- Home

- Dan Abnett

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Page 26

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Read online

Page 26

The Lith's surface became discoloured, as if mottled by mould. It shuddered, cracking the obsidian around it.

Then its inner luminescence sputtered and went out, and it became indistinguishable from the black volcanic glass that surrounded it.

When the Lith died, so did its servants, and so did the blasphemy. Checking that Medea was now just sleeping soundly, I nursed the damaged pod back down the cavern in time to see the last stringy remnants of the foul worm combusting and sliding off the translithopede's buckled hull. The air was thick with dirty cinders and the smoke of burning fat.

The burning corpses of cultists littered the chamber floor. Motionless stalkers stood in their midst, cycling on pause, waiting for the next command.

Broken and twisted, the great burrower was at least intact. When I brought the pod into the dock-bay, Bure's own tech-adepts themselves emerged to take care of Medea's unconscious body.

The companionway floor was raked over at an angle. Bure's engineer priests were still trying to repair the inertial dampers.

Acrid smoke filled the air, unpleasantly scented by the fat-fires outside. Aemos met me in the doorway of the control chamber and hugged me briefly in a rare display of affection. Bure had shed his orange robe. A sinister, stark, inhuman silhouette, he watched our very human exchange from the edge of the podium, backlit by fires raging in the workstations below.

'We're fine now, old friend,' I said to Aemos.

He broke the embrace, as if guilty. 'You did well, Gregor. Marvellously! I... I didn't mean any disrespect...'

It was at times like that I wished I could still smile. I am too used to my face being the impassive mask Gorgone Locke gave me.

Using my will gently, so he might understand the truth of my words, I said, 'No disrespect taken, old friend.'

Aemos smiled sheepishly and turned away.

His suspensors hissing, Bure glided over to me. To my surprise, he hugged me too. It was brief and clumsy, his servo arms conveying no warmth. I felt terrible sorrow for him then. His human core had been moved by the events and he had seen and copied Aemos's impromptu display of affection. Just then, I believe, he passionately wanted to be human again. Just for a moment. But his vicing arms had no more emotion in them than the tight handshake with which he had first greeted me.

He swung away, his arms to his sides. His green eye-lights flicked back and forth over the repair teams as they worked to contain the damage.

'I have never said/ he began, his voxed voice toneless and cold, though it tried to be neither of those things. 'Hapshant. He thought the world of you, Eisenhorn. He told me once that he believed you would eclipse his career with your own. I think he was right.'

'Thank you, magos.'

He turned around to look at me. His eye were tiny spots of emerald fire.

'You never did say what brought you here.'

'Recent matters somewhat overtook us, magos.'

Yes. But still, you never did say...'

'I have to explain the... circumstances that have changed in my life, magos. I will explain them carefully, in the hope that you will understand and not think badly of me. But first... I gave you something to safeguard and study, a century ago. I'd like to see it again.'

It was ironic, as if some karmic balance was at work. Of course, I didn't believe in such things. Bure had burrowed and tunnelled his way fruitlessly through the heart of Cinchare for eleven weeks, only to have Aemos casually present him with the Lith's location. And we had gone deep into the mines to find Bure only to learn that what I had come to Cinchare for had been safely locked away in the annex of the Adeptus Mechanicus all along, had I but looked for it.

It took thirty hours for the ailing translithopede to make its way back to the surface. Once we'd broken through the blue gypnate crust at the Imperial Allied mineworks, I sent Aemos and Medea back to the cutter to check in with Bequin and the others, still waiting aboard the Essene at high orbit. I hoped they hadn't done anything foolish in my absence.

Bure took me to the annex. His encoded touch brought the sanctum to life, and lit long hallways to either side of the Mechanicus chapel. He led me down one of these, the illumination plates still flickering as they warmed up after such a prolonged period of disuse.

The magos linked his thoracic neural cables to a wall socket and disengaged a lock. A heavy, armoured door slid open. Then another, inside the first, then a third, a sturdy iris valve that withdrew segmentally into the wall frame with a noise like swords sheathing.

This is what you want,' said Bure. 'He has been most informative, over the years/

'I'll review your reports later, magos/ I said. 'Leave me with him now/

Bure withdrew.

I stepped through the iris valve and down three grilled steps into the cell, feeling the nauseating static prickle of the psychic dampening fields. Every surface was dusted with ice-crystals. There was a crackle of synaptic energy.

'Hello, Eisenhorn/ said a hollow, vox-projected voice. It came from a casket that squatted on a basalt block in the centre of the room. Both casket and stone were caked in ice. Tiny lights darted and blinked inside the casket's open lid.

I prepared myself. Then I replied.

'Pontius Glaw. We meet again/

TWENTY

Interview with the Damned.

Bure, warsmith.

Orbul Infanta.

'Let me make sure I understand you, Eisenhorn/ said the disembodied voice of Pontius Glaw, slowly and contemptuously. 'You think I'm going to help you?'

I cleared my throat. 'Yes.'

Pontius laughed. Synapse leads connected to the gold circuits of his engram sphere flashed in series. 'I didn't think a man of such studied dullness and sobriety as you would have the ability to surprise me, Eisenhorn. My mistake.'

'You will help me/ I said, quietly but emphatically.

I brushed frost from the grilled steps and sat down facing his casket. It was claw-footed, rectangular, compact and filled with complex technology designed for one purpose: the support and operation of the engram sphere, a rough-cut nugget the size of a clenched fist in which resided the intellect - and perhaps the soul - of one of the most notorious heretics in the Imperium.

Pontius Glaw, dead in body for nigh on three hundred years, had been in his physical life one of the more unwholesome products of the powerful Glaw dynasty. That family line, part of the high nobility of Gudrun, had whelped many heretics in its time, the last of whom had been instrumental in the affair of the Necroteuch. Supported by the considerable efforts of Imperial Navy Security, I had all but crushed their poisonous lineage, and in the process had captured the engram sphere of Pontius Glaw.

His family and their minions had attempted to sacrifice thousands of innocents in order to restore him to physicality. That, too, I had denied.

Once the affair had ended, I had been left with this casket full of heretical spite. In terms of technology alone, it was a wonder, and there was no telling what secrets the Pontius might have in it. So instead of destroying it, I had passed it into the safekeeping of Magos Geard Bure. Bure, I knew, would have the time and skill enough to unlock its technical marvels at least. And he was trustworthy.

But from time to time in that past hundred years, I had questioned the validity of that decision. In all honesty, I should have surrendered the Pontius to the Ordo Hereticus for examination and disposal. The fact that I hadn't sometimes played on my conscience, for it suggested deceit and unwholesome subterfuge on my part. In the light of events in the past year, I found myself fighting back the notion that perhaps my accusers were right. Had it been the act of an unsound man to secret away such a radical entity?

Aemos had consoled my spirits, reminding me that the casket utilised mind-impulse technology undoubtedly stolen from the Cult Mechanicus. There was, he said, no question that such a device should be in the custody of the Adeptus priesthood.

'Go on then/ Pontius said. 'Make your case. Why would I help you?'

'

I require specialist information that I'm certain you have. Certain lore/

You are an inquisitor, Eisenhorn. All the resources of the Imperium are at your disposal. Am I to understand that, well, that your scope has become somewhat limited?'

I was damned if I was going to tell this monster of the straits I was in. And even though he was right in a way, there was no Imperial archive I knew of that could answer my questions.

'What I need might be regarded as... proscribed knowledge/

Ahhhhh...'

'What? "Ah" what?'

Even without features or body language to read, Pontius seemed insufferably pleased with himself. 'So you've finally reached that place. How wonderful/

What place?' I felt uncomfortable. I had been planning this interview for months, and now control was slipping entirely to Glaw.

The place where you cross the line/

'I hav-'

'All inquisitors cross the line eventually/

'I tell y-'

All of them. It's an occupational hazard/

'Listen to me, you worthless-'

'Methinks Inquisitor Eisenhorn protests too much. The line, Gregor. The line! The line between order and chaos, between right and wrong, between mankind and man-unkind. I know it, because I've crossed it. Willingly, of course. Gladly. Skipping and dancing and delighting. For the likes of you, it is a more painful process/

I rose. 'I don't think this conversation is going anywhere, Glaw. I'm leaving.'

'So soon?'

'Perhaps I'll be back in another century or two.'

'It was on Quenthus Eight, in the spring of 019.M41.'

I paused at the cell hatchway. 'What was?'

'The moment I crossed the line. Would you like to hear about it?'

I was rattled, but I returned to my seat on the steps. I knew what he was doing. Imprisoned in his casket without touch or smell or taste, without any sensory stimulation, Pontius Glaw craved company and conversation. I had learned that much during my long interrogations of him aboard the Essene ten decades before during the voyage to the remote system KCX-1288. Now he was simply feeding me morsels to make me stay and talk to him.

However, in a hundred years of captivity he had never come close to revealing such intimate details of his personal history.

'019.M41. A busy year. The buttress worlds of the far eastern rim were resisting a Holy Waaagh by the greenskins, and two of the High Lords of Terra had been assassinated in as many months by disaffected Imperial families. There was talk of civil war. The sub-sector's trader markets had crashed. Trade was bad. What a year. Saint Drache was martyred on Korynth. Billions starved in the Beznos famine.'

'I have access to history texts, Pontius,' I said dryly

'I was on Quenthus VIII, buying fighters for my pit-games. They're a good breed, the Quenthi, long in the hams and quite belligerent. I was, perhaps, twenty-five. I forget exactly. I was in my prime, beautiful.'

There was a long silence while he considered this reflection. Light-sparks pulsed along his wires.

'One of the pit-marshals at the amphitheatre I was visiting advised me to see a fighter who had been bought in from the very edges of the Ultima Seg-mentum. A great, tanned fellow from a feral world called Borea. His name was Aaa, which meant, in his tongue, "sword-cuts-meat-for-women-prizes". Isn't that lovely? If I had ever sired a son, a human one, I mean, I would have called him Aaa. Aaa Glaw. Quite a ring to it, eh?'

'I'm still on the verge of leaving, Glaw.'

The voice from the casket chuckled. This Aaa was a piece of work. His teeth were filed into points and his fingertips had been bound and treated with traditional unguents since his birth so that they had grown into claws. Claws, Eisenhorn! Fused, calcified hooks of keratin and callouses. I once saw him rip through chainmail with them. Anyway, he was a true find. They kept him shackled permanently. The pit-marshal told me that he'd torn a fellow prisoner's arm off during transit, and scalped a careless stadium guard. With his teeth.'

'Charming.'

'I bought him, of course. I think he liked me. He had no real language, naturally, and his table manners! He slept in his own soil and rutted like a canine.'

'No wonder he liked you.'

The frost crackled around the casket. 'Cruel boy. I am a cultured man. Ha. I was a cultured man. Now I am an erudite and dangerous box. But don't forget my learning and upbringing, Eisenhorn. You'd be amazed how easy it is for a well-raised and schooled son of the Imperium to slide across that line I mentioned.'

'Go on. I'm sure you had a point to make.'

Aaa served me well. I won several fortunes on his pit-fights. I won't pretend we ever became friends... one doesn't become friends with a favourite carnodon now, does one? And one certainly never makes friends with a commodity. But we built an understanding over the years. I would visit him in his cell, unguarded, and he never touched me. He would halt out old myths of his home world, Borea. Vicious tales of barbary and murder. But I'm getting ahead of myself. The moment, the moment was there on Quenthus, in the amphitheatre, under the spring sun. The pit-marshal showed me Aaa, and tempted me to purchase him. Aaa looked at me, and I think he saw a kindred soul... which is probably why we bonded once he was mine. In his simple, broken speech, he implored me to buy him, telling me graphically what sport I would have of him. And to seal the deal, he offered me his tore'

'His tore?'

'That's right. The slaves were allowed to keep certain familiar items provided they weren't potential weapons. Aaa wore a golden tore around his neck, the mark of his tribe. It was the most valuable thing he possessed. Actually, it was the only thing he possessed. But no matter... he offered it to me in return for me becoming his master. I took it, and, as I said, I bought him.'

'And that was the line?' I sat back, unimpressed.

4Vait, wait... later, later that same day, I examined the tore. It was inlaid with astonishing technology. Borea might have been a beast-world by then, but millennia back, it had clearly been an advanced outpost of mankind. It had fallen into a feral dark age because Chaos had touched it, and that tore was a relic of the decline. Its forbidden, forgotten technology focussed the stuff of the Darkness into the wearer's mind. No wonder Borea, where every adult male wore one, was a savage waste. I was intrigued. I put the tore on.'

'You put it on?'

'I was young and reckless, what can I say? I put it on. Within a few hours, the tendrils of the warp had suffused my receptive mind. And do you know what?'

'What?'

'It was wonderful! Liberating! I was alive to the real universe at last! I had crossed the line, and it was bliss. Suddenly I saw everything as it actually was, not as the Ministorum and the rot-hearted Emperor wanted to see it. Engulfing eternity! The fragility of the human race! The glories of the warp! The fleeting treasure of flesh! The incomparable sweetness of death! All of it!'

'And you ceased to be Pontius Glaw, the seventh son of a respectable Imperial House, and became Pontius Glaw, the sadistic idolator and abomination?'

A boy's got to have a hobby'

Thank you for sharing this with me, Pontius. It has been revealing.'

'I'm just getting started.

'Goodbye.'

'Eisenhorn! Eisenhorn, wait! Please! I-'

The cell hatches clanged shut after me.

I waited two days before I returned to see him. He was sullen and moody this time.

I entered the cell and set down the tray I was carrying.

'Don't expect me to talk to you/ he said.

'Why?'

'I opened my soul to you the other day and you... walked out/

'I'm back now/

'Yes, you are. Closer to that line yet?'

You tell me/ I leaned over and poured myself a large glass of amasec from the decanter on the tray. I rocked the glass a few times and then took a deep sip.

'Amasec/

'Yes/

Vintage?'

'Fifty year old Gathalamor vintage, aged in burwoo

d barrels/

'Is it... good?'

'No/

'No?'

'It is perfect/

The casket sighed.

'You were saying. About that line?' I asked.

'I... I was saying I was most annoyed with you/ Pontius returned, stubbornly.

'Oh/ I casually slid a lho-stick from the paste-board tub I had backhanded from Tasaera Ungish's stateroom. I lit it and took a deep drag, exhaling the smoke towards the infernal casket. Nayl had injected me with powerful anti-intoxicants and counter-opiate drugs just half an hour earlier, but I sat back and openly seemed to relish the smoke.

'Is that a lho-stick?'

Yes, Pontius/

'Hmmm...'

'You were saying?'

'Is it good?'

You were saying?'

'I... I've told you of my slip. My crossing of the line. What else do you want of me?'

The rest. You think I've crossed the line too, don't you?'

Yes. It's in your bearing. You seem like a man who has understood the wider significance of the warp/

'Why is that?'

'I told you it happens to all inquisitors sooner or later. I can imagine you as a young man, stiff and puritanical, in the scholam. It must have seemed so simple to you back then. The light and the dark/

'Not so obvious these days/

'Of course not. Because the warp is in everything. It is there even in the most ordered things you do. Life would be brittle and flavourless without it/

'Like your life is now?' I suggested, and took another sip.

'Damn you!'

'According to you, I'm already damned/

'Everyone is damned. Mankind is damned. The whole human species. Chaos and death are the only real truths of reality. To believe otherwise is ignorance. And the Inquisition... so proud and dutiful and full of its own importance, so certain that it is fighting against Chaos... is the most ignorant thing of all. Your daily work brings you closer and closer to the warp, increases your understanding of orderless powers. Gradually, without noticing it, even the most puritanical and rod-stiff inquisitor becomes seduced/

'I don't agree/

Pontius's mood seemed to have brightened now we were engaged in debate again. The first step is the knowledge. An inquisitor must understand the basic traits of Chaos in order to fight it. In a few years, he knows more about the warp than most untutored cultists. Then the second step: the moment he breaks the rales and allows some aspect of Chaos to survive or remain so that he can study it and learn from it. I wouldn't even bother trying to deny that one, Eisenhorn. I'm right here, aren't I?'

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

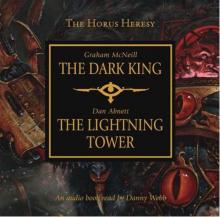

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower