- Home

- Dan Abnett

THE WARMASTER Page 23

THE WARMASTER Read online

Page 23

‘I’ll go see Curth,’ he said.

‘I think you’d better. Let me come with you.’

Kolea shook his head. His vision was still swimming.

‘No, it’s all right.’

Concerned, Daur stood and watched as Gol shuffled away. He watched as Gol turned and took a long look at Yoncy, playing in the yard.

‘What’s this now?’ asked Didi Gendler, flicking aside a lho-stick.

A large, gloss black transport was pulling into the yard, followed by two staff vehicles. They were gloss black too, gleaming in the watery sunlight. The vehicles edged around the bottleneck of the munition trucks and the men unloading them, and drew up beside the medicae trailer.

‘They’re burying her, Didi,’ said Meryn.

‘Gaunt’s bitch?’ asked Jakub Wilder.

Meryn nodded. The three of them were standing at the side of the yard, under one of the plastek awnings.

‘She gets a fething funeral?’ asked Gendler.

‘Yeah,’ said Meryn.

‘A private funeral?’ asked Wilder.

‘Of course,’ said Meryn. ‘She was… what do you call it? High-hive.’

‘She was a gakking lifeward,’ snarled Gendler. ‘Some low-born tart. No House blood in her.’

‘No blood in her at all, now,’ said Meryn.

‘That’s fething cold,’ said Wilder.

‘She worked for the aristo scumbags, though, didn’t she?’ said Meryn. ‘Employed by House Chass. All that fancy kit and augmetics. So she gets the works.’

‘She gets the works because she’s Gaunt’s bitch,’ said Gendler.

‘She gets the works because she was lifeward to Gaunt’s brat, and Gaunt’s brat is high-hive blood, so that’s the way it goes,’ said Meryn.

He could see that Gendler was seething. Didi Gendler had been high-hive once, but he’d lost it all in the Zoican War, and Guard service during the act of Consolation had been about his only option. Sometimes, he got so wound up at his loss of status, Meryn thought the man would split right out of his pale, fair-haired skin and his raw bones would go stomping off to strangle someone. Gendler’s resentment for Felyx Chass was legendary. He hated the privilege that got Felyx his sinecure in the regiment, and his special treatment.

‘If I died,’ Gendler said, ‘Gaunt wouldn’t even drag his heel in the dirt to make a grave.’

Meryn nodded.

‘I have a question,’ said Wilder. ‘Fancy private funerals like that? They cost a lot. A fething lot. So who’s paying for it?’

‘Histye, soule,’ said Ezra.

Gaunt looked up from his work. The Nihtgane was staring out of the window into the yard below. Gaunt got up. His desk was covered in data-slates. True to his word, Biota had couriered full technical specs for the Urdesh theatre over to Gaunt. There was a lot to go through, and what he’d studied already had left him worried.

Besides, he was distracted. The shade of Maddalena stood over him. He felt a numb sense of loss. Part of him worried that the loss would grow sharper as he processed it. Another part was afraid that his life had simply made him unfeeling towards death, that his capacity for emotional connection had withered to nothing.

Whatever, he’d lost track of time. It was almost noon.

He went over to the window and saw what Ezra was looking at.

The cortege had arrived. The hired mourners, in their long black coats, had got out and were walking towards the medicae trailer.

‘Can you go find Felyx and tell him we’ll be setting off shortly?’ he asked Ezra.

The Nihtgane nodded.

‘Ezra?’

‘Soule?’

‘I’ve asked Dalin to keep an eye on Felyx, now Maddalena’s gone. But as a favour to me, could you…’

Ezra cocked his head quizzically.

‘Just watch over him,’ said Gaunt. ‘Nothing intrusive, just from the shadows. But watch him, and look after him, and if things get dangerous, step in and help Dalin.’

‘You need not ask it,’ said Ezra.

Ezra passed Blenner as he left the room.

‘Got a moment, Ibram?’ Blenner asked lightly.

Gaunt was putting on his black armband.

‘No, Vaynom.’

‘Oh, is it that time already?’

Blenner went to the window. He watched as the mourners brought the coffin out and slid it into the back of the transport. Curth, arms folded, supervised them.

‘Well, it can wait,’ said Blenner. ‘Later on.’

‘I’m at staff later on,’ said Gaunt.

‘This evening, then?’

‘All day, Blenner. I’ve been called in for a round of more detailed debriefs, then there’s all that to work through.’

Gaunt nodded towards the data-slates on his desk.

‘I’m sure staff knows all about the war, Ibram,’ said Blenner.

Gaunt looked at him.

‘I’m not sure they do,’ he said. ‘I’ve been looking at that material. I think I’ve seen something they’ve missed.’

‘You’ve seen something they’ve missed?’ said Blenner with a smile. ‘Something that all the lords militant and fancy-pants generals and chief tacticians and intelligence service officers have–’

‘Yes,’ said Gaunt. ‘Because they’re too close. I’m fresh eyes. And it’s startlingly obvious to me.’

Blenner swallowed. He felt his stress rising, his palms beginning to sweat. He knew that look. When Ibram Gaunt got that look, you knew shit was coming. Blenner did not want shit to be coming.

He crossed to the side table and helped himself to a glass of amasec.

‘I presume you’re not going to share your special theory with me?’ he asked. As he poured the drink, he used his body to shield the fact he was slipping a pill from his pocket. Feth! Almost the last one.

‘I’m not sharing it with anybody except staff just yet,’ said Gaunt.

Blenner palmed the pill and knocked it down with the amasec.

‘Throne, but elevation has changed you,’ he said, trying to sound light. Gaunt didn’t rise to it.

‘Have you spoken to Ana?’ Blenner asked.

‘No. Why?’

‘Not at all?’ asked Blenner.

‘In the course of regular duties, yes, but not otherwise. Why?’

‘I think you should,’ said Blenner, regretting that he’d knocked the amasec back in one and wondering if he could get away with a top up.

‘Why?’ asked Gaunt, staring at him.

‘Well, things have been so hectic, Ibram. So much has happened. And now that poor lady is dead, and you and Ana were such good friends–’

‘Did she say something to you?’

‘Ana? No! No, I just think… you know… You must be aware that Doctor Curth is very fond of you…’

Gaunt picked up his cap.

‘I don’t have time for this, Vaynom, and even if I did, it isn’t appropriate.’

‘A man talking to his best and oldest friend isn’t appropriate?’ asked Blenner, helping himself to another amasec anyway.

‘Feth’s sake, Blenner. What do you want?’

Blenner looked wounded.

‘Well, if you’re going to be like that, lord militant commander,’ he said. ‘I think you and Curth should talk. She’s troubled.’

‘I understood,’ said Gaunt, ‘that you were keeping good company with Doctor Curth. A fact you’ve clumsily dropped into conversation on several occasions.’

‘I am. I have. We have an understanding.’

‘What have you done, Vaynom?’

‘Nothing.’

Gaunt took a step forwards.

‘Have you messed with her?’ he asked.

‘What?’

‘I know you, Blenner. Remember that. You’re a rogue. A lush. A ladies’ man. You get what you’re after and then you leave without a goodbye. You don’t care about people.’

‘Now hang on–’

‘If you’ve strung her along,�

� said Gaunt. ‘If you’ve messed with her affections and then done your usual trick of bolting. If you’ve hurt her–’

‘That’s rich, coming from you!’ snapped Blenner.

‘Lose the tone! What did you do to her? What have you said?’

‘It’s not like that at all!’ replied Blenner. His hands were shaking. ‘We’re not together or anything. We’re friends. Feth you, Ibram! You’re the one she has feelings for. You always have been. Take a long look at yourself. A long, hard look! Because if anyone is messing Ana Curth about, it’s you! She cares! She’s worried about you! She’s worried that your grief might–’

‘That’s enough, commissar,’ said Gaunt.

‘Yes, well.’

‘I’ve known you a long time, Blenner. I’ve put up with your antics and your flaws for a long time. You can talk to me with a familiarity that very few other people in this regiment can get away with. But when you’re in uniform, you don’t address me like that.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Blenner. He put the glass down.

‘That charm of yours only runs so far,’ said Gaunt. ‘Sort yourself out, and fast, or I’ll have to review your posting with this regiment.’

‘Yes, sir.’

There was a knock at the door. One of the Tempestus Scions looked in.

‘I’m coming, Sancto,’ said Gaunt.

‘My lord,’ said the Scion, ‘word has just arrived. You are summoned to the palace.’

‘No, I’m due this afternoon.’

‘The summons was very clear, my lord. You are to report immediately.’

‘But I’ve got a funeral to–’

Gaunt stopped. He took a deep breath.

‘Bring the transport round, Sancto,’ he said. ‘I’ll be right there.’

Blenner looked at Gaunt.

‘That’s bad timing,’ said Blenner. ‘I know you would want to go with your son. Do you want me to–’

‘No, Vaynom. I don’t want you to do anything.’

Gaunt buckled on his sword, straightened his coat, and left the room.

Alone, Blenner stared at the glass on the side. His hands were shaking badly and his heart was racing. He saw his future sliding away from him. Gaunt’s intimation that bad trouble was coming was bleak enough. He didn’t want that. But he had comforted himself that now he was posted to the command group of a militant commander, privilege would protect him. That kind of swing could get a man out of the front line.

But if Gaunt was tiring of him, if he’d pushed the friendship too far, then he’d get a posting. He’d get rotated out. He’d get a placement with some feth-knows regiment, and he’d probably end up smack on the line.

At the fething shitty end of the fething war.

Blenner killed the drink in one. He needed to be calm. He needed pills. He needed to call in a favour with Wilder.

Hark walked in.

‘The cortege is here,’ said Hark. ‘Where’s Gaunt?’

‘I haven’t seen him,’ said Blenner.

‘What’s up with you, Vaynom?’

‘Nothing,’ said Blenner. He forced a smile. ‘Nothing at all, Viktor.’

He walked out and left Hark staring, baffled.

‘Don’t get up,’ said Gaunt. Criid did anyway.

‘What’s the matter, sir?’ she asked. Gaunt stepped into her room and pulled the door closed.

‘I’ve been called to staff. I have to go.’

‘I’m sorry,’ she said.

‘I wondered if you could–’

‘Of course,’ Criid said. ‘I was going anyway.’

Gaunt took off his armband and handed it to her.

‘And, Tona, I hoped you might explain–’

‘I will, sir,’ she said.

‘Express my apologies. Try to make Felyx understand.’

‘I will, sir,’ she said.

‘Thank you, captain.’

A crowd had gathered in the yard. Some had just come to look at the cortege out of curiosity. Others had come to stand in respect.

Felyx walked into the yard and approached the gloss black vehicles. He was wearing his number one uniform. He looked very drawn and solemn.

‘Where is… the militant commander?’ he asked.

Curth shook her head.

‘I’m sure he’s coming, Felyx,’ she said.

‘He’s late. I sent Dalin to find him,’ said Felyx.

Zwiel came over to stand with them. The three of them stared at their reflections in the smoked glass of the transport’s rear windows.

‘Saint Kiodrus Emancid is a good templum,’ said Zwiel. ‘A fine place. Very tall. I hear the ecclesiarch is a splendid fellow too. Not stupid, which is a benefit at times like this.’

He held out a small posey of flowers to Felyx.

‘Just a simple garland I made,’ he said. ‘For you to take. Islumbine.’

‘Where did you find islumbine?’ asked Curth, surprised.

‘I found it growing by the Sabbatine altar in the chapel near here,’ said Zwiel. ‘Nowhere else. It seemed like a blessing to me.’

He looked at Felyx.

‘They’re the holy flower, sacred to Saint Sabbat.’

‘I know what they are,’ said Felyx. He took the flowers.

Criid joined them. She looked tall and very commanding in her formal uniform. The black band was around her arm.

‘We’re waiting for Gaunt,’ Curth told her.

‘Dalin’s gone to fetch him,’ said Felyx.

‘Felyx,’ said Criid. ‘The militant commander has been called to the palace. A priority summons from staff. He sends his sincere apologies.’

‘Oh, that’s fething unbelievable,’ whispered Curth.

‘My father’s not coming?’ asked Felyx.

‘He is very sorry,’ said Criid. ‘He’s asked me to attend on his behalf, as captain of A Company, to represent the regiment.’

‘He can’t be bothered to come?’ Felyx asked.

‘It’s not like that,’ said Criid.

‘He can’t be bothered to come,’ said Felyx. ‘Fine. I don’t care. He can go to hell.’

‘Aw, look at that,’ whispered Meryn at the back of the crowd.

‘The little fether’s tearing up,’ said Gendler with far too much satisfaction in his voice. ‘Boo hoo! Where’s your high-and-mighty daddy now, you little brat?’

‘Typical,’ said Wilder. ‘Gaunt doesn’t care about anybody. Not even his own son.’

‘It’s tragic, is what it is,’ agreed Meryn.

‘I still want to know who’s paying for all this crap,’ muttered Wilder.

‘That would be Felyx Chass,’ said Blenner, appearing behind them. They straightened up fast.

‘As you were,’ said Blenner. ‘I was actually looking for you, Captain Wilder. Just checking in while I remembered. I wondered if… if any of your recent inspections had turned up any more contraband? Any pills, you know?’

Wilder glanced at Meryn and Gendler. Both pretended to look away, but Meryn shot Wilder a wink.

‘Pills, commissar?’ replied Wilder. ‘Yes, I think I might have stumbled on some somnia, just yesterday.’

‘Deary me,’ said Blenner. ‘Well, I had better take that into my safekeeping as soon as possible.’

‘I’ll go and get it for you directly, sir,’ said Wilder.

‘We really should find out where that stuff’s coming from,’ said Meryn idly. ‘Someone could end up with a nasty habit.’

‘That would be unfortunate, captain,’ Blenner agreed.

‘So, the boy?’ Gendler said to Blenner. ‘Gaunt’s son, he paid for this rigmarole?’

‘Yes, Didi,’ said Blenner. ‘Deep pockets, that one, apparently. Rich as feth. Just sent a message to the counting house to access funds.’

‘Did he now?’ echoed Gendler. ‘Well, well.’

Dalin hurried up the stairs to the hab floor where Gaunt’s quarters lay. There was no sign of Gaunt anywhere, and the cortege was waiting.

&nbs

p; There was someone in Gaunt’s office, though. He heard voices through the half-open door, and went to knock.

He paused.

‘Can you do it, Viktor?’ Kolea was asking. ‘Can you authorise it?’

‘It’s highly unorthodox, major,’ Hark replied. ‘I mean, highly. But I seem to have more robust clout with the Munitorum these days. I’ll get on the vox and place the request.’

‘Will Gaunt have to know?’ asked Kolea.

A pause.

‘No, we can keep this between us, for now. It’s rather personal, after all. If anything comes of it, we can decide how we talk to him about it.’

‘Thanks, Viktor.’

‘Come on, Gol. Don’t mention it. I can see how important this is. Do you know, does Vervunhive maintain its own census database, or is it a planetwide list?’

‘Vervunhive has its own census department. I remember them sending the forms out every five years. Births, deaths, marriages. The usual.’

‘And you just want a confirmation of recorded gender?’ asked Hark.

‘Boy or girl, Viktor. That’s all I want to know.’

Dalin froze, his hand reaching for the doorknob.

They knew. They had fething worked it out.

‘What are you hovering there for, trooper?’ said a voice behind him.

Dalin wheeled. It was Major Pasha. There were several men with her. Tall, stern-looking men in cold grey uniforms.

‘S-sorry!’ Dalin stammered.

‘I’m looking for Major Kolea,’ said Pasha. ‘I was told he’d come up here.’

‘He’s inside, I think,’ said Dalin, gesturing to the door.

Pasha knocked and entered.

‘Can I help you, major?’ Hark asked with a smile. His grin faded as he saw the men behind Pasha.

‘These gentlemen, sir,’ said Pasha. ‘They’re looking for Major Kolea. They say they’ve come to fetch him.’

Colonel Grae stepped into the room, flanked by the intelligence service security detail he had brought with him.

‘Major Kolea,’ he said.

‘Colonel Grae,’ Kolea replied.

‘I’m sorry, Kolea,’ said Grae. ‘I need you to come with me.’

‘What the feth is this about?’ asked Hark.

‘Please stand aside, commissar,’ said Grae, showing more composure in the face of an angry Viktor Hark than many would have been able to summon. ‘By order of Astra Militarum intelligence, Major Kolea is under arrest.’

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

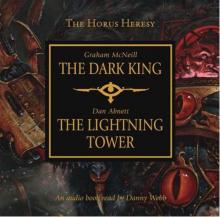

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower