- Home

- Dan Abnett

Ravenor Returned Page 19

Ravenor Returned Read online

Page 19

‘Just calling to see if our employer had answered yet,’ said a voice.

‘Who is this?’ Akunin asked.

‘It’s Siskind. I was just–’

Akunin lowered the communicator and turned to stare at the man sitting opposite him.

‘Siskind’ got to his feet. He seemed to ripple, to shimmer, as if the image of Bartol Siskind was just a reflection in a disturbed pool. Then the ripple stilled itself again and Akunin was staring at a mirror image of himself.

‘Oh Terra,’ Akunin gasped and started to run, dropping his glass and his hand-vox. His double caught up with him before he’d taken three steps, and seized him. Arms pinned, Akunin crashed forward against the sideboard.

‘Please! Please!’ he squealed. The grip constricting him grew tighter.

‘Sire Trice is happy not,’ the double lisped, sliding a long, slim serrated blade out of its cuff.

‘Oh no! Please!’

‘Let him go, Monicker,’ said a voice from the doorway.

‘Akunin’ stepped back and let the real Akunin slump to his knees.

Toros Revoke padded into the room, his stale yellow eyes showing amusement.

‘Get up, Akunin,’ he said.

Trembling, Akunin did as he was told. In all his dealings with the Secretists on behalf of the cartel, Akunin had never found Revoke anything less than terrifying.

‘You seem to have taken it upon yourself to become a nuisance,’ Revoke said. ‘What’s the matter with you, shipmaster? All these pleading demands for a meeting.’

Akunin eyed the secretist warily. ‘I think what I’ve got to say is important.’

‘So… I’m here now. Say it.’

‘Not to you. I need to speak with Trice, a personal meeting–’ Akunin began.

Revoke raised a finger to his lips. ‘First of all, it’s Chief Provost Trice. Second, the remit of Contract Thirteen states clearly that you of the cartel and the chief provost should not be seen together, nor have direct dealings, nor any connection be apparent between such parties. Third, something tried to kill the chief provost the other day. We’ve been a little busy since then trying to discover what it was and who sent it. In comparison, you and your pathetic mewlings are a very, very low priority. ‘

‘I know! Please, I know that! This–’

‘I could have you killed,’ Revoke said bluntly. ‘I could have Monicker here do it. She’s very good.’

Akunin glanced nervously at his double, but it wasn’t his double any more. It was hardly anything. A woman, vaguely, a hazy blur in the air that light seemed to ignore.

‘What is she?’ Akunin asked.

‘Monicker? She’s a dissembler. They’re very rare. It’s a form of albinism, an extreme mutation form. A dissembler’s pigmentation is so shockingly absent, they act as living mirrors, reflecting back likenesses. It’s very useful. Monicker observed your friend Siskind when he visited you earlier today, and mirrored him. Oh, Master Akunin, the look on your face.’

‘You’ve been observing me?’

‘Of course we have,’ Revoke replied. ‘The fuss you’re making. This unseemly frenzy to meet with the chief provost. It’s just not on, Akunin. Not on at all. The provost is furious with you.’

‘Of that, I have no doubt,’ Akunin said, recovering his composure a little. ‘He runs a subsector. I run a ship. I am small fry. I understand that. Me, the other shipmasters under contract, we are just pawns in his great theatre. We do the grunt work, get paid – well paid, I’m under no illusions. We are supposed to get on with our job and be invisible.’

‘Well, you seem to appreciate it quite clearly,’ said Revoke. ‘It begs the question…’

Akunin looked Revoke in the face. ‘I have been insisting on a meeting because I know something that may well be directly connected to the attempt on the chief provost’s life. We have a mutual problem. The entire venture is in jeopardy.’

‘Really? Why?’

‘Gideon Ravenor is still alive. And I have reason to believe he is here on Eustis Majoris.’

Toros Revoke stared at Akunin for a long moment. ‘Do you have proof?’

‘Yes.’

‘Bring it with you. Now.’

Two

It was the third time she’d called that morning. The switchboard put her through, but all she got was an autovox invitation to record a message. For the third time, she didn’t.

The town-hab was quiet, just the ticking of the numerous chrons and horologs her uncle had collected over the years. Maud Plyton paced around the gloomy house, agitated and anxious.

She froze when she heard the music. A sudden, four-finger chord, then a rill and a sprightly refrain. It was coming from the drawing room.

Uncle Valeryn was seated at the spinet, playing one of Steramon’s bagatelles from memory. Plyton stood in the doorway and watched him, her eyes welling up. Every few weeks, her uncle would do this. Like the sun passing out from behind a cloud, his lucidity would briefly return, and he’d play. Then the clouds would return. The patches of lucidity were becoming more infrequent these days.

Valeryn stopped playing. ‘Enid?’ he called. Enid was the private nurse, and she wasn’t due in until three.

‘No, it’s me, Uncle Vally,’ Plyton said, entering the room. ‘Don’t stop playing.’

Valeryn tinkled a few more notes and stopped again. He reached out and took his niece’s hand, squeezing it.

‘Maud. I thought you were Enid,’ he said.

‘No, it’s me,’ Plyton said, knowing her uncle would drift away at any moment.

‘How are things with you?’ he asked.

‘Problems,’ she said.

‘What sort?’ Valeryn replied. ‘Magistratum matters, no doubt?’

She smiled sadly. ‘Yes, Uncle Vally. Department troubles. You don’t want to hear about them.’

‘Don’t I?’ he said, and let go of her hand. He played a series of plangent chords. ‘It’s out of tune,’ he said. ‘There, the upper D, a little flat.’ He struck the note repeatedly. ‘I don’t play this very much now, do I?’

‘Not as much as you used to,’ she said.

Valeryn looked up at her. His face was in shadow. ‘I know, Maud,’ he said.

‘Vally?’

‘I know. Moments like this, I know how I am. Fading. Not always there. There are blanks. These long… intermissions. I don’t remember. It’s very frustrating. I know you’re a Magistratum officer. I know you’ve been living here with me for some time. But I have no idea how old you are or what happened yesterday. I know I have a nurse. Enid, right? So if I have a nurse, I must be ill.’

‘Uncle…’

‘It’s very frustrating. Very frustrating.’ He fell silent. Then he started and looked up at her again. ‘What was I just saying, Enid?’

‘Maud, Uncle Vally. It’s Maud.’

‘Oh, yes. Silly old me. Maud. My, how you’ve grown. How are things with you? Have you got a job, my dear? A man on the go?’

Plyton sighed. ‘Uncle Vally? I’ve got to go out for a while. Enid will be here in another hour or so. Will you be all right?’

‘Enid?’

‘The nurse?’

‘Oh, her. Yes. Yes, I’ll be all right.’

Plyton walked back towards the door, wiping her eyes on her sleeve. The spinet behind her rang out suddenly. A Kronikar valse.

‘Uncle Vally?’

‘I remember,’ he said, without looking round. ‘So much and so little. It’s very hard. The only thing I know for sure is that, when the moments of clarity come, use them. Like now. I don’t know if I’ll ever play again, so I better play now. Use the moment. Seize the moment. You never know how dark it’s going to get otherwise.’

‘Good advice, Uncle Vally,’ she said.

‘I thought so,’ he said. ‘Do what you can, while you still can. Otherwise…’

She looked back. The music had paused.

‘Uncle?’

‘The upper D there. A little flat, w

ouldn’t you say?’ He tapped at it. ‘A little flat, isn’t it, Enid? A little flat?’

‘Yes, Uncle Valeryn,’ Plyton said. She could hear him striking the note over and over as she left the hab and headed for the rail transit.

‘Oh. It’s you,’ said Limbwall, opening the door.

‘Yes. Hello,’ Plyton said. ‘Nice gown there. Are you going to let me in?’

‘What are you doing here?’ Limbwall said, gathering his shabby housecoat around him self-consciously.

‘I rode the transit all the way to E to see you. Can I come in?’

Limbwall hesitated, then reluctantly let her inside his cramped little hab. His face showed the ugly bruises that the fists of the Interior Cases marshals had left on it two days before. He looked scared.

‘What do you want?’ he asked, attempting to tidy up the clutter in his bedsit.

‘Just thought I’d hang out with a work colleague,’ Plyton said.

‘You’ve never hung out with me.’

‘No, I haven’t. Sorry, that was a lie. I wanted to talk to someone.’

‘About what?’ he replied.

She stared at him with ‘What the hell do you think?’ eyes.

Limbwall shrugged. ‘I think you should go, Plyton. I don’t think we’re meant to be speaking to each other. Rickens told us to go back to our habs and wait there to be questioned.’

‘Have you been questioned, Limbwall?’

He shook his head. ‘No, but the Interior Cases investigation wi–’

Plyton scowled. ‘Screw that. Screw them. It shouldn’t work this way.’ She paused. ‘I tried to contact Rickens.’

Limbwall blinked at her, his eyes wide. ‘You did?’

‘Yes. At the department. I don’t have a private contact for him. He’s… unavailable.’ Plyton looked back at him. ‘Since when was Rickens unavailable to his own staff?’

‘Since we all got suspended?’ Limbwall suggested archly.

‘But you’ve got a link. Here. You told me.’

Limbwall sighed. ‘That was a secret.’

‘I know. And they seem to be very popular in the city right now. You told me you’d enhanced your personal cogitator with department codes to keep up with the workload. Limbwall, I think we need to use it. We need to know what’s going on.’

‘I think we should leave it the hell alone,’ he said. ‘That’s what I think. I think if we start meddling, we’ll end up in trouble.’

‘Look what they did to your face, Limbwall. We’re already there.’

‘Start with Rickens. Blanket search.’

Crouched in front of the battered second-hand cogitator set up in the corner of his hab, Limbwall thumped the keys.

‘Service record. Yeah, nothing else. Says he’s on extended leave and directs all enquiries to Interior Cases.’

‘All right, scrub that. The Aulsman Case. Call it up.’ Plyton read out the case file number.

‘There’s no such case listed. Nothing, Plyton.’

‘Not even as closed or restricted?’

‘Seriously, nothing.’

Plyton folded her arms and stared at the floor. ‘I opened the case file myself the day Aulsman’s body was found. All my scene of crime notes, the picts I took. They’ve removed it all and erased the traces.’

‘Magistratum files don’t just get erased,’ he scoffed.

‘Yes, they do,’ she replied. ‘I’ve seen it before.’

‘That’s nonsense,’ he replied, shaking his head. ‘Who has that kind of power?’

Plyton didn’t answer.

‘All right, try the names Whygott and Coober. Marshals, Interior Cases.’

Limbwall chattered the keys and then shook his head. ‘Nothing. No listing on personnel. Were they the two goons who got in your face at the old sacristy?’

‘Yes. Now search for Yrnwood. The limner who witnessed Aulsman’s death.’

Limbwall tapped at his keys.

‘Mmm… nothing. Nothing in Magistratum. Nothing in civic records either. Was it a false ident?’

‘No, he checked out at the time. Run it through the Informium data-core.’

‘I did. There’s nothing.’

‘Holy Throne. They’re hiding everything!’

Limbwall turned to look at her. ‘Who’s “they”, Plyton?’

‘Someone with real power. We’re into subjects of a legitimate investigation, Limbwall. Even Interior Cases isn’t as brazen as this. Last time I saw Rickens, he told me the Aulsman Case was the key. We’d mishandled it somehow, and it was all connected to that assassination attempt on the chief provost. Well, I don’t think we mishandled it at all. I think we found something there in the sacristy, we just didn’t realise what it was.’

‘This… false ceiling you told me about?’

‘Maybe.’ She started buttoning her coat and headed for the door. ‘I’m going home. You pulled me that file on the old city plans. I’ll go and start working through it, see if I can’t find something we’ve missed. You stay here and stay in contact.’

‘Remind me: why are we doing this?’

She grinned. ‘Because we serve at the pleasure of the God-Emperor. And because someone I love very much told me to seize the moment because you never know how dark it’s going to get.’

The sky was turning to a dull undercast as night closed in. Plyton hurried along the pavement as the burn-alarms started to sing and the first spatters of rain started to fall. Too far to run in this. She ducked into the doorway arch of a town-hab to wait out the downpour, just a hundred metres from her uncle’s house.

The rain began to stream down. From the cover of the sinks, the gamper-boys started to yell their trade. She waited. Her mind was ticking over, like one of her uncle’s horologs.

Just a year before. In Rickens’s office. The blanked case. ‘No good will come if it,’ Rickens had told her.

There was a sudden beating of wings. She looked up. A flock of sheen birds swirled up into the rain, turning like a shoal of fish, twisting east.

Something made her very uneasy suddenly.

A sixth sense. What Rickens liked to call the Magistratum muscle.

Ignoring the rain, Plyton ducked out of the archway and ran along the street to the hatchway of the parking garage. She knew her uncle’s code and punched it in. The hatch opened. The attendant, the old man with the apron, waved at her as she walked inside. He knew her. She was the girl who came in to use the Bergman. The attendant wandered away. He was busy soaping up the bodywork of a crimson transporter owned by some local bigwig.

Plyton slipped through the rockcrete gloom, hugging the shadows. Rainwater was gnawing in between the garage’s joints, pooling on the floor in pungent pools. There was the Bergman. Bay A9.

Plyton didn’t have the keys. She peered in through the driver’s door window. There was the folder Limbwall had given her, still tucked into the door pocket. She’d come back for that, once she’d got the keys from Uncle Vally. She walked round behind the automobile, and felt around the dank back wall of the bay for the loose bricks. She kept an eye on the old attendant. He was still washing the crimson transporter.

Plyton lifted three of the soot-black bricks out.

The Tronsvasse 9 was where she’d hidden it, in the cavity, wrapped in vizzy-cloth. She had no permit for the weapon, but every Magistratum marshal owned a back-up piece. It went with the job. Service weapon and a concealed. You never knew when.

Plyton took it out. Heavy, chromed, rubberized grip. Ten in the clip, one in the spout. She eased the slide half-back, saw the glint of the chambered round, and slipped it back. Beside the weapon, two more fat clips.

Plyton put the clips in her pocket, slid the 9 into the waistband of her trousers and put the bricks back.

She waved at the attendant as she walked out of the garage.

The front door of Uncle Valeryn’s town-hab was ajar. Plyton pushed it wide. She could see immediately that something had happened here, something ghastly. It was as if

an erosive force had spilled through the hallway, shredding the wall panels, abrading the carpet, demolishing all the furniture.

Plyton took the Tronsvasse out.

The door to the front parlour was half open. Plyton saw a scattered mess of red-bare bones loosely gathered in a torn blue dress. The shredded remains of a nurse’s starched white headdress. Plyton swallowed hard. Uncle Vally. Uncle Vally.

Weapon braced, she edged along the hall. The place looked as if it had been sandblasted. The wallpaper was stripped, the floorboards scrubbed to bare, splintered wood. The oil paintings on the walls were just empty frames adorned by rags of canvas.

Plyton paused at the doorway of the drawing room and peered in.

Something bony and raw lay on the worn-down carpet in front of the spinet. The spinet itself looked furry. Its once-polished surface was chewed and splintered, the varnished wood pocked with a maelstrom of tiny chips. The curtains were in tatters. Uncle Valeryn’s notation folios were shredded.

A large, slender man was hunched over Uncle Vally’s reduced corpse. Broad-shouldered, with a mane of wispy grey hair, he wore a suit of leather jack with an armoured sleeve.

Drax turned as he heard a sound behind him. His curiously wide face, with its small piggy eyes and a massive underbiting jaw blinked in surprise.

He rose and started to pull out the psyber-lure.

Plyton fired. Her first shot took off the left side of Drax’s face. The second went through his chest and blew out his back. Drax slammed backwards into the ruined spinet, the half-slung lure wrapping around his body. His weight toppled the keyboard instrument over beneath him onto the floor with a discordant clash of strings and keys.

Her eyes burning, Maud Plyton took one last look at her uncle. She backed out of the room. In the litter of debris in the hall, she found fragments of the jar that had always stood on the shelf above the heater. Nearby, she found the Bergman’s keys.

On the pavement outside, running now, she snatched out her hand-vox. ‘Limball? Limbwall! It’s Maud. Get out! Get out now!’

Three

The weapon-servitor reared automatically as Revoke approached. It cycled up its gun-pods and played its pink recog-beam up and down his face. Its handler yanked at its leash and brought it to heel.

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

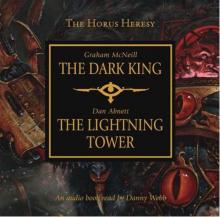

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower