ said Hawser.

‘What does that mean?’ asked Godsmote.

‘I feel I’m tolerated because there’s not a lot else you can do with me.’

‘Oh, there were plenty of things we could have done with you,’ said Oje matter-of-factly as he bit into some meat.

‘Ignore him,’ said Godsmote. ‘Look, they’re closing the bounds so we can begin. Go up now and show us the value of a skjald, and you’ll know you’re not with us under sufferance.’

At the exits and entrances of the hold space, members of Tra were using plasteel hand-axes to strike marks of aversion into the hatch sills and door frames, duplicating the device Hawser had seen Bear make on the graving dock. The area was now contained and access from the outside forbidden until the ceremony was played out. The anti-music noise rose to a peak, and then stopped.

Hawser approached the flames.

Najot Threader, wolf priest, loomed over him like a bull saeneyti, his antlered head backlit by the fire. Despite the crackling blaze and the throat-closing smoke, Hawser felt cold. He pulled the fur that Bitur Bercaw gave him close around his throat and shivered inside his clammy bodyglove. Someone, the priest perhaps, had thrown seedcases and dried leaves on the fire, and they were burning with an unpleasantly sweet aroma.

‘Name yourself,’ said Najot Threader.

‘Ahmad Ibn Rustah, skjald of Tra,’ Hawser replied.

‘And what do you bring to the fireside?’

‘The account of Ulvurul Heoroth, called Longfang, as is my calling,’ said Hawser.

The priest nodded, and marked Hawser’s cheeks with grey paste. Then he leaned forwards with a small straw made from a hollow fish bone. Hawser closed his eyes just in time as Najot Threader used the straw to blow a spray of black paint across his eyes.

His tear ducts stinging, Hawser turned to face the company, circling the main fire as boldly as he felt able. He was trying to control his breathing, trying to remember to pace himself and project his voice. His throat was dry.

With a gesture of confidence and command, he held out a hand. One of the thralls obediently handed him a lanx, and Hawser drank without even checking to see if it was mjod. It wasn’t. The thralls were aware of his biological limits and careful not to cripple him by accident.

Hawser took another sip of watered-down wine, rinsed it around his gums, and handed back the drinking bowl.

‘The first account,’ he said, ‘is the story of Olafer.’

Olafer rose from his place amongst one group and nodded, raising his lanx. There was a ragged cheer.

‘On Prokofief,’ Hawser began, ‘forty great years ago, Olafer and Longfang fought against the greenskins. Bitter winter, dark sea, black islands where the greenskins massed in numbers like the shingle on a beach. A hard fight. Anyone who was there will remember it. On the first day…’

Some parts of the account were greeted with roaring enthusiasm, others with grim silence. Some provoked laughter and others barks of sorrow or regret. Hawser warmed to his task, and began to recognise which of hi

s techniques worked well and which seemed to impress the least.

His only real mis-step came when he described some fallen enemies in one account as ‘finally succumbing to the worms in the soil’.

Someone stopped him. It was Ogvai.

The jarl held up a ring-heavy hand. His look of confusion was accentuated by the heavy piercing in his lower lip.

‘What is that word?’ he asked.

Hawser established that the word ‘worms’ wasn’t known to any of the Wolves. Somehow, he’d slipped out of Juvjk and fallen back on his Low Gothic vocabulary.

It was strange, because he knew the Juvjk word for worms perfectly well.

‘Ah,’ said Ogvai, nodding and sitting back. ‘I understand now. Why didn’t you say so?’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Hawser. ‘I have travelled a long way, and picked up as many words as I have stories.’

‘Continue,’ Ogvai instructed.

He continued. He built in the rests he’d been advised to incorporate, and slept for a few hours at a time as the men drank mjod, and talked. Sometimes, the drumming and the anti-music would start up again, and some of the men would dance a sort of furious anti-dance, a wild, heedless, ecstatic frenzy that looked as if they had been possessed or suffered a mass psychogenic chorea. It grew so warm in the chamber that Hawser began to go to the fireside without his pelt when he was called.

It was a test of endurance. He ate what the thralls brought him, and drank copiously to maintain his fluid levels. The stories, even the shortest and most incomplete tales, seemed to crawl by, etching out Longfang’s lifespan slowly, like careful knotwork. Four hundred and thirty-two stories took time to tell properly.

The last of all would be the account of Longfang’s death, a tale that combined Hawser’s memories with those of Jormungndr Two-blade. Hawser knew he would be tired by the time he reached it.

He also knew he had to make it the best of all.

It was still a long way off, with over sixty stories left to tell, when Ogvai rose to his feet. They had stopped to rest. Aeska shook Hawser awake. The drumming was quietening down from another frenzied bout, and dancers were slumping to the deck, laughing and reaching out for mjod.

‘What’s happening?’ Hawser asked.

‘Part of the sending off is the choosing of the next,’ said Aeska.

There were several men in Tra who were alleged to have the sight like Longfang. They also served in priest-like capacities, and one would be selected to fulfil Longfang’s senior role.

They came forwards and knelt in a circle around Ogvai. The jarl’s centre-parted hair fell straight on either side of his face like black-water cataracts. He was stripped to the waist. He tilted his head back and reached out his hands, flexing the huge muscles of his arms, his shoulders and his neck. Grey ash had been smeared on his snow-white flesh. Like Hawser, Ogvai had black paint across his eyes.

In his right hand, he held a ceremonial blade. An athame.

The jarl started to speak, intoning in turn the virtues of each candidate.

Hawser wasn’t listening. The athame, the pose with the arms outstretched, it violently reminded him of the figure in the Lutetian Bibliotech, a story that had been locked in his head for decades, a story he had only brought out again for Heoroth Longfang.

He stared at the athame.

It wasn’t just similar. Kasper Hawser was an expert in these things. He knew about types and styles. This wasn’t a misidentification based on similarity.

It was precisely the same blade.

He rose to his feet.

‘What are you doing?’ asked Godsmote.

‘Sit down, skjald,’ said Oje. ‘It’s not your turn.’

‘How is that the same?’ asked Hawser, staring at the ceremony.

‘How is what the same?’ asked Aeska, annoyed.

‘Sit down and shut up,’ growled another Wolf.

‘How is that blade the same?’ Hawser asked, pointing.

‘Sit down,’ said Godsmote. ‘Hjolda! I’ll smite you myself if you don’t sit down!’

Ogvai had made his choice. The other candidates bowed their faces down to the deck to acknowledge the authority of the decision. The chosen man rose to his feet to face the jarl.

Tra’s new rune priest was young, one of the younger candidates. Aun Helwintr had earned his name because his long hair was as white as deep season snow, despite his age. The leatherwork of his mask was so dark it was almost black, and he wore the pelt of a tawny animal. He was known for his strange, distant manner, his odd bearing, and his habit of getting into impetuous fights that he miraculously survived. Wyrd gathered inside Aun Helwintr in a way that Ogvai wanted to harness.

Some rite was about to take place. Hawser felt the silence close in. He believed himself to be the cause of it.

That was not the case. The Wolves had turned to look towards one of the chamber hatches, golden eyes baleful in the firelight.

A group of thralls stood there, escorting a terrified-looking member of Niddhoggur’s bridge crew. They had entered despite the marks of aversion at the doorways.

Ogvai Ogvai Helmschrot swapped the athame into his left hand and picked up his war axe. He strode across the hold space to dismember them for their violation.

Halfway across the deck, he stopped and checked himself. Only an idiot would ignore a mark and break in on such a private ceremony.

Only an idiot, or a man with a message so important that it couldn’t wait.

‘So you liked the account?’ Hawser asked. ‘It amused you? It distracted you?’

‘It was amusing enough,’ said Longfang. ‘It wasn’t your best.’

‘I can assure you it was,’ said Hawser.

Longfang shook his head. Droplets of blood flecked from his beard.

‘No, you’ll learn better ones,’ he said. ‘Far better ones. And even now, it’s not the best you know.’

‘It’s the most unnerving thing that happened to me in my old life,’ said Hawser with some defiance. ‘It has the most… maleficarum.’

‘You know that’s not true,’ said Longfang. ‘In your heart, you know better. You’re denying yourself.’

Hawser woke with a start. For a terrible, rushing moment, he thought he was back in the Bibliotech, or out on the ice fields with Longfang, or even in the burning courtyard of the Quietude’s sundered city.

But it was all a dream. He lay back, calming down, trying to slow his panicked breathing, his bolting heart. Just a dream. Just a dream.

Hawser settled back onto his bed. He felt tired and unrefreshed, as if his sleep had been sour, or sedative assisted. His limbs ached. Sustained artificial gravity always did that to him.

Golden light was knifing into his chamber around the window shutter, gilding everything, giving the room a soft, burnished feel.

There was an electronic chime.

‘Yes?’ he said.

‘Ser Hawser? It is your hour five alarm,’ said a softly modulated servitor voice.

‘Thank you,’ said Hawser. He sat up. He was so stiff, so worn out. He hadn’t felt this bad for a long time. His leg was sore. Maybe there were painkillers in the drawer.

He limped to the window, and pressed the stud to open the shutter. It rose into its frame recess with a low hum, allowing golden light to flood in. He looked out. It was a hell of a view.

The sun, source of the ethereal radiance, was just coming up over the hemisphere below him. He was looking straight down on Terra in all its magnificence. He could see the night side and the constellation pattern of hive lights in the darkness behind the chasing terminator, he could see the sunlit blue of oceans and the whipped-cream swirl of clouds, and, below, he could see the glittering light points of the superorbital plate Rodinia gliding majestically under the one he was aboard, which was…

Lemurya. Yes, that was it. Lemurya. A luxury suite on the underside of the Lemuryan plate.

His eyes refocussed. He saw his own sunlit reflection in the thick glass of the wi

ndow port. Old! So old! So old! How old was he? Eighty? Eighty years standard? He recoiled. This was wrong. On Fenris, they’d remade him, they’d—

Except he hadn’t been to Fenris yet. He hadn’t even left Terra.

Bathed in golden sunlight, he stared at his aghast reflection. He saw the face of the other figure reflected in the glass, the figure standing just behind him.

Terror constricted him.

‘How can you be here?’ he asked.

And woke.

The chamber was cold and dark, and he was on the deck under his pelt. He could feel the distant grumble of Nidhoggur’s drive. Nightmare sweat was cold on his gooseflesh.

No one had seen Ogvai since the interruption to the ceremony. Fith said that Tra had received an urgent notification and been retasked, but there was nothing concrete. As usual, Hawser didn’t expect to be told much. He waited a while to see if the ceremony would be resumed, but it was clear the moment had passed. The fires were allowed to go out, and the men of Tra dispersed. Hawser found most of them in the arming chambers, readying their weapons and their battlegear, or in the practice cages. Blades were being whetted so they held the best edge, armour was being polished and adjusted. Small refinements were being added, small trinkets or decorations. Beads and loops of teeth were being wired in place. Marks of aversion were being notched onto the tips of bolter rounds. In the harder gantry lighting of the arming chambers, Hawser reflected how much like flayed humans the Wolves looked in their leatherwork gear. The knotwork and straked pieces resembled sinews, tendons and sheets of muscle.

No one paid him any heed. His head bubbling with unhappy dreams and a sense that he had slept too long for his own good, he wandered back to the hold space.

The air smelled of cold smoke. He touched the marks of aversion on the door sills, felt the rough metal edges where they, like the others marked in place before them, had been defaced and robbed of potency.

Hawser wandered into the hold space, and stood for a while beside the smouldering heap of the main fire. He saw the glitter of the offerings the men had left in the grey ashes, and the stains of mjod splashed on the decking. He saw the discarded drums and sistra. Thralls had collected up all the lanx dishes and flasks. There were no signs of the ritual items used by either Najot Threader, the wolf priest, or Ogvai.

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

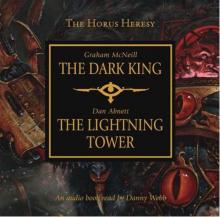

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower