- Home

- Dan Abnett

THE WARMASTER Page 13

THE WARMASTER Read online

Page 13

Sindre looked at him with considerable distaste.

‘Storm troop,’ Sindre called out. ‘Take possession of the prisoner and prepare to move. Double file guard. Watch his every move.’

The Urdeshi storm troopers moved forwards.

‘S Company, Tanith First,’ said Sindre, ‘you are relieved of duty. Your vigilance and effort is appreciated.’

‘We stand relieved,’ replied Rawne.

The Urdeshi moved Mabbon towards the hatch. It was slow going because his stride was so abbreviated by the shackles.

‘Hey!’

They paused, and Sindre looked back. Varl had gone into the etogaur’s cell and reappeared holding a sheaf of cheap, tatty pamphlets and chapbooks.

‘These belong to him,’ he said, holding them out.

Interrogator Sindre took the pamphlets and flicked through them.

‘Trancemissionary texts,’ he mused, ‘and a copy of The Spheres of Longing.’

‘He reads them,’ said Varl.

Sindre handed them back.

‘No reading material is permitted,’ he said.

‘But they belong to him.’

‘Nothing belongs to him, trooper,’ said Sindre. ‘No rights, no possessions. And besides, he will have no need for reading matter. He will be… busy talking.’

Varl glanced at Rawne, and Rawne quietly shook his head. At the hatch, surrounded by the impassive storm troopers, Mabbon looked back over his shoulder and nodded very slightly to Varl.

‘You… you watch him,’ said Varl. ‘He’s a sly one, that pheguth.’

‘You take care of yourself, Sergeant Varl,’ said Mabbon. ‘We won’t meet again.’

‘You never know,’ said Varl.

‘I think I do,’ said Mabbon.

‘That’s enough. No talking,’ Sindre snapped at Mabbon. ‘Move.’

The storm troopers led him away.

Luna Fazekiel led Baskevyl and Kolea to the hatch of hold ninety.

‘Our visitors,’ she remarked sidelong.

A man in the plain, dark uniform of the Astra Militarum intelligence service was waiting for them, accompanied by a cowled representative of the Adeptus Mechanicus and a tall woman in a long storm coat who could only be from the ordos. A gang of Mechanicus servitors and several other aides and assistants waited in the corridor behind them, as well as intelligence service soldiers with plasma weapons. Elam, and a squad from his company, blocked them from the hatch door.

‘Ma’am,’ said Elam as the trio approached.

‘Are you in charge here?’ the intelligence officer asked Fazekiel. He was well made and handsome, with thick, dark hair, cut close, and greying at the temples.

‘We have been kept waiting,’ said the female inquisitor. ‘You have the authority to open this hold?’

As they had approached, Kolea had been struck by the woman’s appearance. She was tall and slender, and her head, with its shaved scalp, had the most feline, high-cheekboned profile he had seen on a human. She possessed the sort of attenuated, sculptural beauty he imagined of the fabled aeldari.

But as she turned to regard them, he saw it was reconstruction work. The entire upper part of her head that had been facing away from them was gone, from the philtrum up, replaced by intricate silver and gold augmetics, fashioned like some master-crafted weapon. Her mouth was real, and her eyes, presumably also real, gleamed in the complex golden sockets of her face. She had been rebuilt, and the surgeons and augmeticists had only been able to save the lower part of her face. Even that, Kolea fancied, was just a careful copy of what had once existed. The augmetic portion had obviously been destroyed beyond hope of reconstruction. It shocked him, and fascinated him. He was alarmed to realise that he almost found the intricate golden workings of her visage more beautiful than the perfect skin of her jaw.

‘My apologies,’ said Fazekiel. ‘Disembarkation after a long journey is a demanding process. We have authority to break the seals. I am Commissar Fazekiel. This is Major Kolea, and Major Baskevyl.’

‘Colonel Grae,’ said the intelligence officer. ‘With me, Versenginseer Lohl Etruin of the Adeptus Mechanicus and Sheeva Laksheema of the Ordo Xenos.’

The cowled adept twitched an actuator wand, and a small, plump woman stepped forwards from the entourage. She wore a simple robe and tabard, and her hair was tight curls of silver. She presented Fazekiel with a thick sheaf of papers.

‘Documentation for the receiver party,’ she said, looking up at Fazekiel. ‘It lists and accredits all personnel present, including the servitor crew and the savants.’

‘You are?’ asked Fazekiel.

‘My lead savant, Onabel,’ said Laksheema, ‘and her identity is not pertinent to this discussion. Please explain, I am concerned that the hold seal has been tampered with.’

‘We ran into trouble, ma’am,’ said Kolea.

‘The ship was boarded. We fought them off,’ said Fazekiel. ‘However, we were obliged to open and search all the ship compartments to ensure that no agents of the foe remained in hiding.’

‘Who opened it?’ asked Laksheema.

‘I did,’ said Baskevyl. ‘It was opened on my command.’

The cowled adept made a small, clicking, buzzing sound. Laksheema nodded.

‘I agree, Etriun,’ she said. She looked at Baskevyl. ‘Operational orders stated that the material recovered from Salvation’s Reach should remain sealed for the return voyage. There is potential danger and hazard to the untrained and uninformed.’

‘Operational orders that are now over ten years old,’ said Kolea.

‘As my colleague explained, ma’am,’ said Baskevyl, ‘circumstances changed. I thought it better to risk the potential hazard rather than risk even greater danger. A field decision.’

Laksheema stared at him. ‘A field decision,’ she said. ‘How very Astra Militarum. You are Baskevyl?’

‘Major Braden Baskevyl, Tanith First, ma’am.’

‘But you are Belladon born.’

‘My insignia gives me away,’ he replied, lightly.

‘No, your accent. When you opened the hold, Baskevyl, what did you find?’

‘Disruption to the cargo. Some contents shifted and spilled. I checked the area for signs of intruders, found none, and so immediately resealed the hold.’

‘Because?’ Laksheema asked.

‘Operational orders, ma’am,’ said Baskevyl.

‘No,’ she said. ‘Something else. I see it in your manner.’

Baskevyl glanced at Kolea.

‘One of the crates had spilled in a way I could not explain. Our asset had suggested that this particular set of items constitute perhaps the most valuable artefacts recovered during the raid. I touched nothing. I left them where they were and resealed the hold.’

The adept buzzed and warbled quietly again.

‘Indeed,’ Laksheema nodded. ‘Define “in a way I could not explain”, please, major.’

‘The crate contained stone tiles or tablets, ma’am,’ said Baskevyl, uncomfortably. ‘They had fallen, but arranged themselves in rows.’

‘Rows?’ echoed Grae.

Baskevyl gestured, to explain.

‘Perfect rows, sir,’ he said. ‘Perfectly aligned. It seemed to me very unlikely that they could just land like that.’

‘And you left them?’ asked Laksheema.

‘Yes.’

‘How did it make you feel?’ asked the stocky little savant.

‘Feel?’ replied Baskevyl. ‘I… I don’t know… My inclination was to pick them up, but I felt that was unwise.’

‘Anything else of note occur during the voyage?’ asked Grae.

‘Plenty,’ said Kolea. ‘It was a busy trip.’

‘That you’d like to relate, I mean,’ said Grae.

Baskevyl glanced at Kolea. Neither wanted to be the one to open the can of worms about the eagle stones and the voice. Besides, it was above their grade now, and part of the official mission report document.

‘T

here is a great deal you are not telling us, isn’t there?’ asked the inquisitor.

‘The mission report is long, complex and classified,’ said Baskevyl.

‘The details can’t circulate until the report has been presented to high command and the warmaster, and validated by them,’ said Kolea.

‘And the ordos do not warrant inclusion in that list?’ asked Laksheema.

‘It’s a matter of Militarum protocol–’ Baskevyl began.

‘Shall I tell you what I think of protocol?’ asked the inquisitor.

‘Our commanding officer is on his way right now to deliver the full report to staff,’ said Fazekiel quickly. ‘He’s presenting it in person. The details were considered too sensitive to commit to signal or other form that could be intercepted.’

‘This is… Gaunt?’ asked Laksheema.

‘Yes, ma’am.’

‘His reputation precedes him,’ remarked Grae.

‘Does it, sir?’ asked Kolea.

‘It does, major,’ said the intelligence officer. ‘Amplified considerably by death, which of course now proves to be incorrect. He has made quite a name for himself, posthumously. It is rare a man turns up alive to appreciate that.’

‘I’m sure the colonel-commissar will deliver the report in full to you too,’ said Fazekiel.

‘Of course he will,’ said Laksheema. ‘The warmaster has drawn up our working group to examine and identify the materials gathered. Full accounts must be collated from all involved, and all who had contact, as well as a detailed consideration of any events surrounding the mission that may be relevant.’

She looked at Kolea.

‘Even those which may not appear to the layman to be relevant,’ she added.

‘We will need full lists of everyone who had any contact with the items during recovery and storage,’ said Grae. ‘Anyone who was… exposed.’

Kolea nodded. ‘That’s quite a large number of personnel, sir.’

‘They will all be interviewed,’ said Grae.

The adept whirred.

‘Etruin asks who collated and indexed the material for the manifest.’

‘I did,’ said Fazekiel.

Laksheema nodded.

‘The manifest is very thorough. You have a keen preoccupation with detail, Commissar Fazekiel.’

‘I imagine that’s why Gaunt charged me with the duty, ma’am,’ Fazekiel replied.

‘You are methodical,’ Laksheema mused. ‘Obsessive compulsive. Has the condition been diagnosed and peer-reviewed?’

‘Has it… what?’ asked Fazekiel.

‘Shall we open the hatch?’ suggested Baskevyl. ‘You can take charge of it. We’ll be glad to see the back of this stuff.’

I know I will, thought Kolea.

A long column of cargo-8 trucks left the staging gates of plating dock eight and followed the old streets down the hill into Eltath. The rain had stopped, and the skies were puzzle-grey. Rainwater had collected in the potholes and ruts pitting the rockcrete roads, and the big wheels of the passing trucks sprayed it up in sheets.

The buildings of the quarter were old, and looked derelict. They had once been the headquarters and storehouses of merchants and shipping guilds, but war had emptied them long before, and they stood silent and often boarded. Time and weather had robbed some of roof tiles, and in places, there were vacant lots where the neighbouring buildings were propped with girder braces to prevent them slumping sideways into the mounds of rubble. The rubble was overgrown with lichen and creeper weeds. These were the sites of buildings lost to shelling and air raids. The spaces they left in the street frontages were like gaps in a row of teeth.

The motor column was carrying the first of the Tanith to their assigned billets. Tona Criid rode in the cab of the lead vehicle. She peered at the dismal buildings as they rumbled past.

‘When did the war here end?’ she asked.

‘The war hasn’t ended,’ replied the Urdeshi pool driver.

‘No, I mean the last war?’

‘Which last war?’ he asked, unhelpfully. He glanced at her. ‘Urdesh has been at war for decades. Conquest, occupation, liberation, reconquest. The whole system, contested since forever. One war followed by another, followed by another.’

‘But you endure?’ she asked.

‘What choice have we got? This is our world.’

Criid thought about that.

‘Forgive me for asking,’ said the driver after a while, his eyes on the road, ‘you’ve come here to fight, and you don’t know what the war is?’

‘That’s fairly normal,’ said Criid. ‘We just go where we’re sent, and we fight. Anyway, it’s the same war. The same war, everywhere.’

‘True, I suppose,’ the man replied.

They drove further through the old quarter. The streets were as lifeless as before. Criid began to notice material strung across the streets from building to building, like processional bunting. But it was sheets, carpets, old faded curtains, and other large stretches of canvas that hung limply in the damp air. The sheets hung so low in places, they brushed the tops of the moving trucks.

‘What’s that about?’ she asked, gesturing to the sheets.

‘Snipers,’ said the driver.

‘Snipers?’

‘We string the streets up with cloth like that to reduce any line of sight,’ the driver said. ‘It blocks the scoping opportunities for marksmen.’

‘There are snipers here?’ asked Criid.

‘From time to time,’ the man nodded. ‘The Archenemy is everywhere. Not so much here these days. The main fighting is in the south and the east. Those are whole different kinds of kill-zones. But the enemy sneaks in sometimes. Insurgents, suicide packs, infiltration units, sometimes bastards who have laid low in the bomb-wastes or the sewers since the last occupation. They like to cause trouble.’

Criid nodded. ‘Good to know,’ she said.

He glanced at her again.

‘Learn the habits now you’re here,’ he said. ‘Stay away from windows. Don’t loiter outdoors. And watch out for garbage or debris in roads or doorways. Derelict vehicles too. The bastards like to leave surprises around. Seldom a day goes past without a bomb.’

They reached a junction, and ground to a halt, waiting as heavy cargo transporters and armoured cars growled by, heading towards the docks.

Across the junction, Criid saw the end wall of an old manufactory. Someone, with some skill, had taken paint to it and daubed the words ‘THE SAINT LIVES AND IS WITH US’ in huge red letters. Beside it was a crude but expressive image of a woman with a sword.

‘The Saint,’ said Criid.

‘Beati Sabbat, may she bless us and watch over us,’ said the driver.

‘Good to see that Urdesh is strong in faith at least,’ she said.

‘Not just a matter of faith,’ said the driver, putting the cargo-8 in gear and leading the convoy away again onto a long slope towards the garment district. ‘She’s here. Here with us.’

‘The Saint?’

‘Yes, lady.’

‘Saint Sabbat is here on Urdesh?’ she asked.

‘Yes,’ said the driver. ‘Didn’t they tell you anything?’

THIRTEEN: GOOD FAITH

The Urdeshic Palace occupied the cone of the Great Hill. Eltath was the subcontinental capital of the Northern Dynastic Clave, and like all of Urdesh’s forge cities, its situation and importance were determined by the geothermal power of the volcanic outcrop. The Adeptus Mechanicus had come to Urdesh thousands of years before, during the early settlement of the Sabbat Worlds, and capped and tamed the world’s vulcan cones to heat and power their industries. Urdesh was not just strategically significant because of its location: it was a vital, living asset to mass manufacture.

Van Voytz’s transport, under heavy escort, moved up through the hillside thoroughfares, passing the towers of the Mechanicus manufactories and vapour mills that plugged the slopes and drew power from the geothermal reserves. Swathes of steam and smok

e clad the upper parts of the city, hanging like mountain weather, the by-product of industry. Soot and grime caked the work towers and construction halls, and blackened the great icons of the Machine-God that badged the manufactory walls.

‘At one time,’ Van Voytz remarked, ‘they say the Mechanicus employed as many work crews to maintain the forge palaces as they did in the forges themselves. They’d clean and re-clean, never-ending toil, to keep those emblems blazing gold and polish the white stones of the walls. But this is wartime, Bram. Looks are less important, and the Mechanicus needs all its manpower at work inside. So the dirt builds up, and the glory fades.’

‘I’m sure there is some parable there, sir,’ ventured Biota, ‘of Urdesh itself. The endless toil to keep it free from ruinous filth.’

Van Voytz smiled.

‘I’m sure, my old friend. The unbowed pride of the Urdeshi Dynasts, labouring forever. I’m sure the adepts have composed code-songs about it.’

‘She’s really here?’ asked Gaunt.

Van Voytz looked amused, seeing how distractedly Gaunt stared from the transport’s window at the city moving past.

‘She is, Bram,’ he said.

‘Sanian? From Hagia?’

‘She hasn’t used that name in a long time,’ said Van Voytz. ‘She is the Beati now, in all measure, a figurehead for our monumental struggle.’

Gaunt looked at the general.

‘Can I see her?’ he asked.

Van Voytz shook his head.

‘No, Bram. Not for a while at least.’

‘It is a matter of logistics,’ put in Biota helpfully. ‘She is placed with the Ghereppan campaign, in the southern hemisphere, many thousands of kilometres from here, where the fighting is most intense. Access is difficult. Perhaps a vox-link might be established for you.’

‘How long has she been here?’ Gaunt asked.

‘Since the counter-strike began,’ said Van Voytz. ‘So… four years?’

‘Three,’ said Biota. ‘Colonel-commissar, many aspects of the campaign have changed since you… since you were last privy to the situation. I should brief you on the details as early as possible.’

Saturnine

Saturnine The Magos

The Magos Penitent

Penitent THE WARMASTER

THE WARMASTER Gilead's Blood

Gilead's Blood Sabbat Crusade

Sabbat Crusade![[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[warhammer_40k]_-_double_eagle_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle

[Warhammer 40K] - Double Eagle![[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_02]_-_ghostmaker_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker

[Gaunt's Ghosts 02] - Ghostmaker![[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_10]_-_the_armour_of_contempt_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt

[Gaunt's Ghosts 10] - The Armour of Contempt Ravenor

Ravenor Border Princes

Border Princes Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 02 - Malleus (Abnett, Dan) Eisenhorn Omnibus

Eisenhorn Omnibus Prospero Burns

Prospero Burns The Story of Martha

The Story of Martha Extinction Event

Extinction Event Playing Patience

Playing Patience Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever

Lara Croft and the Blade of Gwynnever Regia Occulta

Regia Occulta![[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[gaunts_ghosts]_-_the_iron_star_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star

[Gaunt's Ghosts] - The Iron Star![[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/13/[warhammer]_-_fell_cargo_preview.jpg) [Warhammer] - Fell Cargo

[Warhammer] - Fell Cargo GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: ROCKET RACCOON & GROOT STEAL THE GALAXY!![[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_01]_ravenor_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 01] Ravenor - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[gaunts_ghosts_06]_-_straight_silver_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver

[Gaunt's Ghosts 06] - Straight Silver![[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/[ravenor_02]_ravenor_returned_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 02] Ravenor Returned - Dan Abnett![[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/14/[gaunts_ghosts_08]_-_traitor_general_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General

[Gaunt's Ghosts 08] - Traitor General The Unremembered Empire

The Unremembered Empire First and Only

First and Only![[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/15/[darkblade_05]_-_lord_of_ruin_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin

[Darkblade 05] - Lord of Ruin Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 01 - Xenos (Abnett, Dan) Meduson

Meduson The Fall of Malvolion

The Fall of Malvolion Dragon Frontier

Dragon Frontier Sabbat Worlds

Sabbat Worlds Horus Rising

Horus Rising Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword

Warhammer - Darkblade 04 - Warpsword Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose

Avengers_Everybody Wants to Rule the World_Marvel Comics Prose![[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_04]_-_honour_guard_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard

[Gaunt's Ghosts 04] - Honour Guard![[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_04]_-_warpsword_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 04] - Warpsword

[Darkblade 04] - Warpsword![[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[gaunts_ghosts_11]_-_only_in_death_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death

[Gaunt's Ghosts 11] - Only in Death Ravenor Rogue

Ravenor Rogue![[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[ravenor_03]_ravenor_rogue_-_dan_abnett_preview.jpg) [Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett

[Ravenor 03] Ravenor Rogue - Dan Abnett Double Eagle

Double Eagle Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By

Doctor Who - The Silent Stars Go By Brothers of the Snake

Brothers of the Snake Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)

Warhammer - Eisenhorn 03 - Hereticus (Abnett, Dan)![[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/[darkblade_03]_-_reaper_of_souls_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls

[Darkblade 03] - Reaper of Souls Thorn Wishes Talon

Thorn Wishes Talon Doctor Who

Doctor Who Ravenor Returned

Ravenor Returned Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Embedded

Embedded Salvation's Reach

Salvation's Reach![[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/[gaunts_ghosts_03]_-_necropolis_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis

[Gaunt's Ghosts 03] - Necropolis![[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[darkblade_01]_-_the_daemons_curse_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse

[Darkblade 01] - The Daemon's Curse Know No Fear

Know No Fear Dan Abnett - Embedded

Dan Abnett - Embedded 00.1 - The Blood Price

00.1 - The Blood Price![[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/17/[warhammer_40k]_-_sabbat_worlds_preview.jpg) [Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds

[Warhammer 40K] - Sabbat Worlds Necropolis

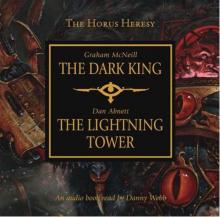

Necropolis The Lightning Tower & The Dark King

The Lightning Tower & The Dark King Legion

Legion Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals

Tomb Raider: The Ten Thousand Immortals Avengers

Avengers I am Slaughter

I am Slaughter![[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_07]_-_sabbat_martyr_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr

[Gaunt's Ghosts 07] - Sabbat Martyr The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising

The Horus Heresy: Horus Rising![[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_01]_-_first_&_only_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only

[Gaunt's Ghosts 01] - First & Only Ravenor Omnibus

Ravenor Omnibus Ghostmaker

Ghostmaker Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor

Pariah: Eisenhorn vs Ravenor![[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/04/[gaunts_ghosts_12]_-_blood_pact_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact

[Gaunt's Ghosts 12] - Blood Pact![[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/[gaunts_ghosts_05]_-_the_guns_of_tanith_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith

[Gaunt's Ghosts 05] - The Guns of Tanith Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero

Triumff: Her Majesty's Hero![[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/[gaunts_ghosts_09]_-_his_last_command_preview.jpg) [Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command

[Gaunt's Ghosts 09] - His Last Command![[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/03/[darkblade_00_1]_-_the_blood_price_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price

[Darkblade 00.1] - The Blood Price Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy!

Guardians of the Galaxy: Rocket Raccoon and Groot - Steal the Galaxy! Vermilion Level

Vermilion Level In Remembrance

In Remembrance The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

The Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World Border Princes t-2

Border Princes t-2![[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/darkblade_02_-_bloodstorm_preview.jpg) [Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm

[Darkblade 02] - Bloodstorm Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19

Know no fear. The Battle of Calth hh-19 The Dark King and The Lightning Tower

The Dark King and The Lightning Tower