- Home

- Dan Abnett

Penitent Page 15

Penitent Read online

Page 15

‘I know where it is,’ said Renner.

The Shoulder – more properly, The Shoulder Of Orion Amid The Sundry Stars – lay a short walk away, and we went there through busy streets of the quarter. Renner and Kys, in the role of a fine young lady’s bodyguards, walked alert, Kys at my side, and Renner a few paces behind. My cuff, for now, was on, so that Kys would not be encumbered.

‘Why is it you don’t like me?’ I asked Kys as we walked.

‘I never said I didn’t,’ she replied. ‘I tend not to like people much, generally.’

‘No, it is a particular thing,’ I said.

‘I have not met a blank I liked,’ she said. ‘We had one. Frauka. He was odious.’

‘What happened to him?’

‘Long gone,’ she said.

‘So it’s that I am a blacksoul?’

‘And you tried to kill me.’

‘Likewise, but that is behind us. I hold no grudge,’ I said.

‘Nor I,’ she said and looked at me. ‘But your past is a trouble to me. And I believe Gideon’s great weakness is Eisenhorn. You are clearly of Eisenhorn’s part in all this.’

‘He’s dead.’

Kys shrugged. ‘The old bastard’s evaded death many times,’ she said, ‘so I’ll believe it when I see a corpse. And even if he is, his legacy lingers. Those true to his cause, like you. Like Nayl.’

‘You distrust Nayl too?’ I asked. ‘I thought he was an old friend?’

‘He is, but…’ Her voice trailed off.

‘What?’ I asked.

‘Harlon was Eisenhorn’s man for a long time,’ she mused. ‘Then he came to Gideon’s team, like Kara. He’s a good man, I’ll grant you, a good fighter. But he is getting old. Slow. Not the force he was. We are friends, I suppose.’

‘But?’

‘When Eisenhorn reappeared, Nayl went back to him. I dislike those who can switch masters so easily.’

‘Kara–’

‘Kara didn’t go back,’ Kys said. ‘Once she had stood with Gideon, there she stayed. And I have been with Gideon since my start. But not Harlon. He’s a strong brute, but to flip back and forth… That speaks of a weak character.’

‘Or a torn one,’ I countered. ‘I think he’s loyal to them both, but their rivalry has put him in an impossible place. And he’s only come back now because of circumstance. Might I suggest, in all reason, that Nayl serves one true master… Not Gregor or Gideon, but the Throne itself?’

Kys snorted.

‘He’s a sell-sword, you silly girl,’ she said. ‘Besides, I only care to trust what I know. Not some faraway concept. I’ll trust only those I can look in the eye.’

‘And how do you look Ravenor in the eye?’ I asked.

She scowled.

‘You are new to this, Bequin,’ she said. ‘You have not walked the dark places as we have. You have not learned that trust is earned through adversity. Only yesterday, you stood four-square with the Cognitae.’

‘I would not have, had I known,’ I said. ‘But it’s odd. I am told we are much alike, you and me. Both orphans, born with outcast gifts, raised in cruel scholams–’

‘Kara had no right to tell you such things.’

‘It wasn’t Kara,’ I replied. ‘It was Harlon. He spoke of you when we first met, when we both believed I had killed you at the Maze Undue. He mourned you, Patience. Your friendship towards him may be cool these days, but his respect and affection for you remains strong.’

She made no answer.

‘Be reassured–’ I pressed.

‘There’s nothing reassuring about this work,’ Kys said. ‘You’re all under the influence of the great Gregor Eisenhorn – you, Nayl, Kara, even Gideon. You’re all in awe of him. I’m not. I’m the one thing that will keep you true.’

The Shoulder was a sprawling tavern, much lit with glow-globes and hanging lamps. It was crowded too, but we could hear Crookley’s guffaws even as we entered.

He was holding court with his coterie in a private side parlour, some twenty people in all, and many I did not recognise, but they were surely the usual strays and hangers-on that his notoriety, and Aulay’s purse, attached to him of an evening. They enjoyed the frisson of being a temporary friend of the infamous poet, and the transgressive thrill that they might become party to some discussion of forbidden occult mysteries, but most of all they liked the fact that someone else was paying for their night out. The table was piled with the remains of a hearty dinner, and serving girls were running in with fresh bottles.

‘Mamzel Flyde!’ Crookley boomed the moment he saw me in the doorway. He was already half-cut, his mouth greasy from the haunch of gannek he had but recently devoured. ‘You are too long from our company! We have missed you!’

He came to me at once, to kiss me upon the cheeks, a greeting that I was spared by the figure of Kys, who interposed herself and stared down Crookley with no little disdain.

‘And, who,’ exclaimed Crookley, not at all put out, and his eyes fair straining as he took in Kys, ‘is this delightful creature?’

‘This is Patience, Oztin,’ I replied. ‘She is one of my lifewards. I fear my husband is away on business, and he insists that I not go abroad in society without some safeguard. It is, I think, unseemly for a young married lady to step out without proper escort.’

‘Quite right,’ said Crookley. ‘Quite apart from propriety, one might encounter the most unsavoury types in these benighted streets.’

He turned to Kys, who, as I had expected, had captivated him at once. That she was beautiful I had no doubt, but it was the menace in her that I knew would matter more. Pretty girls were ten a penny to the likes of Crookley, but a sense of danger and the prospect of a true challenge quite entranced a man of his transgressive character. He immediately offered her a glass of amasec, insisted she took the seat beside him, and plied her with questions: where had she trained? How many arts of killing did she know? Could she kill with her bare hands? How many men had she done away with? All the while, his gaze was fixed upon her face. I fancied he thought he was beguiling her, or mesmerising her with some weird gift he believed he possessed, taught to him by the spirits of the air. He was, after all, a magus, empowered with dark cunnings and esoteric tricks of sex and magic.

Kys played along, of course. Crookley was no direct use to me, for he talked much, especially in his cups, and said nothing of merit or truth. He had to be distracted and occupied while I went to work.

The room was busy, with much laughter and chatter. I spotted Aulay, but knew he was of no particular use, for he was very drunk as ever, and never spoke much to begin with. I pushed through several of the guests, and located the stern Academy tutor, Mam Matichek.

‘My dear,’ she said, and pecked my cheek. ‘Have a seat with me. Oztin says he is to recite his new odes tonight, so there is much excitement, though I doubt the grammar will be any better than last time. And your girl, it seems, has delayed him further.’

She nodded meaningfully across the busy table, to where Crookley was gazing into Patience’s eyes while she answered his incessant questions in a fashion that was, I was sure, both brutally glib and seductively mysterious.

‘You come alone?’ enquired Mam Matichek.

‘Daesum is away,’ I said.

‘On business?’

‘It can’t be helped.’

‘And he lends you lifewards?’

‘I can hardly look after myself in the streets of Feygate,’ I replied. She shot me a look that suggested, just for a second, that she believed quite the opposite.

‘The woman I get,’ she remarked, ‘a high-class ’ward. Sunderer Martial School? Or Wayfarer’s Agency?’

‘Kresper House,’ I said.

‘Oh, the very best service. Which makes the other even odder. A Curst?’

Renner was lingering by the d

oor, his eyes on me.

‘Indeed, yes,’ I said. ‘Daesum is rather funny. He believes that burdeners make for the best guardians, because of their sworn duty. He takes them into service. I am rather obliged to accept my husband’s notions. That man has almost become part of the household.’

‘What’s his name?’ she asked.

‘Why,’ I said, answering as Violetta would, ‘I have no idea at all. We call him “Curst”, and he answers.’

Mam Matichek poured me a flute of joiliq. Through my function, I was presenting to her exactly the person she assumed I was: a wealthy, bored, privileged young gentlewoman, amusing herself by slumming with rakish intellectuals and would-be illuminates of ‘secret lore’.

‘I see very few of the faces from last time,’ I remarked.

‘Such as?’

‘I was quite taken by Mr Dance,’ I said.

‘And he with you,’ she replied. ‘I hear you set him a mathematical test.’

‘Oh, nothing so formal,’ I replied. ‘We were talking of numbers, and I asked the implications of one.’

‘And we have not seen him since,’ said Mam Matichek. ‘According to Unvence, our Freddy has been locked away, night and day, quite obsessed.’

‘I am sorry to hear it,’ I replied. ‘I had not meant to set him fast on some task.’

‘Sadly,’ she said, ‘that is his way. His mind is fragile. Poor Freddy. He has a habit of seizing on something and fetishising it. Obsession is the right word, quite compulsive. Unvence says Freddy can’t be torn away from his books, not even for the promise of liquor, and has almost forgotten to eat or bathe. I confess, my dear Mam Flyde, I am quite glad to see you tonight. I was hoping I might ask a favour.’

‘Ask,’ I said.

‘I was wondering if you might come, perhaps tomorrow, and call upon Freddy with me? Unvence can arrange it. You see, I think if you visited him, and listened to his findings for a quarter-hour, and expressed satisfaction, he might cease this current bout of obsession, or at least be eased of his burden. He may ease back if he thinks he has satisfactorily resolved an issue raised by a pretty young lady. I do fear for his health.’

‘I would be glad to do it,’ I said. ‘I am most sorry to hear I have derailed him with such a trivial matter.’

‘At four tomorrow, then,’ she said. ‘In the courtyard of the Academy. You know it, I suppose?’

‘I do. I will meet you there.’

‘That’s very kind,’ she replied, and took a small silver case from her black crepe purse. She handed me a neatly embossed calling card. ‘But I appreciate you are a very busy young lady. If you are unable to make the appointment, send word to me, and we will rearrange.’

Not long after that, Renner came to me, and drew me to one side. The rowdy merrymaking in the parlour continued, and was so loud, he had to lean close to my ear and whisper.

‘I have seen him,’ he said.

‘Seen who?’

‘The man. The musician,’ he replied. ‘Connort Timurlin, the one you said you wished to find.’

‘Where?’

‘Why, out in the main saloon, playing on the clavier.’

We stepped out of the private room. I cast a nod to Kys, letting her know I would not be long, and that she should stay put and occupy Crookley.

There was a narrow serving hall between the parlour and the main saloon. It was chilly there, and harried-looking serving staff bustled past us. From the saloon beyond, I could hear the fine playing of a keyboard above the noise of the bar. The Milankovich Variations in A.

I paused, and looked at Renner Lightburn.

‘What?’ he asked.

‘How did you know?’ I asked.

‘Know what?’

‘You say you saw him, but you’ve never seen him, not to know his face.’

He shrugged.

‘The inquisitor put it there,’ he replied, tapping his forehead. ‘He’d seen the faces from your memories, and he shared it with all of us so we’d know who to look for. Timurlin, the Dance chap, and all the rest of note in this crowd. Their faces all popped up. Fair creepy, it was. I little like these psykana doings.’

He looked at me, and noticed my mood.

‘Did he not tell you?’ he asked.

Ravenor had not told me. It was not an abuse of trust, exactly, and it made great sense in terms of the efficiency of our work. I imagined it was standard practice for his warband: he would routinely copy visual information from one mind to another, so that all could be aware. But I couldn’t help but feel as if he had cheated me, somehow. I had let him into my mind and stood with him, so to speak, as he politely looked around. Now he was sharing my thoughts with others, without permission. I wondered what else of me he had shared. I wondered what else he might have taken without my knowing.

I reminded myself that this was probably habit, and simply an everyday thing for so potent a psyker and the people he worked with. I imagined Ravenor might be mortified to realise my offence at the casual intrusion, and apologise most genuinely.

But it rankled, and weakened my trust in him, a trust that was not yet strongly grown.

‘Stay back and shadow me,’ I told Renner.

I pushed through the padded swing doors into The Shoulder’s main public saloon. It was warm and well lit, very busy, and the air stank of lho smoke and spilled liquor. Small tables stood to one side, where hot suppers were still being served. The night crowd was packed four deep at the long bar, and most other bar-tables and booths were filled.

At the far end, beyond the bar, an old clavier stood before the alcove that led to the cellars. Timurlin was sitting at it, playing, amusing a small crowd who were paying for his amasecs. The music was fine, despite the odd dull notes of the old instrument’s raddled keys.

When I arrived at his side, he glanced up quickly with a smile, expecting to see another admirer, then did a double take and stopped playing.

‘Mamzel!’ he said.

‘Mr Timurlin,’ I said, smiling. ‘When I heard the music, I knew it could only be you. The Connort Timurlin.’

He got up, and bowed.

‘Please, don’t let me interrupt,’ I said.

‘I’m just playing for fun,’ he said with a smile. I could sense he was nervous.

‘And for modest payment,’ I said, and helped myself to one of the amasecs his audience had lined up along the top of the clavier’s case. ‘I was looking for you,’ I said, taking a sip and keeping my stare fixed on him.

‘Why, whatever for?’ he asked. His body language was off. It was more than nerves, or surprise. He was wearing a green hanymet suit and half-cape of quality. I studied him for concealed weapons, and detected none.

‘I was meaning to ask you,’ I said, ‘and I quite forgot last time we met. How is Zoya?’

‘Zoya?’

I nodded. ‘How is she?’

A change settled upon his face. A hard look, the look of a man who is unexpectedly caught out and cornered.

‘I don’t know any Zo–’

I raised one finger to hush him, knocked back the amasec, and set the empty glass down. My eyes did not leave his.

‘Please don’t,’ I said. ‘I’m in no mood for a game of pretend. We both know you know Zoya. How is she?’

‘Why do you ask?’ he said, apprehensive.

‘Mam Tontelle sends her regards,’ I said.

At that, he snapped, and made to kill me.

CHAPTER 16

Which is of pursuit

He swung his fist at my head.

It seemed the wild thrash of a desperate man, but it was not impulsive. I had fought, and been schooled in fighting, enough to read the blow, and the fact that it was not telegraphed. There was no microexpression of warning, of prior tension or bracing. It just came, expert and fluid. Just as fast, I dip

ped down to avoid it. But even as I did so, I was puzzled, for it was not a blow that anyone would strike with the hand, especially not a man who was clearly proficient. The move was more a sword-stroke, aimed at the side of my neck. Why strike so, with a fist?

All this I relate now in a hundred, perhaps a thousand, times the instant it took for the blow to come. It was fast, and I barely avoided it.

And in avoiding it, I found my answer.

A sword’s blade missed my head and buried itself in the side of the old clavier. It buried itself deep. The impact shook the instrument, and knocked over the glasses of amasec standing along its top.

There had not been a sword in his hand a half-second before. There had not been a place for him to conceal a sword. It had just appeared in his grip.

I knew what it was, and thus knew what he was.

I could do nothing but throw myself aside as he ripped the blade out of the wood case, and sliced at me again. I had to spin to avoid, and then sidestep to dodge the murderous third strike. The sword – a straight cutro with a metre-long blade – cut through the silks and lace of my skirts and underskirts. The crowd cried out, backed away, some dropping the glasses they were holding. I darted aside again, and the tip of the chasing blade punched through the back of an empty chair. He was driving straight at me, and without ability to parry, I had to create space. I grabbed the rim of a small round table, and threw the whole thing at him, the drinks upon it and all. Timurlin staggered back against the clavier. The table had bought me a second, time to cross my arms and unfasten my slucas from their forearm sheaths. As Timurlin re-addressed, I threw my arms wide, gravity sliding the knives out of my sleeves and into my hands. I deflected his thrust with the blade in my right hand.

Timurlin was relentless. He had committed to murder, and would not back off, even now his target was armed. He hammered thrusts and slices at me with expert skill and dizzying speed. Now I closed, cutting down the distance between us, and endeavouring to both command the space, and control his blade. I parried, with one blade or the other, or both crossed in a V, or else danced out of his line as best as Violetta’s gown would allow.

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

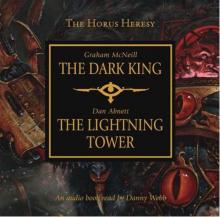

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower